An Interview with Sam Nicholson ASC on real-time virtual backgrounds and production in the time of Coronavirus

During this pandemic, how do we shoot on location without flying there? While some of us think green screen backgrounds are about as much fun as having root canal work, what if you could use affordable, consumer electronics, large screen LED TVs and projectors to let the actors interact in real time with their backgrounds on set? You can, and Sam Nicholson explains how.

Sam Nicholson ASC is the founder and CEO of Stargate Studios and an award-winning visual effects supervisor. He and I have known each other for a long time—sharing the thrill of racing to be first to try untried prototypes—including his work with the Blue Herring 36 megapixel ARRI / Lockheed-Martin digital camera the size of a Fiat 500 in the 1990s, demos for Sony F55, Canon C300 and more.

So it was fun when Stephanie Hueter of Blackmagic Design asked whether I’d like to talk to Sam about his latest adventures. I was on the phone a few days later listening to his ideas on keeping productions safe, cost-effective and efficient.

Stargate’s ThruView real-time virtual production system brings backgrounds into the studio without having to be on location. Stargate worked on the HBO’s new series Run. The story follows the characters as they travel across the United States on a train, but production never left the studio in Toronto—except to shoot the background plates in advance.

One of the great things about doing an interview with Sam is that you ask a question and it’s like winding up the Energizer Bunny. He does not want for words.

HBO series Run

Jon Fauer: Please tell us about the story of Run, for people who haven’t seen the show, what you did on it, and go through the technology that made it work.

Sam Nicholson: Run is a great example of the evolution of a production that relied on virtual production for a green light that had to go through all of the necessary steps to convince the studio, producers, director, DP, and everyone else involved, that it was possible. The story itself revolves around two people who get on a train and have an affair. They travel across the United States and unveil a tremendously complex story, but the whole thing occurs in transit. For the whole series, we estimated we would have approximately 300 shots per episode. Across 10 episodes, that’s about 3,000 shots.

The train had a highly reflective interior, with a tremendous amount of glass. We theorized doing it on green screen, but that was both cost-prohibitive and also creatively constraining. Shooting with actors on a green screen for 10 weeks is very difficult—it is like putting on a green blindfold.

As much as we have pre-visualization tools from the past, and things that could give you an idea of what the final scene is going to look like, it also needs to make sense financially. It needs to be an even break from green screen. Ideally it should cost less, take less time and should produce superior results. So, we were trying to solve the “good, fast, cheap” triangle all at once. And we were supported by EOne, Mark Gordon and HBO.

I took a page out of what I did for the engine of the Enterprise back in Star Trek: The Motion Picture. I was still a student at UCLA in the late 1980s, and I had to convince Paramount that I could do it—create a 60-foot high column of light. I built eight feet of it and took it to Paramount Stage 9, swung it out in the middle of the Enterprise and said, “There it is. All I have to do is make it taller.” Bob Wise and Gene Roddenberry looked at it and said, “That looks pretty cool at eight feet. Imagine what it would be like 60 feet high.” Boom. I got the job. And it turned out to be a hell of a job to make it 60 feet high…but that’s all another story.

