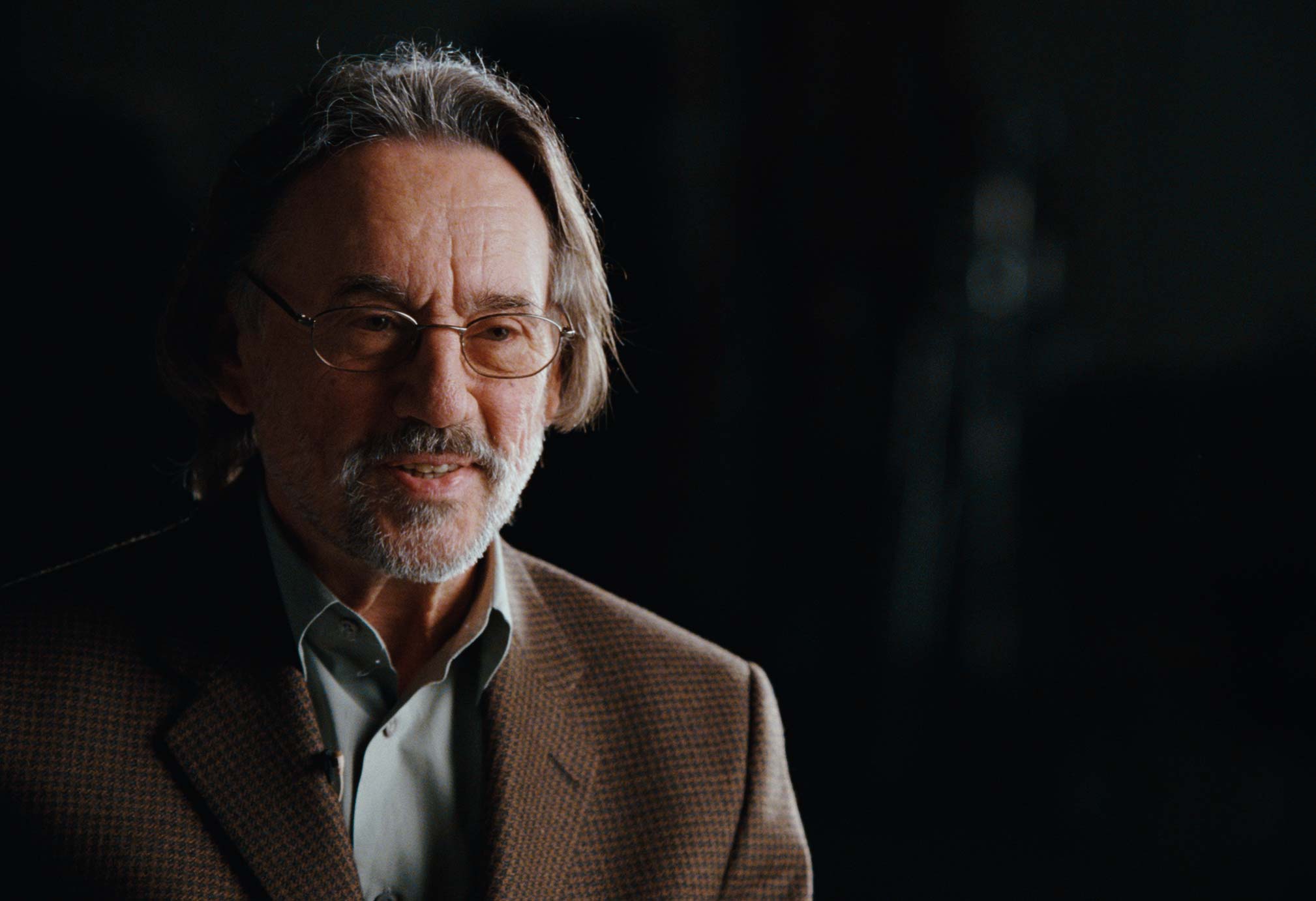

Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC passed away on January 1, 2016. He was born June 16, 1930 in Szeged, Hungary.

