By Yasuaki Mitsuwa

Director Yoshinari Nishikôri and Cinematographer Akira Sako, JSC recently completed the feature Tatara Samurai. This interview took place at the Imagica head office in Tokyo after the first screening of the film in April.

Cinematographer Akira Sako, JSC (L) and Director Yoshinari Nishikôri (R)

FILM AND DIGITAL TIMES JAPAN (FDTJ):

Tell us about the film Tatara Samurai.

DIRECTOR YOSHINARI NISHIKÔRI (N): “Tatara” is a unique steelmaking method that uses a foot-operated bellows to forge Japanese swords. The process, which is called “Tatara-buki,” has been employed for 1,000 years. I wanted to make a film about Tatara and it came true. The film is called Tatara Samurai. The story is set in Izumo, Japan during the 16th Century—a period of constant warfare. The main character is a young man who admires the Samurai, leaves his home village and discovers the importance of Tatara steel making. Izumo is the birthplace of many Japanese traditions, such as “Kabuki,” “Sake,” and “Sumo” wrestling. Tamahagane or Tatara steel in Japanese swords is only produced there. This is a story about the legacy of steel making.

I heard the film is based on an original story you wrote, Mr. Nishikôri. Why did you want to make a film about “Tatara”?

N: The Japanese sword is a great work of art and its material, Tatara steel, is the best steel in the world. Curiously enough, many foreign people know more about Japanese swords than we do. The sword smith who worked on our film said that Steven Spielberg came to visit him just to buy a Japanese sword. I am ashamed that I did not even know that a Japanese sword cannot be made without the traditional steel techniques that come from ancient times. Tatara steel is the purest steel even today. It cannot be produced by the latest high-tech computer-controlled furnace. Nobody knows why the ancient Japanese knew about such high technology. I would say that this should be one of seven wonders of the world, like how to build Pyramids.

When did your idea to shoot a film about Tatara first come up?

N: About five years ago. At that time, I felt there were some tendencies that “Analog is old fashioned and outdated and digital is everything.” It was around the year 2011 when we had the Great East Japan Earthquake. Analog skills and techniques, such as intuitional judgement at the site, saved many human lives. This is one of the reasons I was attracted to the concept. Also, I was born and raised in Izumo and have heard many tales of old Japan. I found out that many expensive luxury foods in Tokyo are made by traditional methods. For example, we often pay more at barbecue restaurants where we have to cook by ourselves on a small portable stove with charcoal. Hand-made organic Miso (soybean paste) is more expensive in supermarkets. We can buy cheaper ones that are mass-produced and have better preservatives, but food additives for preservation are sometimes not good for one’s health. I thought analog technologies could be better for people and “Tatara” is a good theme. Just then, I discussed with Sako-san (Cinematographer) about the advantages that film still has over digital. It’s OK if people do not notice this, but it seems that too many are saying that digital is better than film without knowing the reason. We are in an age of many uncertainties. Somebody says something in the media, rumors are easily spread and turned into common knowledge, while truth may be ignored. I wanted to tell a story about the many good “analog” things in Japan through the film.

When did you decide to film “Tatara” on film?

N: It began at a meeting with HIRO, Executive Producer of the film and former leader of the Japanese band EXILE, a popular vocal and dance group in Japan consisting of 19 members. He loves movies and had always requested 35mm film when shooting his music videos. My previous film, “Konshin,” was also shot on film. When we met, we were excited to talk about our next film and we agreed to do it on 35mm film.

But many features are shot on digital. What about Alexa?

N: I love to shoot beautiful natural scenery and I had many ideas about locations. I think this film has twice as many nature scenes as typical films. I was concerned about representing the sun, water and other natural scenes as beautifully in digital and was a bit frustrated. Sako-san agreed with me and we decided to go with film. Furthermore, many objects in the story, such as flames and swords, are analog things. Sako-san and I arrived at a conclusion: Tatara-buki is a technology of 1,000 years ago but is still state-of-the-art. Film is a technology invented 100 years ago but is also still the state-of-the-art. In addition to that, I have to thank HIRO, who led the project. Even though we know film is good, recently it is not easy to actually shoot a feature with it. However, he allowed us to go ahead and do it without hesitating. From that sense, we had an ideal environment to shoot on film.

Were all scenes shot on location? Are there any studio setups?

Were all scenes shot on location? Are there any studio setups?

N: All the scenes were shot on location. Nothing was shot in a studio.