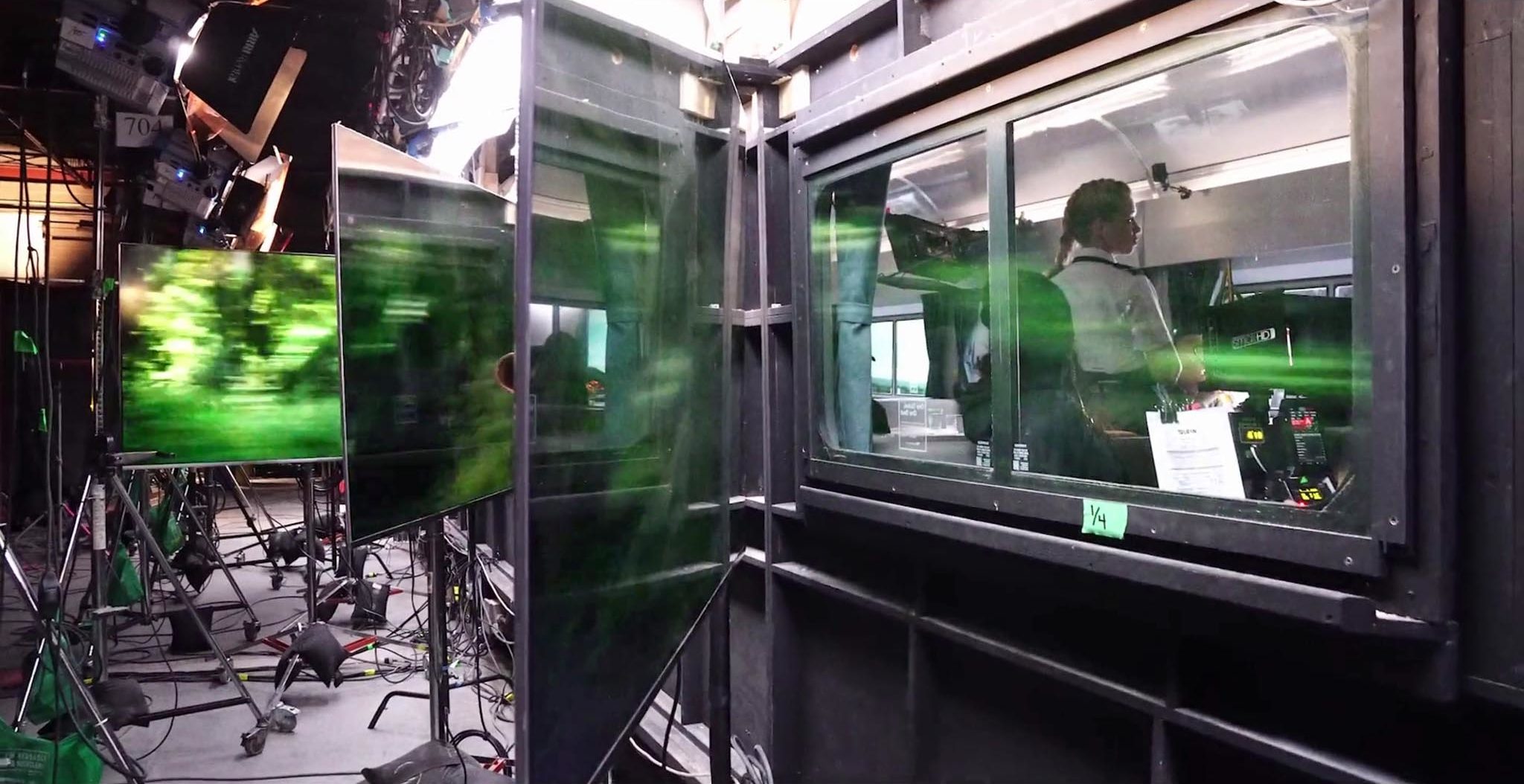

For the train on Run, I decided to build a piece of the set to scale. At our studios, we had four windows and a vestibule (the fifth window) with four little tables and chairs. I showed it to HBO. We allowed them to sit on the train and take a look. We could shoot and test it. I believe about 14 executives came out that day from HBO, EOne and Mark Gordon. We shot plates from the Los Angeles Metro and determined how to shoot plates for the show. We went down to Best Buy and bought several 4K monitors. We had an LED wall there as well, so we could show the comparison between an LED wall at P2.5 and a 4K monitor at full 4K resolution (10 times more resolution) with interactive lighting tied in. When the executives came out and saw the demo, they were convinced and signed us up.

The Digital Age of Film

Going back in time to the beginning of the digital age of film, you have said things got easier and different all of a sudden. Was that between 2005 and 2009?

Yes. I think the transition to the digital era represented moving from a post-production lab—essentially “wait for your dailies to see the images”—to real time, where you could see your image as you were shooting it. Today, virtual production is going through the next evolution of technology. We can now see our visual effects as we’re shooting them. In this way, the creative feedback loop becomes real time. I often say that trying to do visual effects on green screen is very much like trying to learn how to play an instrument and not being able to hear the music. You hit notes, and two weeks later you finally hear the chord. On green screen, you learn at a very slow pace.

