Canon Sumire Primes — Episode 2

This the one and a half year anniversary of our first discussion about Canon Sumire Prime lenses. The adventure continues.

Since their introduction in April 2019, Sumire Primes have distinguished themselves on features, TV, series, spots, docs, reality and many productions. They are unique at Canon in that products are usually not given names, like Sumire, but rather letters and numbers, like C70, R5, CN-E and K-35.

Consider this as the second episode of our Sumire Saga. It’s about Sumire look, design, science and art. Spoiler alert: it’s not about vintage lenses, as we find out from Canon Senior Fellow Larry Thorpe.

Background

Larry Thorpe is a distinguished Senior Fellow at Canon. He and I had the good fortune of traveling together in February 2019 for a firsthand look at Sumire Prime design and manufacturing in the Canon Utsunomiya Lens Factory (photo above).

During our February 2019 discussions in Japan, Larry said, “The recent move to Full Frame sensors has changed the cine camera and lens landscape. And so, we figured it was time to think about what Canon might offer with a new look in a set of prime lenses. Our new Sumire Primes are the results of those efforts.

In a meeting at the Utsunomiya Lens Plant, Ryuji Nurishi, Senior Optical Designer, said, “Both art and science are essential in lens design. It’s really about pursuing a level in the design and also the ‘Monodzukuri’ (the way of making things) that can take it to a higher level. That involves aspects of science. High technology is required. But there’s also a great degree of craft, art and artisanship. It’s about the nuances, the instincts that people have, and combining all those things together. You have the latest technology but are always pursuing an ideal level, if you will.”

Yasuyuki Tomita, Senior General Manager, added, “For me, optical design is almost like painting a picture. Different people take different approaches as to how they might interpret a subject and how they would express themselves in creating a painting. Certainly, if you translate this concept to the cine lens industry, it’s about the different philosophies of the various companies.

“Different people have different ways of designing and creating. Even if we pursue the best technology in a lens, if the person who uses it, the DP for example, does not appreciate it and cannot bring out the best in it, that’s why you have to have a good balance of both science and art.”

Recently, Mr. Nurishi added another word to my lens and philosophy vocabulary: “San-ji.” It is one of the guiding principles of Canon and refers to self-motivation, self-management and self-awareness. He said, “The essential process in the design of Sumire Prime was to translate the “look” which was requested in terms of artistic expressions by the DPs and rental houses, and to define the target optical characteristics to achieve it (Seidel’s five aberrations, two chromatic aberrations, color balance, ghost, flare, etc).

“Our design approach included multifaceted simulations with super computers. These were just tools. The major work of translating artistic expressions to optical characteristics can best be explained as extremely independent and proactive designs that were achieved primarily by each optical designer’s own sharpened senses, Canon’s optical design technology cultivated by our long history, and the uniqueness of Canon’s optical designers who have been trained in the San-ji spirit.”

At our 2019 meeting, I asked Mr. Nurishi what Cinematographers’ requests resulted in these latest Sumire lenses? He replied, “Creamy. Organic. Pleasing skin tones. But sharp for the eyelashes and hair. Gentle focus fall-off. Beautiful bokeh.”

To my question about what it means to a lens designer when DPs say they would like a vintage, old-fashioned look, he did not look heavenward. Instead, he patiently replied, “20 DPs will have 20 different definitions of ‘vintage.’ In the days when we used film, as a lens maker, we were always providing lenses that possessed the finest line pair resolution—the finite, if you will. But depending on what brush you use, and I’m talking about the finite, how thick is it, how big? The brush, the lens, actually changes the expression of the art and that’s what DPs are looking for: different types of expression depending on the paintbrush that they would use.

The Sumire Prime was designed for the purpose of creating the best way to represent, to film, a human being. That’s the paint brush. The Sumire is for the human face.

Larry Thorpe smoothing a lens at Canon’s Utsunomiya Lens Factory, under the close watch of Lens Meisho (Master Craftsman) Toshio Saito.

A Lens for Formats S16 to S35 to Full Frame and Resolutions 2K to 12K

Larry Thorpe added, “A central design priority of the Sumire Primes has been to do justice to the remarkably high-resolution capabilities of Full Frame digital cine cameras. The new Sumire Primes achieve the requisite sharpness in the central range of lens aperture settings. Lens resolution is bounded by diffraction as the lens aperture is stopped down and by the collective of the multiple optical aberrations as the aperture setting approaches wide open. The optical designers worked on fine adjustments to the aberrations that created a gentle modulation of the lens sharpness that imparted a subtle and aesthetic nuance to a broad range of facial skin tones. It further imparted a smoothness to the transition between in focus and out of focus regions of a scene. We learned a great deal from cinematographers as to what they wanted. We listened closely to camera crews and rental houses. We heard them talk about character, special personalities and unique characteristics, and of course, the vintage look.”

