Jon Fauer: The last time we spoke, you were prepping Top Gun: Maverick. You were asking Mr. Yamaki, CEO of SIGMA, to add /i lens data into SIGMA High Speed Full Frame Cine lenses.

Claudio Miranda, ASC: I remember becoming frustrated because I was using SIGMA E-mount lenses that included Sony lens metadata. But when SIGMA Full Frame Cine primes came out, they didn’t have lens data. And so, they were kind enough to add it back in for me because I like to see focus distance and T-stop in the eyepiece or on the monitor.

Because of you, SIGMA added /i lens data to all subsequent models of T1.5 High-Speed Full Frame PL mount primes.

We were looking at a bunch of lenses during tests for Top Gun: Maverick and we gravitated toward these SIGMA lenses based on some stills that we saw earlier on. But in truth, Top Gun: Maverick used a bunch of lenses. The list is kind of crazy.

Danny Ming, Top Focus puller, sent the list: “SIGMA FF High Speed PL mount primes, Master Primes from 65mm and longer to cover Full Frame, Voigtlander and ZEISS Loxia E-mount primes in the cockpit; 28-100 FUJINON Premista FF zooms; FUJINON Premier 18-85, 24-180, and 75-400 zooms with IB/E Optics Extenders; Canon 150-600 (FF modified still lens). The aerial and Shotover unit used 20-120, 85-300, and 25-300 FUJINON Cabrios.”

The camera and lens list is long. We mixed it up a little bit.