Hear the Music

Now suddenly, you can hit the keyboard and hear the music. You can look through the camera and see your composite live, and not as a six-frame delayed previs. It’s really there. With Epic’s nDisplay off-axis rendering, it is now possible to see an absolute finished product in the lens using LED walls and OLED monitors for the backgrounds. This has a tremendous effect on the psychology of everybody on set, because the actors can now see where the Eiffel Tower actually is, rather than imagining it from a laser dot on the screen. Cinematographers can exactly match the lighting between the foreground and the background. The director can block his or her shots by just walking and seeing them. The creative participation involves everyone on set. The key grip can say, “I was just looking through this window and I saw an awesome reflection…come and take a look.” Then the DP goes out, takes a look and says, “What a great shot,” and puts a camera out there.

Green screen, or chroma matting, is not going away by any means. It is a necessary technique, to which we will look back someday as being extremely archaic. As soon as we have depth matting and light field cameras, we will have no need for chrominance matting. Additionally, AI will greatly enhance depth matting, to determine edge definition and spatial dimension using LIDAR. These depth mattes will be tremendously advantageous, as opposed to no matte in post, in order to change the focus or to change the color of the background.

We are still in the middle of a transition here. This is not the end game. The screens are becoming higher frequency which allows us to shoot high speed on them. The lights are becoming controllable to an extent where we can synchronize them with the camera shutter. The camera shutters are promising global synchronicity, or extremely high refresh rates. Therefore, it’s much easier to synchronize your lights, display and camera. And that’s really what we’re going for. But right now, they’re all running wild.

Mountain Climbing with Fingers on the Edge

It’s crazy. Just walk onto any LED set and announce that you want to shoot 120 frames. Everybody will head for the exits. I feel like we’re mountain climbing and we just have our fingers on the edge of this precipice. There’s a whole mountain ahead of us and we’re very gradually getting up that mountain. This is a significant step forward, but you need to have plans in place in case your tenuous finger holds slip a little bit.

Hypothetically, let’s say you’ve been shooting a 24 fps dialogue sequence. Everything’s going great. But then the director says, “I want to shoot through the window at 120 fps. Oh, and by the way, I want to rack focus from the background through the window.” Your screens are going to moiré if they’re LED. Perhaps you forgot to tell the producers they could only go to 48 fps. You want to have motion blur, but the screen is literally flickering at 60 or 120 cycles per second. Unfortunately, rapidly moving objects in front of that screen are going to strobe. When Merritt, the performer in Run, threw her handbag in front of the screen, you could see four handbags. It was not natural motion blur. So we had to go in and add natural motion blur back to all the objects.

Safety Net

One of the advantages of Stargate Studios is that we are a full service production company. We have the capabilities to not only shoot from the beginning to generate the material, generate the 3D assets for onset playback and prep, but if anything goes wrong, we also have the ability to have a safety net ( i.e. to go in and fix it in post at little or no cost to the producer). This is why you really need that safety plan in place.

We did the pilot of Run a year before the series. It wasn’t until 18 months after we had shot the pilot that we went into post and polished the final shots. And that did not become HBO’s problem—we handled it. For instance, in one episode, we delivered 400 shots and 350 of those were final pixels on set with no post production enhancements. If you subtract the purely CG VFX shots, we repaired about five percent. Therefore, having a full-service approach on the entire concept, I think, is very important. Stargate Studios is not simply a preproduction, principal photography or postproduction service. We cover all three roles for any scale of production.

How does the current process differ from your Virtual Backlot with camera tracking?

Well, a lot of the philosophy is the same. We cover things photographically in 360 degrees, as if it was being shot on green screen. The difference is that now we can shoot in real time against emissive screens.

We are interested in whether we take a virtual space—either photographic or rendered—and blend it with real photography to make it seamless. With our Virtual Backlot, we are creating an immersive world in the background—again, either photographic or rendered—in which you can look any direction. You can do any shot: up, down, sideways, two-shot, single, close-up, wide shot, anything. We also capture the move data of the camera in physical space: 6DoF, XYZ, yaw, pitch, roll. Even lens data, focal length, and aperture.

From Green Screen to 40x4K Streaming

Previously, if you knew your depth of field and everything else about a shot, the horsepower (from a computing standpoint) was insufficient to render photo realism in real time. With the Star Wars Underworld project, we proved that to George Lucas. Various shows like Pan Am, with a 400-foot green screen, looked great, but all we could render on set in a 50th of a second was a low poly model. Better than gray scale and okay for editing, but certainly not broadcast or finished quality.

Now 10, even 20, years later, the technology of the graphics cards from Nvidia is GPU based rendering. It’s a single computer that is screamingly fast with multiprocessors that are all coordinated. The Unreal engine software has been a major step forward in terms of real- time rendering and off axis display and remapping.

