The Pendulum of Styles

The following review was uncovered in the dusty archives at the Duchy of Grand Fenwick Cinematheque. Then, as now, style was a dialectic. Artists experimented. Tastes changed. Academies and the Establishment were challenged. In one year, 1876, we see a spate of styles. Bold artists attempted to distinguish themselves from their confrères. At the same time, the specter of still photography loomed. It was not only an artistic but also an economic challenge. How could an artist like Meissonier continue to justify fourteen years of work on one painting when a photographer like Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (Nadar) could ascend in a balloon and shoot aerial stills in one day?

The authenticity of this document cannot be validated…

Ernest Meissonier Friedland. ca. 1876. Metropolitan Museum of Art

1876. One hundred years have passed since the United States declared independence. Sixty-nine years have gone by since Napoleon defeated the Russian army at the Battle of Friedland. And on a fine day today, in 1876, American department store magnate Alexander T. Stewart has purchased Ernest Meissonier’s Friedland painting, sight unseen, for the astronomical sum of $60,000.

It is understandable. Meissonier is the highest-paid artist in France. He specializes in painting scenes of action, adventure, and romanticized battles. With an attention to detail that some call obsessive, and others will later see in Kubrick, Ernest Meissonier has been working on Friedland for fourteen years. He installed what he called a dolly in his vast garden near the Seine. Workmen pushed the dolly at breakneck speed as Meissonier perched handheld with a sketch pad to capture the precise details of horses galloping back and forth.

Friedland will surely inspire future artists with its attention to detail and 4K resolution. It’s clear that Meissonier, who goes by the nickname “Chèvre” (goat) used a wide angle, 14mm Master Prime lens. “It’s all about composition and detail,” he says.

James Tissot, A Passing Storm. 1876. Beaverbrook Art Gallery

The same year, 1876, James Tissot (the former Jacques Joseph Tissot) paints his mistress and muse Kathleen Newton in A Passing Storm. Like Meissonier, Tissot is fabulously wealthy while his Impressionist friends are struggling. Tissot also favors a 4K canvas and fine detail. His lighting is golden, backlit, contrasty, HDR. e camera notes are difficult to decipher, but we think we can make out the words “25mm Summicron-C, no filter, Mole LED 3200K Tener with Rosco 1/2 CTO coming through window.”

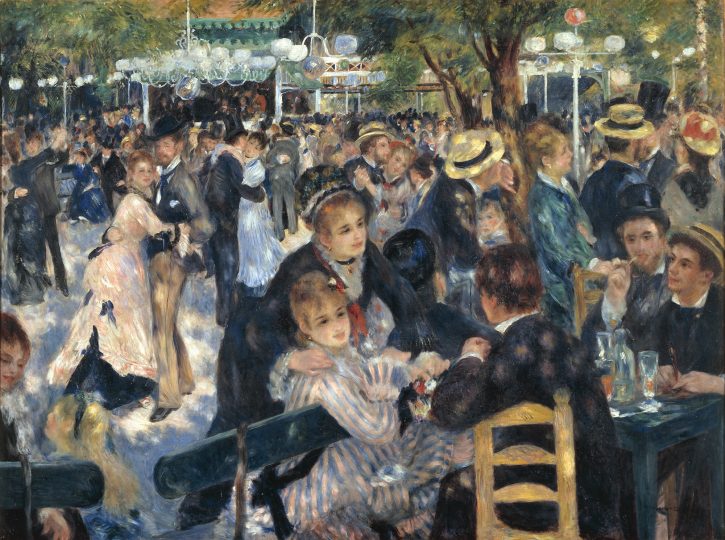

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du moulin de la Galette, 1876. Musée d’Orsay

Enter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. “All our canvases, paints and brushes come from the same suppliers,” he complains to colleagues one alcohol-drenched evening at the Café Guerbois. “Ever since that American, John Rand, invented metal paint tubes, all our images feel the same. They are too pristine, too perfect, too digital.” Renoir longs for the good old days when men were men, and painters ground their own pigments. Or, at least their assistants did.

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé. 1876. Musée d’Orsay

“Zut alors,” shouts Manet. “What we Impressionists should do is to removing the whitewashed coatings of our canvases. Make them vintage. Blunt our sharp paintbrushes so our once fine lines become blobs and blurry blotches of light. Search the flea markets for vintage palette knives. And above all, dapple the light.”

Meissonier argues, “Friedland is a period piece, but I avoid the technical path to a vintage look.” Tissot jumps in, “I prefer to avoid flares and glare to get a vintage air. I hope my lighting, com- position and art direction tell the story.”

Plus ça change…

Pingback: Lighting with Paint: Vintage 1876 | roberto cimatti