And so we get to the word “vintage.” Despite an optical design to the contrary, by November 2020, quite a few Cinematographers were referring to Sumires as “vintage.” It was time for a Zoom meeting with Larry to clear things up. Or should we say, “To scotch the rumors.”

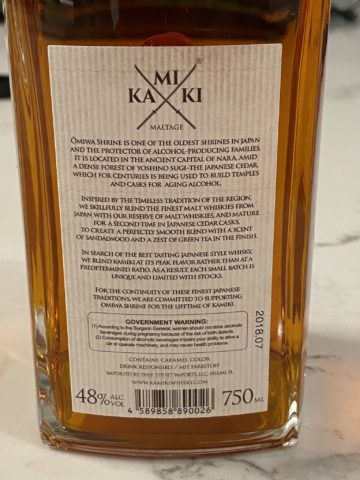

This we took quite literally. It was after hours, after magic hour, as I poured a glass of Kamiki and Larry a loyal Jameson. This was not out of line, as descriptions of lenses often follow cues from the worlds of art, wine and whisky tasting.

Larry and I had visited Japan a number of times. In fact, it was in Kyoto where he introduced me to the almost optically clear and perfectly spherical ice cube. The concept is surface area reduction and therefore less dilution of the drink. The look of a glistening orb in the golden glow of a Yamazaki 18 quickly encouraged lens analogies.

Meanwhile, back at our recent Zoom meeting, the Kamiki Whisky label reads, “Omiwa Shrine is one of the oldest in Japan. It is a tutelary shrine of the Japanese alcohol producers. It is located in the ancient capital of Nara, amid a dense forest of Yoshino Sugi, Japanese Cedar, which for centuries has been used to build temples as well as casks for aging whisky. Kamiki is balanced with heather honey, sweet caramel, Japanese plum, balanced oak, peat and toffee with hints of sandalwood and green tea.”

That almost sounds like a DP poetically extolling the virtues of a Sumire lens. But are they vintage? I asked.

Jon Fauer: So, Larry, do Sumire Primes indeed carry on the Canon legacy of vintage K-35 lenses?

Larry Thorpe: Let me start by saying no to “vintage.” In all of our discussions over the years since we entered the cinema market, Directors and DPs all over the world gave us three types of input. There were certainly constituents who said, “We love vintage lenses. Canon, could you develop vintage lenses?” There was a second constituent who said, “We don’t believe in vintage lenses. We want a contemporary lens that is sharp over most of the aperture range. But on facial closeups, when we typically open the aperture wide or wide, we would like to see some modulation, if you will, of the sharpness, but only as we approach the wide open.” Then there was a third constituency who were saying, “We’re stuck with digital. Digital is getting higher and higher in resolution; we think it’s too sharp. We want lenses to soften that a little bit.”

We had to wrestle with these three slightly different messages. I should add to that, on the vintage discussion, many people have said to us, “Canon, you mastered the beloved K-35 primes. They were manufactured in the 1970s and 1980s. They won a Sci-Tech award in 1976. Can you recreate these vintage lenses?”

We responded, “Sorry, the vintage look of the K-35 series is a result of many factors. The first is the fact that optical design and manufacturing capabilities of four decades ago don’t compare with those of today. Then there is the deterioration of the lenses over the past 40 or 50 years. This includes the inevitable creeping physical ageing of the individual glass elements themselves (that affect optical performance), changes due to accumulated physical perturbations to the lenses over those years, further changes due to element wiping, scratches, fogging and dirt. And finally, there is the progressive deterioration of the optical coatings on the lens elements. And all of that has been different from lens to lens.” Very few K-35s today look the same. They all have a vintage look, but they’re different. So, we said no to that.

Instead, we decided to coordinate the comments we received from those DPs and rental houses worldwide, seeking an appealing look with the long experience of our optical designers and ally that with the use modern, high-powered computer simulations in a quest for that look.

We sifted through the many descriptors we got from different DPs of what they want in a contemporary look. And they used descriptors, they used adjectives, rather than technical. They’d say, “We want a creamy look. We want the nose to ear to have a slow focus fall-off.” Some DPs were able to be a little more descriptive – and this was particularly important for our optical designers. The computer simulations showed that we could design a modern lens that had the desired look as you approach wide open. And that is what we did in Sumire. It’s very important to understand that we distinguish it from vintage. We’d never, ever say that Sumire is vintage. Some people may say, “Oh, the look is vintage.” And that’s all right, if that look meets their own individual definition of the unique look they seek.