We had 40 times 4K streaming video to an extreme amount of pixels to make it real on Run. This was made possible by the Blackmagic Design DeckLink 8K Pro cards with hyper quad feed of the 8K streams. Combined with our proprietary tracking, we’ve now made 14 trackers based on the Intel 265, which gives ThruView absolute tracking of every single camera and object on set. Markerless, trackerless, and wireless. Imagine running down a silver tube, which was the train in Run, 150 feet long, with 40 4K screens outside the train windows on either side that are all tracking to where you are, and you have no tracking marks, no wires, and you’re on a Steadicam.

Was that what you showed at Cine Gear last June?

Yes, that was a piece of it. That was one window. Now we have both sides of the train. We can see the reflections of one window off the other. And not to mention that we could do it with Samsung monitors that you could purchase at Best Buy. We just went and bought 40 of them.

What size monitors where they?

82-inch. It was a great business model because it looked fantastic in camera, it was affordable, and it saved the production approximately $100,000 an episode, which is pretty considerable. We were shooting with the Panavision DXL, so we wanted to shoot in 8K. Everything was completed in camera at 8K resolution.

The DP, Matthew Clark, could shoot with the camera and lenses he wanted, the actors could see everything. It was fun sitting on the train as opposed to sitting in a green box. You could watch things go by, you could talk about what’s out there. And the resolution of the monitors were such that you could focus on them.

Even that rack focus you were talking about?

Yes. You can look directly at the monitor and focus on it with no moiré. But it is not for everything. For example, if you have a 70-foot balcony, you’re not going to use an 82-inch monitor. I would say that our approach is display agnostic. We can have any combination at any resolution: LEDs, OLEDs, projectors from Canon and Sony. One size does not fit all. A modular, scalable approach is important. Every production and every scene has its own unique requirements. There will be fabulous $10 million setups like the Mandalorian where you walk in and it’s an immersive environment. But you’re working to the technology at that point, and I think it’s got to be the other way around.

The Paintbrushes are Different every Time

The technology has to work to the production. You shouldn’t have to change everything in your production so you can work with a particular camera. The creative necessity and requirements of the show should dictate the technology configuration. By the definition of production, the tools that we use, i.e. the paint brushes that you pick out to make your particular painting, are going to be different every time. They have to be dependable, they have to be proven, they have to be tested.

Virtual production is now Live Performance

Virtual production is now live performance. The burn rate and the pressure are much higher on a set than in post-production. A 3D artist or a colorist is no longer in a dark room with headphones on, in a perfectly silent, don’t disturb mindset. On set, lights turn on and off, and people are unplugging your computer when you don’t know it. Anything can happen on a set. It’s a rough and tumble world, and you have to be ready for anything.

The AD is standing over your shoulder saying, “We’re going to flip the schedule and can you be up and running in 10 minutes?” And, first team’s on set and the actors’ makeup is melting and “what do you mean the playback’s not working?” Or, “What do you mean you’re not getting tracking on camera C?” I would love to see a colorist at a major facility with a First AD sitting over him or her asking, “How many seconds before you are you ready?”