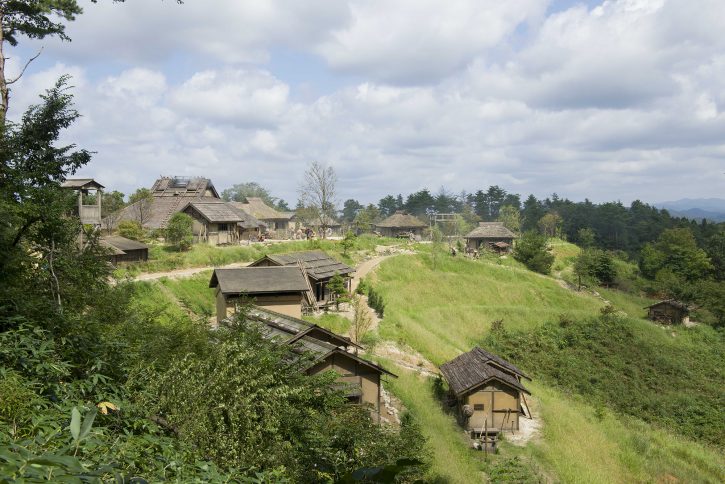

Were the village scenes an existing location in Shimane prefecture?

N: No. We built the village there as an outdoor set for the film— but it does not look like a set. There were many difficulties. We had to make everything from scratch. It took a lot of time, but we built a traditional forge in the village and really produced Tamahagane/Tatara steel. Buildings in the village were constructed by carpenters, plasterers and local crafts people in Shimane. For example, the Kagura hall (a stage for traditional performing arts) was built without using any nails. All the costumes were made from hemp fabric based on historical background research.

Recently, many features only emphasize the story line. I regret this trend and want audiences to feel the atmosphere of each image. The dynamic and vivid pictures shot by Sako-san, who has much experience and expertise, are a testimony to shooting on film.

FDTJ: What were the challenges of shooting film on location?

FDTJ: What were the challenges of shooting film on location?

Cinematographer Akira Sako, JSC (S): When I shoot on film, I do not have to think about unnecessary things and I can concentrate on my work. I do not have to play tricks and can just shoot things as straightforward as they are. I was able to reproduce and express the natural colors of flames, leaves and other elements using motion picture film. The sword smith told me that they are always checking the colors of the flames to adjust and control the temperature of the forge. In the digital world, bright areas can become overexposed at a certain level: for example, sparks of fire will be just white dots. We wanted to capture the natural color of the sparks and film’s power of maintaining their original red color was great.

N: For me, the only issue was cost. I have shot all my features on film except for “Wasao.” So I am used to it and I personally think film is more convenient than digital. I think it was the right choice to shoot on film to describe the existence of Japanese people from ancient times, who lived together with nature and with their “analog” sense that we all used to have.

What cameras and lenses did you use for the project? And how did you select them?

S: Our A and B cameras were Panavision Millennium XL. The C camera was an Arriflex 235, chosen because of its mobility. Lenses were C-series Anamorphic lenses and most scenes were shot with them. We rented a set and shared them among all three cameras. Also, we had an Angenieux 25-250 HR Anamorphic modified zoom lens. The Arriflex 235 was always ready for shooting nature scenes. The sun and clouds were always changing and never waited for us.

I think it is a worldwide trend that vintage lenses are popular and anamorphic shooting is in fashion. The same is true here. New lenses have better optical quality and provide us with sharp, crisp and nice images, but I prefer old lenses because of their unique “taste” and look, like bokeh and flare. My descriptions sound clumsy, but each lens has its own feeling. The Panavision C-series lenses were very popular. We also used one Panavision 50mm E-series prime, which we could not do without. All the indoor scenes were shot with prime lenses.

FDTJ: How did you establish the look of this movie?

S: I avoided using filters as much as possible. That is because I wanted to represent the colors and textures that the subject actually had — unaltered. Regarding the film stock, I tried to use Kodak Vision3 50D 5203 as much as I could. I wanted the least amount of grain and the most resolution. After all, there are only 4 kinds of color film negative available in the market now. I used all four. The 200T was for the beginning of the film, flashbacks and snow scenes. 500T was for night scenes and 250D was for scenes where I could not use 50D. If 250D was not enough, I shot with 500T. Then I pushed 2 stops and compensated in the laboratory. The point is that I gave priority to the sensitivity. I had an impression that 500T can be pushed but granularity was not as good as I expected when I saw the tests. So I tried not to push it except for some scenes, such as the last scene with the children. Now, ASA 400-800 is quite normal with digital cameras. I thought the low sensitivity of film was something that would help us compete against digital cameras. I tried to make good use of low sensitivity (slower, lower ISO) and finer grain. Of course, I was particular about skin tones.

What difficulties did you encounter as Cinematographer?