That’s a good description. They are smooth and gentle on skin tones. The look is consistent and the mechanics are excellent.

There was an overarching teamwork underlying the design of Sumire. This included the regional sales organizations around the world who reported on the desires of DPs and rental houses, the regional marketing and product teams who very effectively transmitted those desires to the design team in Japan, and, of course, the positive responsiveness of those experienced designers to these multiple inputs.

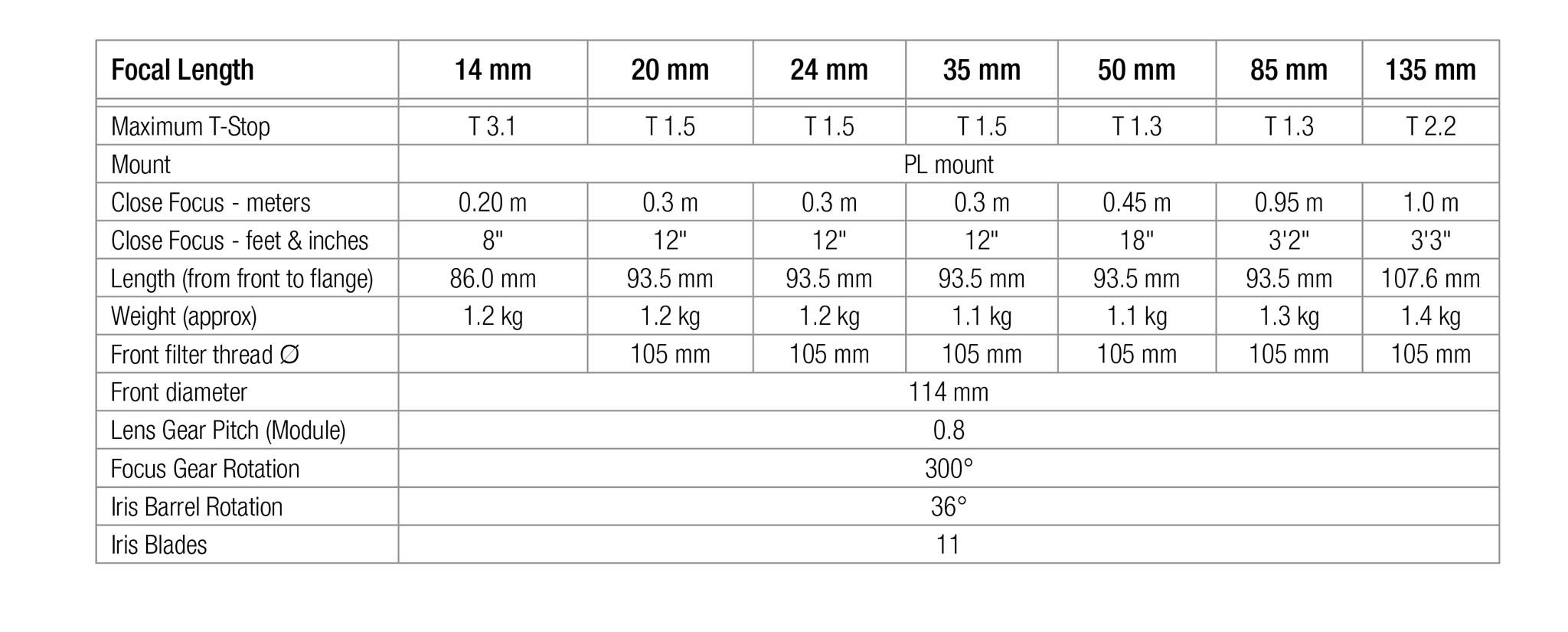

These are lenses that embody the very best of modern development techniques. The optical characteristics being sought had to consider F number, depth of field, color balance, ghost, flare, etc.—and of course, optical aberrations. You have high resolution over most of the aperture range – but, as you get to F4, it slowly starts to migrate into this look that increases as you go all the way to wide open of T1.3 and T1.5.

Practically or hypothetically, we have started seeing 8K and 12K cameras. What happens if you put a Sumire lens on those cameras?

You will get the same effect. Sumire and all of our lenses are Cinema EOS lenses. They can resolve at least 8K. Not with the same depth of modulation as 4K, but they are certainly reproducing 8K detail. So you can put this lens on an 8K camera. On a 12K, honestly I don’t know yet. I think it will resolve.

What do you think would happen? Color fringing or chromatic aberration?

No, you just get a slight softening. The lens is behaving like an optical low pass filter. It’s not killing the detail, it’s just lowering it gently.

This might be what many people want.