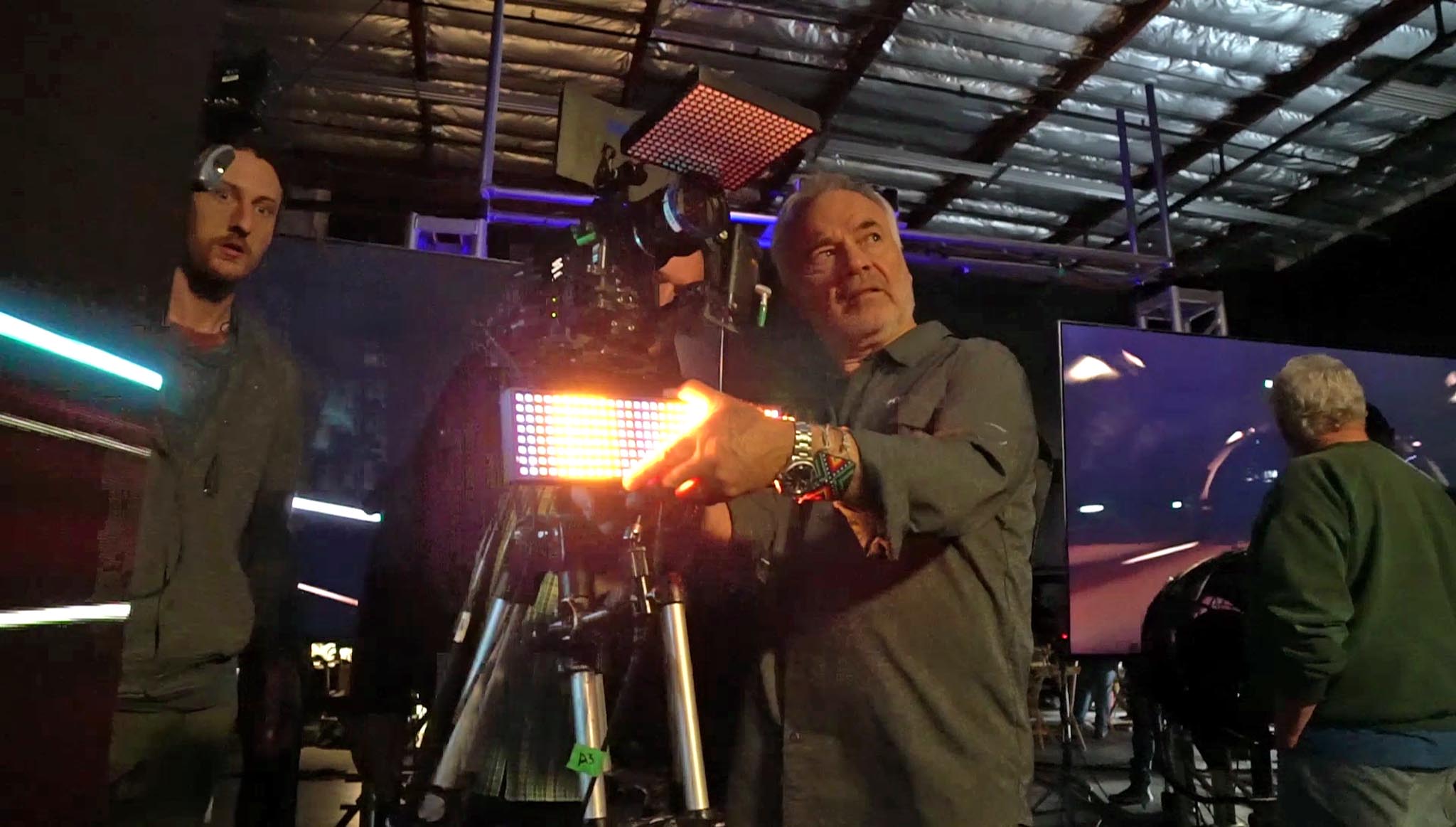

3 DaVinci Resolve Studios, 250 SkyPanels

On set, dynamics require a different mindset, much like that of DITs, who came into play because of the necessity for digital asset management. This is going to open up a whole new career path for many people, such as the on-set colorist. We have three DaVinci Resolve Studio systems complete with DaVinci Resolve Micro Panels that we’re operating on set for Run because we’re adjusting color of the foreground and doing real time compositing.

Our ThruView system allows us to adjust and control all the lights on set: Run had about 250 DMX-controlled ARRI SkyPanels. If you think about a train going into a tunnel, and yellow lights go by, everything has to be synchronized. Part of the ThruView system is the pixel-mapping of proprietary lights that we have built that have true kinetic control, 126 DMX addresses per light, so that you can “ripple” the light.

If you’re in a car and a red bus goes by, there’s red bounce light automatically from that bus. And as you jump downstream to do coverage from your wide shot, you have to be aware that everything still has to maintain the synchronicity. Therefore, you are also editing on set. So DaVinci Resolve Studio has been a key component in terms of playback and color control for us on set, but the operator is probably going to have to be controlling three or four of them at once. This is one of the positions that we can remote off-set to address today’s production concerns.

I can’t stress pre-production enough. Like a theatrical performance, when the curtain opens, is it perfect? Does it play? Five minutes of downtime on set is an eternity.

This is the shift that the visual effects artists must do to be able to handle the pace and the pressures of real time. If it doesn’t work, the shoot continues anyway. Nobody’s going to stop. It’s like a parade and the visual effects people are sprinting in front of it and trying not to get trampled. Production doesn’t stop. If you don’t have your act together, you’re going to see a green screen go up in about 20 seconds. And then, you’re going to get a call from the studio, and you don’t want to get that call.