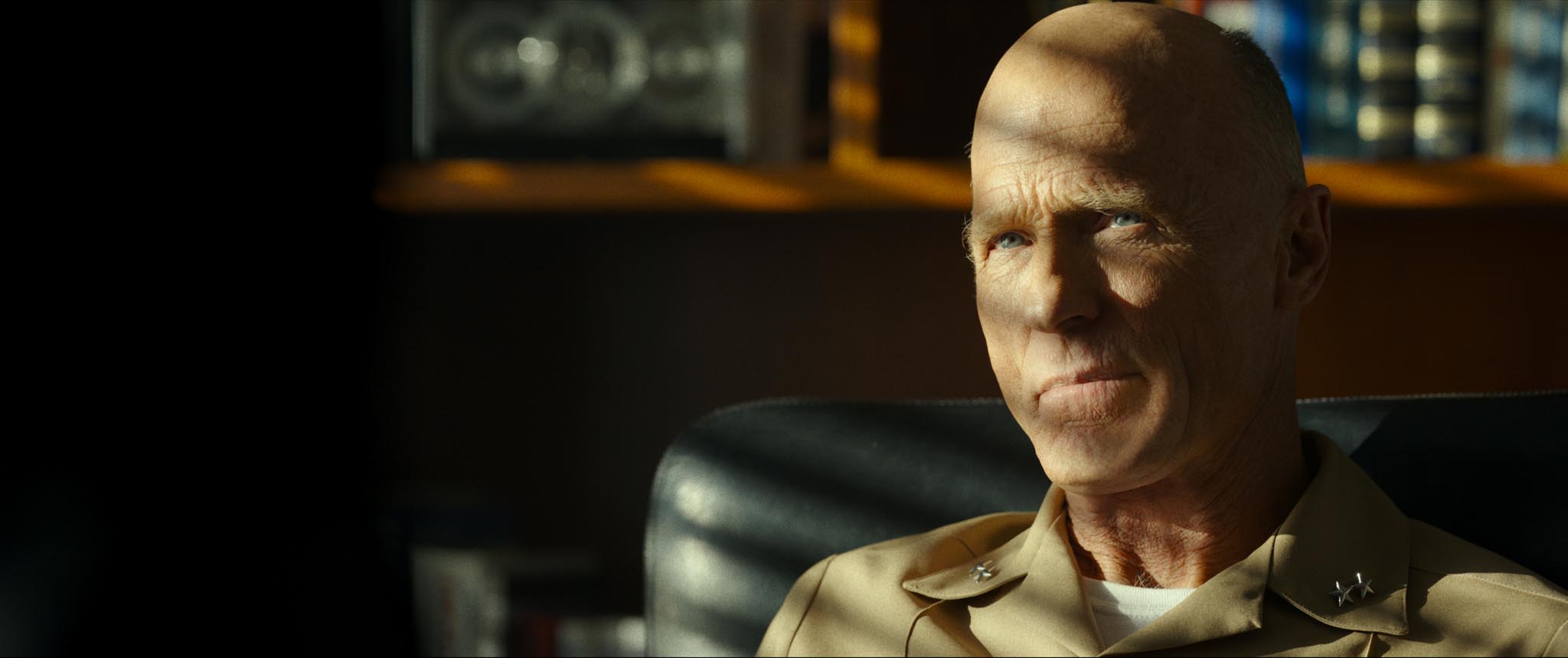

As Admiral Cain, played by Ed Harris, asked, “Why is that?”

“It’s one of life’s mysteries.” Seriously, Joe Kosinski, our Director, wanted to shoot Full Frame. SIGMA covered the wide end, and the Master Primes covered the long end. We were using the SIGMAs from 14mm to 50mm. The Master Primes in those focal lengths don’t cover Full Frame. But the 50, 75, 100 and 150mm Master Primes do cover Full Frame. In terms of sharpness and resolution, they’re pretty close. In grading, even if things are just a little bit off, you can kind of blend them all in.

Life’s other mystery, then: why did you have Super35 zooms?

We were shooting in Full Frame sometimes. But our zooms, with the exception of the FUJINON Premistas, were mostly the FUJINON Premier series, which are Super35. A lot of that was for ground-to-air on really fast moving planes going through the mountains, or just when we needed to carry a small lens package that had a greater range. For example, if you go in a helicopter, you want to carry one lens. Full Frame zooms are great, but they generally don’t have the long range of the Super35 models.

Claudio Miranda, ASC, with Fujinon Premier zoom, ground to air. Photo: Scott Garfield. © 2022 Paramount Pictures.

The FUJINON Premier zooms cover Super35, not Full Frame. But they are incredibly sharp and Super35 format on the VENICE cameras is still 4K. We were in 6K for all the Full Frame scenes. Of course, the film was released in 4K.