Yes, it absolutely could be. My count is there are seven Super35 8K cameras at various stages from prototype to completed products by different manufacturers. I noticed myself at last NAB and IBC that many of those were using Canon lenses. When asked why, they said, “We tested a few lenses and we liked Canon’s look on 8K.

What happens when you put a Full Frame Sumire on the new Super35 Canon C70 camera using a PL to EF to RF mount adapter? What’s the look effectively going to be?

It’s going to be very much a 4K look because the C70 has a 4K Super35 image sensor. There would probably be a slight softening of the MTF. It wouldn’t be as sharp as if you had a full-frame image sensor at 6K or 8K, but it is still going to be very respectable 4K.

And now for some math gymnastics, what happens when you use a Full Frame EF lens like the Canon EF 85mm f/1.2L II USM at f/1.2 with the new Canon EF to RF adapter (EF EOS-R 0.71x)”on the EOS C70 camera?

The adapter has a fortuitous combination that preserves of angle of view and elevates the speed. You gain about a stop. And it carries all of the electronic communication between an EF lens and the camera’s RF mount.

Your example of the Full Frame 85mm lens at f/1.2 with this adapter on the Super35 C70 camera retains the same angle of view. So, the angle of view is comparable to having a 60mm lens designed for Super35 / APS-C . And you gain a stop, so your f/1.2 effectively becomes an f/0.9. Most EF lenses are optically compatible with the EF-EOS R 0.71x adapter and contribute to the effective transfer of full frame imagery to a S35mm image sensor with the benefit of a one-stop gain in optical speed.

In terms of full electronic communication – associated with the lens-camera communication through that adapter – three specific EF lenses at this juncture are fully compatible in terms of implementation of all electronic corrections for optical aberrations and high accuracy auto focus. These lenses are: EF16-35 F2.8, EF24-70 F2.8 and EF24-105 F4.0. Moving into 2021 Canon will progressively update the stored files within the remaining family of EF lenses to achieve full electronic compatibility with the EOS C70.

I like the RF mount and hope there will be more RF mount Canon Cinema EOS cameras and lenses. The RF mount opens up a universe of possibilities with its short 20mm flange depth.

It does, and in the long term, we are going to be able to make higher optical performance lenses because of that short flange back.

For example, the new Canon RF 85mm F1.2 L USM DS is an amazing lens.

Oh, that’s a beauty, a real corker of a lens. I’ve been reading reports on that lens from around the world. Everybody loves it. We did something awfully good there.

Why do so many Cinematographers obsess about vintage looks? I’ve rarely heard any still photographer asking for a similar thing?

That question requires a delicate answer. I think there’s still a deep sentimental love of motion picture film. That’s where you start to hear about the sharpness of digital. Then it becomes a matter of maybe the lens can help soften that a bit.

The other thing is the tweaking of the look happening more often in post-production rather than on set. DPs and directors were able to dictate the look and nobody messed with it downstream. Today, with digital, there can be a lot of tweaking in post. I think a lot of people want to put vintage lenses on so that the look is defined on set. We’re in a transition era of people still adjusting to digital and digital moving so fast. Look, 4K is what? Five years old? And suddenly it’s 6K, then 8K, and now it’s 12. That is very interesting.

You mentioned earlier about counting all those Super 35 cameras. But for the past three years, I thought we were migrating to Full Frame. Including Canon. But recently, we saw your C70, RED KOMODO and Blackmagic URSA Mini Pro 12K all coming out within weeks of each other. Is that a trend or just another choice for DPs?

My view is that Super 35 is entrenched globally. It’s got a massive history with an enormous inventory of 35mm format lenses. All of us started our digital saga on Super35. The first Full Frame 36x24mm format cine cameras are only three years old. Then we all jumped on the bandwagon. But there are two worlds. We think Super35 is going to stay rock solid. Full Frame is growing. There’s no question. We felt comfortable to play in both vineyards. For example, in the last year, we brought out the C500 Mark II Full Frame camera, and a few months later, the C300 Mark III Super35 camera, followed by the C70 Super35 camera a few weeks ago.

It’s not unlike the thing we’re facing in still photography, with DSLR and mirrorless cameras. I think that’s Canon’s viewpoint: the world is very big and there are legions of people who appreciate choices. Especially in this new, golden age of digital cinematography. So we produced major new products in both categories during the past twelve months.

I believe I see kind of two simultaneous threads in production. One is the high-end for big budget movies. And then there are also the more affordable cameras like your new C70. It seems that the affordable products are soaring in sales. How do you think it’s going to continue? Will there still be a high-end or is that going to be replaced by the more affordable business model?