RED on Run

Live action shoots are subject to so many unpredictable factors. Like temperature. Who would have thought that temperature would change the color of monitors? For the Run pilot, we were in Toronto in the winter on an unheated set. For the background plates on Run, we rigged two train cars with multiple cameras and travelled throughout the United States. We did two separate shoots on the train. For the pilot, we did a shorter run as a proof of concept from New York to Chicago and it worked well. We shot with four RED MONSTROs in the daylight and two Sony VENICE cameras at night. More than 200 terabytes of original camera data were stored and backed up during the shoot using high-speed SSDs and portable RAID arrays from SanDisk and Western Digital. We played the 8K footage back on set with the help of Blackmagic Design and Nvidia in our ThruView system, with one 75-foot train car for the pilot and 20 monitors. We shot at a rate of about eight pages a day on the train. After HBO green-lit the series, we took a train across the United States for the rest of the season.

We had our own train cars. We mounted cameras throughout the caboose and a sleeper. It was one of the most pleasant shoots I’ve ever been on. We sat in big overstuffed chairs and watched the world go by. You could get on the radio in beautiful locations and say, “Roll cameras!” With so much original 8K material, it was about data management and how you reduce it to something the director, Kate Dennis in this case, could view and make decisions getting everybody on the same page with planning.

The principal photography production team at Stargate Studios is great. We generally shoot our own plates, and we make sure they’re stable, high resolution HDR. The plates should be perfect. They can’t have shake in them because you’re not going to do post-stabilization. It’s real-time playback. You have to be very careful about what you ingest in a real-time system.

For Run, we shot our own plates, organized them, put them forth, and Kate made her selects. We arrived a few months later on set, but at the very last minute, eOne decided they wanted to feature two train cars. We had to double everything about a month before the shoot. The new production design featured 40 train windows which in turn equaled 40 times 4K displays.

Then we’re on set, and it’s a marathon. You’re in for 10 to 12 weeks of shooting with everything that comes at you from different directors and a lot of variables, split units, pickups. Despite the planning, unpredictable things happen. There are schedule changes, where the producers decide to change the set over to a new set, so you have to disassemble all 40 times 4K systems with five miles of cable, and by 8:00 the next morning, reassemble it for a different train.

Depending on the complexity, two to four people can manage the system. That’s all the lights, monitors, tracking, and playback. This reduces the number of people you need on set, which is important going forward. A lot of jobs can be remote, like color correction, tracking, or lighting control.

The business model going forward, I think, is very important. When done properly, virtual production can be a very powerful tool to reduce the crew footprint and get us back to shooting anywhere in the world without having to be there. Or doing big crowd scenes without actual big crowds. Or avoiding airports or worrying about your stars and where they’re going to stay abroad, i.e. which hotel in Bulgaria and is it safe? They can be in a pristine, sterile environment that is completely safe.

Tracking

Explain to us how tracking worked on Run.

On Run, we tried many different types of tracking. We tried inside-out tracking, outside-in tracking, we tried infrared tracking, targeted tracking. We did the pilot with infrared, specifically the Vive system, which is pretty accurate and affordable on multiple cameras.

Can you backtrack and explain tracking and why it’s necessary?

Virtual production is based on real-time camera and lens tracking, which applies to whatever display you’re shooting. It means that the display knows where the camera is and the camera knows where the display is, what is on the display, and it recalculates based on the camera position. So effectively, it turns a monitor into a piece of glass, like a window, and instead of having the image stuck on the plane of the monitor, the image actually exists at infinity. It is properly in depth.

You can lean in and see more around the edges of the monitor. You can back up and see less, you can look right or look left. That’s why we call it ThruView, as it takes any display and turns it into a window to another reality.

Tracking becomes an essential part of that. There are many different types of tracking. “Inside-out” tracking is from the camera. The camera sensor, that you’re tracking with, is looking out. With “outside-in” tracking, as you’ve seen with MOCAP, the sensor is outside tracking a number of cameras looking at a reflective surface. The camera doesn’t have any intelligence on it. The intelligence is outside.