S: The outdoor set was made just like a real village—we could even live there. However, we could not disassemble the buildings like a studio set. Therefore, we did not always have enough space to position our lights and we had to think of clever places to put them. It was not easy and we were alternating between joy and embarrassment. Camera angles and lighting placement was a bit awkward at times, but in the end, we could capture a better sense of reality.

I was rather surprised to see how many of our crew had forgotten how to shoot on film. In the beginning, they did not work as smoothly or effectively as usual. Some had to be reminded about working in film and some were experiencing it for the first time. So I tried to have a good overview of the working crews and all the locations. Maybe this is only in Japan but filming lasts only 1 to 1.5 months, or can be just 2 weeks, for a typical project. We spent nearly 3 months on this feature. Almost all crews make a living by doing many 2 or 3-week projects one after another. Good assistants can learn a lot but so-so ones just keep doing simple routine work and let the time pass, even if something goes wrong. I could easily see whose skills and abilities were limited. We also had an aerial sequence. I thought it was common, but some assistants had never worked with a helicopter before. This was another surprise for me.

I guess they had trouble changing mags, loading and unloading different film emulsions at the beginning.

S: I think so too, as some of them were not used to it and did not know the exact procedure of changing magazines. They had to re-learn the process of loading film. I also talked to Nishikôri-san that shooting on film is similar to the tradition of sword-making. There is no manual or textbook showing how to make “Tamahagane.” Luckily we have books for filming but the most important thing is practical experience on the set. We have to hand down expertise and skills to young people. It cannot be only with words. They must begin to understand with practice. For example, our experience of aerial shooting became relevant to the younger people once we all experienced it together. I am happy that we could hand down something to them.

On the set, the leading actor, Sho Aoyagi worked hard and well. Actors and actresses and crew all worked hard…and it was like a synergy effect.

We also shot a documentary about the sword smith in film. We met his apprentices. They were in their early twenties. There is a traditional apprenticeship system and they are not paid until they become full sword smiths. Although they get free meals, they have to work at a part-time job to make a living, perhaps as a clerk in a convenience store. I would never have met them if I had not worked on this production. They participated as extras in the movie. I was pleased to know and meet these energetic young people. I do not think it is so common in other countries that young people have such hard training.

The sword fighting scenes are impressive in the movie. One was a long, single shot.

S: That was a sword fight in rain at night. A great deal of credit should go to the sword fight arranger, Yoshio Iizuka, who also works in Hollywood, and Naoki Kobayashi, who is an actor, performer, dancer, member of EXILE and also a leader of Sandaime J Soul Brothers. They acted really well in a short period of time. I think a scene with a single shot can be achieved with good performers. If they are not good, we have to split the scene into multiple shots and have more close-ups. So I was blessed with good performers. The director and the sword fight arranger also intended it to be a long, single take. I think the timing and length during the performance is more important and better than the timing made by editing. Recently, many features are edited too much. Ideally it is better to shoot the real performance with a long, single shot. I tried to do so in this feature.

Did you use a dolly on the long single shot of swordfight scene?

S: That was shot with a crane because the ground of the outdoor set was not at and was bumpy. The village was located on a hill. It was also difficult for the crew to carry all the film equipment up to the village.

Do you want to keep shooting on film?

S: I would love to, if possible. I do not know which direction digital cameras will go, such as HDR and high resolution, but I also recognize the great capabilities of film. I want to tell everybody that film is another option. I will be more than happy if film becomes more popular again. I hate that I have no choice. I do not say film is superior to digital in every aspect. Film has some advantages and digital has other advantages. Needless to say, we must digitize films, since projection is DCP now. But I think film was the right and reasonable choice for our feature, a human drama set in nature, where both natural color and skin tone are important. I do not denounce digital shooting and I also shoot in digital.

I also worry when I hear some Japanese producers tell me things like, “Film is no longer produced” or “There is no laboratory in Japan” or “It is not possible to shoot on film now”. These statements are not true. Even these producers should be able to have the choice of film or digital as recommended by their cinematographer. I hope that not only camera assistants but all crews will be able to continue to experience film shooting. I do not say it is easy but they should have the chance.

At the moment, “Tamahagane” is only produced in one place, in Izumo. Film is the same. Only Kodak manufactures film now. Once they stop, no doubt, it will be far more difficult to shoot on film, even if we wish. So we have to do our best. From that sense, I think the theme of our feature and film are quite similar. Not only in Japan but also in the world. Everybody in the industry has to work hard to hand down the culture of film to the next generation, including practical techniques and skills.

I will be glad if people who watch our movie might want to shoot on film next time, rather than telling me “Good job” or “It must be tough to shoot on film.” I hope they acknowledge the power of film with this movie.