I think there will always be a high-end. When you look at the specs that, say, Netflix has written and the way they test all the cameras in their lab, they’ve defined a bar for their originated programs. They’ve set bars on the camera manufacturers. They still do tiering in programming. They do the really high-end shows like “The Crown” but they have documentaries, reality and other things. That’s where you have the spectrum of price-performance with the lenses and cameras that will be there. That said, there’s no question that prices of many cameras are becoming more affordable, I’m still stunned how we packed all that we did into a $5,500 camera. But then you can’t discount competition. There is more digital competition out there now and we all have to be competitive.

The Canon C70 could be a model for many more cameras to come as to form factor and philosophy, not just in Super35, but also in Full Frame, because it has such a user-friendly shape.

Exactly. And there is an awful lot of run and gun type of filming, even in major motion pictures and episodic television. People are shooting in confined spaces and on drones, gimbals and handheld where compactness, size and weight all are very important.

That could be an interesting request for the next generation of Canon RF mount, Full Frame cine lenses. They probably should be small and light and very high performance as well.

Well, if you look at the compact servos that we made, the 18-80 and the 70-200, they were little miracles. I’m passionate about them. 2.65 pounds, 4K, built-in image stabilization, the servo drive built into the lens, also wireless, manual Iris, camera control of iris—all in those tiny little lenses that are 7.2 inches long. For documentaries, nature, sports and reality shows, these are dream lenses. And I think they set the stage for further innovative developments.

And the Canon Cine-Servo 25-250 T2.95 zoom is amazingly versatile.

I bragged for three years about our 20x zoom, the CINE-SERVO 50-1000mm T5.0. That was the technology we spun down for the new, 6.7 pound 25-250. And that includes a built-in 1.5x range extender. Established 10x Super35 zoom lenses typically weighed 16 pounds. It’s a gem.

If we look back at our FDTimes interview last year in Japan, February 2019, a gentleman named Larry Thorpe said, “Lens resolution is bounded by diffraction as the lens aperture is stopped down and by the collective of the multiple optical aberrations as the aperture setting approaches wide open.” Would you please explain.

Sure. All lenses have an issue as you stop down. Diffraction is the great dictator. You progressively lose MTF as you stop down. Then, as you open up the aperture, diffraction sort of moves to the side, it becomes less of an issue. And then you confront the aberrations. There are five monochromatic aberrations. I think you know them: spherical aberration, coma, astigmatism, field curvature and geometric distortion. And there are two chromatic aberrations: lateral and longitudinal. As you open up, you’re fighting the aberrations quite a bit. They become more challenging on wide aperture in all lenses. Lens designers have spent years and years to combat those aberrations, to try and reduce them.

As our optical designers considered the many requests for a new full frame prime lens they carefully considered the ramifications of translating the many artistic expressions they received into optical characteristics. To do this they had to mobilize their accrued experiences and sharpened senses – honed over many years of optical design – with their cultivated optical design technologies. And, the latter brings us to the very latest in optical simulation tools.

We could simulate glass materials, glass geometries, element groupings, et cetera, to fight those aberrations, to lower them. But in getting all of that acumen into our computers and all of the multiple technical details on the different glass materials – our optical designers had acquired a deep familiarity with all of the associate imaging characteristics – and were able to essentially reverse engineer things.

With the Sumire Primes as a new design goal, we could say, “Wait a minute, suppose we don’t want to combat them. Suppose we want to exercise the aberrations themselves to impart a look?” We know the looks that we formerly considered to be nasty and that took away sharpness. But if people are asking for a softening, or smoothing, can we play with each of these aberrations in simulation? Could we try a different footprint and maybe some combinations to create a different sort of look?

Canon in Japan were able to show those simulations to some high-end DPs. When they received enough positive feedback and got certain blessings, they went ahead in building Sumire Primes. We will not reveal which aberrations we played with. That’s our secret sauce. But the essence was to exploit what we formerly always combated as we opened the aperture and then said, “Back off, let’s exploit it”. It’s as simple as that.

That must have driven the optical designers crazy because they have spent entire careers ironing out these aberrations.

Yes. The simulations were performed on Canon’s super computers. They run 24/7. They search for glass materials, combinations of geometries and groupings. You are talking about billions of calculations.

Once we were able to do this in simulation, then had to have terrific consultations with our actual manufacturing people to ask, “If we can do it in computer simulation, can you do it physically?” And that was what became Sumire Primes. They are a product of the most sophisticated simulations and the most sophisticated manufacturing precision to be able to tweak geometries and to implement what the computer predicted. That’s the magic of Sumire.

This article appears in the January 2021 Edition 106 of FDTimes.