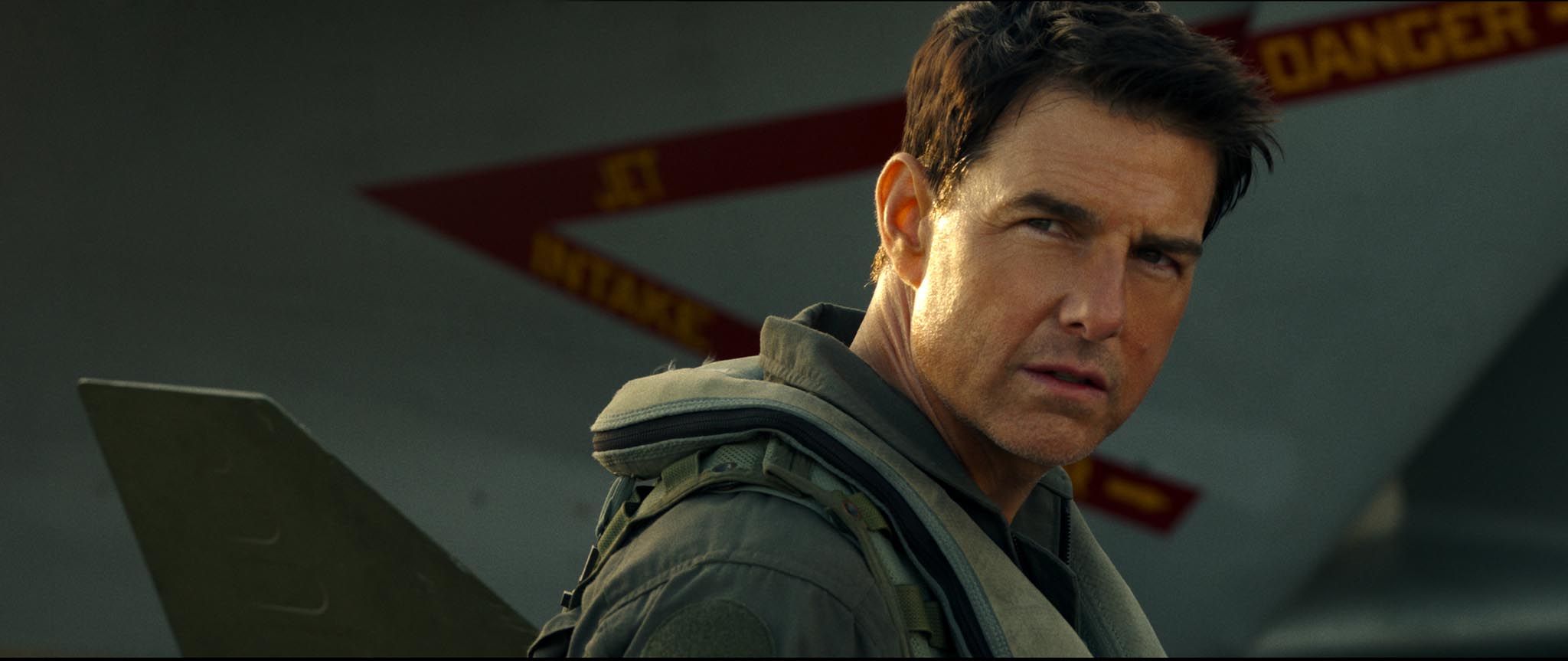

Monica Barbaro and Tom Cruise in cockpit with Sony VENICE cameras. Photo: Scott Garfield. © 2022 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

The interior of the jets were covered with Voigtlander and ZEISS Loxia E-mount, manual focus and manual iris still photography lenses. We used them because their small size allowed us to get them inside the jets. We had the VENICE cameras in Rialto mode: camera head tethered to the camera body. But we couldn’t fit the RAW recorders in the jet cockpits so we recorded everything in XAVC 4K Full Frame onto SxS cards.

So, you removed the PL Mount from the VENICE cameras?

To be as compact as we could, even SIGMA E-mount photo lenses would’ve been too big, believe it or not. We really had inches to work with, in very little space. The cameras had to allow clear ejection points for the pilot, and nothing could protrude in front of the control panel of the dash or beyond the glare shield. Not even by a quarter inch. We even had to shave off parts of the lenses just to make room.

We couldn’t add ND filters in front of the lenses. That was another advantage of VENICE: they have internal ND filters. For example, if it got cloudy, I would set the exposure based on where the aircraft were flying. I imagined their flight paths using Google Earth, and figured they’re going to go around this terrain, the mountains look pretty high here, they’re probably going to go down low over there. And then we would just kind of guess exposure and lock it in and hope for the best. I think 99% of the time I got the exposure right.

How did you start and stop the cameras?

Keslow Camera built us a little button that the actors would hit to trigger all the cameras to run. They also got feedback on a little readout to indicate what cameras were running, or not. There were six VENICE cameras in the cockpit, including the over-shoulder angles. So four are focused on the actor and two are looking forward. We had very early versions of the VENICE Rialto. As you may remember, we went to Japan and gave them a lot of advice on the design and engineering of these cameras.

Tom Cruise in narrow hallway. Sony VENICE camera up against the wall in Rialto mode, with Preston Light Ranger, SmallHD monitor, OConnor 2575 head on Fisher dolly. Photo: Scott Garfield. © 2022 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

I remember your major contributions to the development of the VENICE, internal NDs, and menus. A product manager said, “Claudio had a significant influence. By far his major contribution was the suggestion of 8-stops of internal ND, the only camera to have it. He also pushed the engineers for internal RAW recording which was implemented in VENICE 2.” That was not in time for Top Gun, but you just used it on Nyad, the feature about marathon swimmer Diana Nyad.

Initially, the Rialto was not about getting it into the jet. It was about getting it into the smaller F1 Shotover that goes on the front of the jet. It was devised so you could put the sensor block and lens in the Shotover, and then run the cable to the camera body and recorder inside the jet. Then I could attach any lens I wanted, like the the FUJINON 25-300 inside the small Shotover. And then we found it really handy to be able to use inside the jet.