In 1956, he filmed the Hungarian Revolution and escaped to the West. He originally wound up in Germany. But then he said, “As long as we’re this far, might as well go to Hollywood.” His first jobs as cinematographer were low-budget films for drive- ins and television. In 1971 , Robert Altman hired Vilmos to shoot “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” which opened doors of Hollywood. He then worked with Altman on “Images ” and “The Long Goodbye.”

His next films have become classics: “Deliverance” ( John Boorman), “The Deer Hunter” and “Heaven’s Gate” (Michael Cimino), “Cinderella Liberty” (Mark Rydell), “Sugarland Express” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (Steven Spielberg), “Blow Out,” “The Black Dahlia,” and “The Bonfire of the Vanities” (Brian de Palma), “You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger,”Melinda and Melinda,” and “Cassandra’s Dream” (Woody Allen).”

In 1977, Vilmos Zsigmond received an Oscar for best cinematography on “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” In 1997, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award at Camerimage, and in 1999 from the American Society of Cinematographers. His credits are long.

In 2014, Vilmos was honored with the Pierre Angenieux EXCELLENS Award at the Cannes Film Festival. Read his interview here.

And here’s Vilmos’ interview from “Cinematographer Style.”

Who are you and what do you do?

I am Vilmos Zsigmond. I was born in Hungary, and I am a cinematographer. When I was 26-years-old, I finished film school in Hungary. When the revolution came in 1956, I left the country, came to the United States and started everything from scratch. Ten years later, I started to make big movies.

How did you become a cinematographer?

I went to film school in Hungary for four years, and they put me into a studio that would have helped me become a feature cinematographer, but, as I mentioned, there was a political revolution happening and I had to leave the country.

What happened during the revolution?

During the revolution, many cinematographers were shooting documentary footage. The Russians came and we didn’t know what to do with the footage, so we had a secret meeting and decided some people would have to go to the West and take the footage with them. I volunteered, because I had reason to go because, at that time, my father was working in Morocco. So I found my friend László Kovács, ASC, and one other person, and the three of us escaped with the film to Austria.

How did you become a cinematographer in the United States?

First of all, I had to learn English because I didn’t speak a single word of it and, though my French was better at that point, I decided I wanted to be as far away from Hungary as possible, so I came to Hollywood and became a cameraman. Of course, that is easy to say today, but in reality, I didn’t know the language and I didn’t know anybody. I went to meet with Hungarians who were in the business then, like Zsa Zsa Gabor, thinking they could help me get into the film business, but it didn’t work that way — they said they would help if I could show them what I could do, but if I could show them what I could do then I wouldn’t need their help anymore.

What was your first break?

I had several breaks actually, but my biggest break was doing a movie with John Astin called Prelude. It was nominated for an Academy Award. It was a wonderful little movie about the supermarket, and John directed it, wrote it and played the leading role. The film was very successful and a lot of people in studios remembered it, so when Peter Fonda decided to make his first feature film, The Hired Hand, he hired me to shoot.

How do you determine the style of a movie?

That is a tough question. First, I read the script and I might have some ideas about the look. Then, I sit down with the director who often has certain ideas about it as well, in terms of how he is going to direct it and his style of directing the actors. But even after those conversations, I don’t think we know what the style is going to be. I, personally, have to see the locations first; location is very important to me.

Say you get to a location early in the morning and have your coffee — what happens next?

By the time we are in production, we have seen the locations and have an idea of what we want to do. One important thing is determining what time to shoot at the various locations to get the best light. Morning light and afternoon light are different. For example, the midday light in Los Angeles, where the sun is right above you and it is 90 degrees, is not very good for cinematographers. I don’t like that light, unless it is a movie like High Noon, but very seldom would you want to shoot in those conditions. I like shooting in the morning and afternoon, with maybe taking off in the middle of the day if we can afford it — which never happens. So we have to manipulate lighting in whatever way we can to create a look that matches from morning to evening.

What is the difference between morning and afternoon light?