Director Joseph Kosinski on TOP GUN: MAVERICK with Preston Light Ranger II above lens. Photo: Scott Garfield. © 2022 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

In what aspect ratio did you compose Top Gun: Maverick?

Top Gun: Maverick was released in 2.39:1 and 1.90:1 for IMAX. Because of framing in the jets, where pilots are sometimes inverted and we couldn’t move the camera, we framed in 16:9 and cropped in post. We couldn’t move the cameras, but we could move the pilot’s seat to accommodate the actors’ different heights to give us proper headroom.

Did you lock the cockpit lenses off with tape?

Yes, the focus and iris barrels were all locked off. Also, if you remove its PL mount, VENICE has a native E-mount underneath with a very secure lever locking mechanism that holds the lens in very tight. In fact, it has a safety locking detent, so E-mount may be even more secure than PL.

Who approved the safety of the cameras in the cockpits?

The Navy engineers determined whether it was flight worthy or not. Initially, they told me that I’d never get six cameras in there. “You’ll barely get three inside,” they said. I just said OK and started looking inside the jets every day. I noticed some video cameras and asked what they were for. And they said, “Those video cameras record internal stuff.” I asked, “Can’t we just strip out the equipment you don’t need in here? And then see how much room we have left? You don’t need to record any video, because we’re recording all the video as well.” And so they allowed me to remove things that weren’t essential and utilize that space.

In the end, we did get six cameras inside. It had a lot to do with just being there every day and politely asking questions.

There was another time when I was on the aircraft carrier with a small crew and two cameras. I was struggling a bit, trying to get the light in the right place. Someone asked me how it was going. And I said, “It’s going okay but I really wish that I could ask the captain to head in a certain direction for better light. And they said, “No, you can’t ask the captain to turn the boat. Are you crazy?” And I kind of thought, well, that does sound pretty crazy to alter the heading of an aircraft carrier just for the film.

A little later, someone else came up to me and asked the same question—how I was doing. I didn’t know who he was. I said the same thing as before, that I was bummed out that I could not turn the ship to favor the light. He said, “Sure, that’s not a problem. We can do anything you want.” And he indicated they had something like 23 years of fuel on board.

He asked, “When do you want it? I said, “At four o’clock, it’d be great if the ship was heading 90 degrees. That would put the sun in a perfect place for us.” I didn’t think it would truly happen. But at four o’clock, the whole aircraft carrier turned and headed in the right direction, due east.

It’s like many things in life and business: people can be afraid to talk to the person above them. But just by chance, I happened to pass the right person in the hallway. I called our liaison officer the best gaffer we ever had. And then it got even more incredible. We were turning the ship all the time. They would ask where we wanted it now and then change course accordingly.

Later in the schedule when we had to do the full-on shooting with Tom Cruise and everyone, I said “When we were on the Lincoln a few months ago, they let us change course according to the best sunlight.” Of course they couldn’t be upstaged. So they left an officer with me who was in charge of wherever we wanted the ship to turn and he was always really helpful.

They could even control the headwinds by turning the ship. The only difficult thing was if the ship was going right toward the sun and the pilots had to land on the deck—they were a little hesitant about that one, which I understand. They would just veer off a little bit so the pilots weren’t getting totally blasted by the sun on take-off and landing. There were some limitations.

Did they turn 180 degrees so you could get reverse angles?

Oh yes. Whenever we were doing a reverse, I just always kept them backlit, or three-quarter backlit, with the sun behind the actors. They just turned the whole aircraft carrier around.

Was it similar with the aerials, finding the light?

Yes. We talked to the actors, we talked to the pilots, we had ground briefings all the time. For continuity and to have good backlight, I always wanted the actors to have the sun behind them, from 4 to 8 o’clock. As long as the sun was behind, that was our direction. This was great for the four cameras facing aft, facing the actors. But it wasn’t as good for the two cameras facing forward, which was front-lit. With multiple cameras, one angle is going to suffer. But I figured this was about getting the beats and maybe there’d be some shots where the jet was turning. So, we had two jets flying at the same time, with six cameras in each. We had another four cameras in pylon positions on the wings and additional cameras underneath looking forward or backward. There were a lot of cameras and lenses working on Top Gun: Maverick.

Framegrabs