They are similar, but both are very different from the midday light. The main difference is the angle. For example, in Sweden, there is always beautiful light, even in the summertime when the light is coming from a lower angle, which still gives off a nice key light, a very moody light actually. Unfortunately, in California we don’t have that, so that is why I have to determine which scenes have to be shot in certain light conditions. The light is magical at dusk, for instance. We call it the magic time: the last few minutes before the sun sets. That magic goes on for only a short time and cinematographers love to work in those conditions.

What are some examples of features where your style has changed?

I was very lucky to work with Robert Altman on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Robert was really someone who searched for different styles on each one of his pictures. Before working with him, I was not too keen on using zoom lenses, but he taught me how to use them during that movie — not necessarily to use the zoom as a zoom, but to be practical about setups. He was a master at that.

We also wanted to have an old, antique look for the movie and, in those days, we didn’t have much of an example of this style, so my idea was to ‘flash’ the film. It was not my invention, as I think Freddie Young, BSC was the first to do it, but it worked perfectly for what we were trying to do. We desaturated the colors, because in those days everything had the Technicolor look in Hollywood, which meant very bright, very saturated colors, and we wanted this movie to look very old, like a faded color photograph. So we decided to shoot all the exteriors with a bluish look and the interiors with a warm look. It was natural to do that, because when the film went from outdoor to indoor, the lights — which were mostly candles and lanterns — looked much warmer. And the overcast skies and rain in Vancouver, which was where we shot, really helped us create a special look for that movie.

How does that experience compare with other films you’ve worked on?

With Robert Altman again, I did The Long Goodbye, which had a completely different look. We still flashed the film to desaturate the colors for a more natural look, but we also added a lot of camera movement; the camera was always moving, whether it was on a dolly, moving left or right, up or down, and zooming in or out. We used, virtually, all the possible moves one can use with a camera.

The interesting thing was that we moved the camera whether or not the story called for it. I felt ridiculous, always moving the camera for no reason, but Robert said not to worry and that people will like it — and they did, even the critics. We got the cinematography award from the National Society of Film Critics that year. Looking back, it felt strange to me, because that movement was new. But it created the missing third dimension in this art form, as it suddenly gave a certain depth to see objects in that dimension, because whatever was closer in the foreground moved faster than the objects behind it. That was an interesting way to think about it. It is better to move the camera only when you need to, as opposed to always, but we definitely established something.

What is the relationship between technique and technology?

When I look at today’s movies, I see a lot of handheld camera movement creating an immediacy of the shots that makes it look more real, which is not something I believe in 100%, but it works marvelously in certain movies. This style requires lightweight equipment, and today we have cameras that are very lightweight, like the Aaton, which is like shooting with a video camera. Things like this help us to create different styles for different movies.

How did style evolve on some of your other movies?

On McCabe & Mrs. Miller, we changed the style within the style. In the beginning, we were flashing heavily to create the antique mood of the film, but in the end, we pulled back the flashing and diffusion to make it look more real and dramatic as McCabe dies. Later on, I used flashing in several more films like Images, and in The Long Goodbye, I used even heavier flashing.

Next came Deliverance, which I did with John Boorman. We created a whole different style for that movie. John loved what I did in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, and that is why he hired me for Deliverance. He was watching dailies at Warner Bros. and knew that if someone could do what I did for McCabe & Mrs. Miller, then that person could do something else as well. It is interesting how many times people try to put cinematographers into a box. Irwin Winkler once said that he actually selected cinematographers for their style. I really hate the idea that I could only have one style and that people would box me in, thinking the diffused look of McCabe & Mrs. Miller was my one style instead of a style created for that one movie.

On Deliverance, we were in Georgia in the springtime and everything was so bright, colorful and beautiful, but it didn’t really fit the story. We wanted a look that was realer than real life, so we shot it very sharp and then desaturated. To keep the images sharp, I used the three-color Technicolor dye-transfer process and added a fourth layer in black-and-white. For the dramatic river scenes with the rapids with canoes breaking apart, we were lucky to shoot those in overcast conditions. We actually had weeks and weeks of overcast days, and John Boorman, being from England, loved it. When the sun came out, we would stop shooting. Sometimes, we waited hours for clouds to cover the sun. The mood and style of that film was important to get right.

Does style come from within?

I don’t really believe that we have a style ourselves. I think it is wrong for a cinematographer to have a style, because you can’t shoot every movie with the same style. I’ve noticed that many contemporary cinematographers only use soft lighting but, to me, soft lighting is very boring unless it fits the subject. I prefer to use directional light. I’m old-fashioned enough to like Fresnel lights, and if I want them softer, I can soften them using a material in front of the light; and if I want harsh light, I can just pull the diffusion away. I also love to work with natural sunshine. In the past, I’ve had problems learning to light daytime interiors and the secret, I’ve found, is to use the harsh light coming in from the windows.

How do you light the actors?

I prefer to use soft light for actors and actresses, who often want to look better than they actually do, especially women stars who have a tendency to age like everybody else but who still want to look like they are in their twenties. The soft light is beautiful for people’s faces.

Lighting is very important for cinematographers, because the type of lighting we use actually creates the mood for the scene. Many of my contemporaries use soft lighting for everything, be it drama or comedy. I hate that kind of approach because I think each film should have a different look. Personally, I think soft lighting can get boring. I’ve studied a lot of Dutch painters who hardly ever used soft light. They actually used a lot of directional light, which is what I also like to use.

For example, for The Deer Hunter and Deliverance, soft lighting would not have been appropriate. If sunlight is coming into a room, I would use a hard light because the sunlight should be very bright and contrasty. The lighting ratio of sunshine is about 16:1, as opposed to a soft light situation, which is about 2:1. Hard light is more difficult to use, but when used properly it is more effective at creating a drama look. Good cinematographers don’t only use light, they also use shadows, and because lights create shadows, the shadows are more important.

5218 is my favorite film stock. I wish I had this film stock a long time ago because I used to have real struggles. When I was using 5279, for example, I found it too contrasty. I love contrast, but the film cannot be contrasty and, many times, I will use a film stock on the softer side because when I use hard light, I like to soften it up a bit. Hard light and soft negatives are what usually satisfy my tastes.

Let’s talk about in-camera effects versus postproduction effects.

On location, I like to do everything I can to create the mood and effect in the scene. For example, I might use graduated and polarizing filters to darken the sky, and I can do that better on location than I can in postproduction. Many people say you can do anything you want in postproduction, and that may be true, but just think of the time spent. Also, I don’t think it would look as real as it does when you do it on location.

Will film be around forever?

With digital photography, I would love to see it become as good as film. I don’t know how long that will take, but at the present time I love film so much that I don’t want to switch over, as far shooting is concerned. As far as postproduction goes, that is a whole other story.

I love the idea of the digital intermediate, which lets us change things that we could not change when we were shooting. It is a great tool. However, I do not want to shoot digitally, but maybe I might change my opinion in ten years. For now, a gorgeous stock like 5218 is so unbelievably beautiful, why change it? I don’t think the cost is really that much more to shoot on film either. Then again, digital photography allows us to do so many things, like in The Lord of the Rings or Peter Pan.

Let’s talk more about digital postproduction.

With digital intermediate, cinematographers can really improve the look of our movies, but we have to be involved with the picture from beginning to end — from the first day we scout locations to working with the production designer, actually shooting the movie and into postproduction. This is because we have to maintain the mood of the film we created on set, so we have to make sure nobody takes us out of that process. As cinematographers, we are creating the images so we should follow them until they get to the screen.

Further recommended viewing: “No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo & Vilmos” by James Chressanthis, ASC.

Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC signing autographs at Band Pro Booth at Cinec in Munich. Photo by Curt Schaller, BVK.

Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC received the Pierre Angénieux EXCELLENS in cinematography award at the 67th Cannes Film Festival on May 23, 2014. Photo: Pauline Maillet.