They’re both very viable, but have weak points. You need to decide how you want to shoot a particular show in order to determine the appropriate type of tracking for the production. In a perfect scenario, like a newsroom, you can have targets up on the ceiling, and the cameras are in very predictable places. The cameras are on pedestals, and they’re just roaming around under these targets. That is a very stable tracking scenario. But in dramatic filmmaking, that’s probably not going to happen.

We realized we had to be on a Steadicam that could run down the length of a 150-foot-long train (two train cars) and go through the vestibules where it will completely lose information. Since it’s moving, you have to run down the cars while all 40 monitors are adjusted in real time to the perspective of the camera’s location. You need to be able to run over, look out a window, back up, see the vanishing point, run down the train, tilt the camera. So the question is: can your tracker live through that?

We tried it with infrared, but the world kept flipping upside-down and we couldn’t figure out why. It turned out that the microphone boom held over the camera would periodically obscure the IR transmitters. Since it’s infrared and inside a reflective train, the wavelengths are bouncing around all over the place, picking up the next strongest signal, which is a window. And all of the sudden, the world doesn’t work.

We couldn’t put up targets or reflective markers inside the train, nor could we have a bunch of cables coming off a Steadicam. The solution had to be marker-less and wireless. Fortunately, Intel came out with a T265 sensor, which is both inertial and optical, and creates a point cloud. It worked.

We wrote the code for building new trackers based on Intel’s technology. We constructed it so it could fit on the back of a camera, like a FIZ (Focus Iris Zoom wireless control). It’s wireless, it uses Wi-Fi, and is accurate, especially for XYZ. All you need is three axes, so we limited the data to exactly what we needed. In turn, it was wireless, marker-less and gave us the speed and accuracy for a Steadicam.

All of this is now improving with next-gen thinking, but for us it was affordable and effective enough that we could put one on every camera (and have backups). There’s always a financial model to this too. If you have a $100,000 tracking system, it costs more than the camera. The system therefore has to fit the creative and technical requirements while meeting the financial and practical requirements on set.

Since we didn’t have them, we built them. Necessity is the mother of invention. We did the same with lighting. We built our own custom lights for the show, and we also interfaced to all the ARRI SkyPanels and DMX controllable lights. We wrote a lot of software that didn’t exist to tie into the unreal engine and to have a seamless crossover from the Blackmagic Design system into the Unreal Engine for redistribution to 40 4K monitors. We then had to write some very specific code to remap the monitors to the tracker. For example, if camera “A” was looking at monitors 1 through 10 and camera “B” was looking at monitors 11 through 20, we needed to be able to assign the tracker to the individual displays.

Blackmagic Design Products

How is the system connected together? I understand you worked with DeckLink 8K Pro capture and playback cards, DaVinci Resolve Studio, DaVinci Resolve Micro Panels, Smart Videohub 12G routers, UltraStudio 4K Extreme capture and playback device, a Teranex AV standards converter, an array of Micro and Mini Converters, as well as an ATEM Constellation 8K switcher.

On the exterior of the 150-foot-long set, there were 40 4K monitors lined up right down the line of the train, numbered A1, A2, etc. There were three DaVinci Resolve Studios with DaVinci Resolve Micro Panels for color grading. Multiple Unreal engines tracked and redistributed all the video signals and lighting control. We had eight trackers for four cameras, which provided complete redundancy. The tracking, lighting, playback control and distribution were all hot-rodded PCs with Nvidia cards in them running Unreal Engine and DaVinci Resolve Studio. It was scalable. All of the hardware was assembled on camera carts so it could be exterior, interior, wherever we wanted to shoot.

Where are the plates? Are they in the PCs themselves?

They’re inside and outside. We have a great relationship with SanDisk and Western Digital. So, we could bring all 200 terabytes of storage on set in SSDs and portable RAID arrays. We often needed to change setups and scenes very quickly. The SanDisk 2 TB SSDs are about the fastest scene holders I can think of. We had multiple SSDs for every day’s work. We could quickly pop them in and have all the monitors change to a new scene since we never know what might happen on set.

And then the DeckLink 8K Pro feeds what?

The DeckLink 8K Pro feeds it to the Unreal Engine, and then it’s split up and redistributed by the Smart Videohub 12G router across 40 mounted monitors outside the train windows. The 8K signal is chopped up and redistributed over four monitors (in this case), and you do that times 10. With virtual projection, which is required for off-axis display, you put your flat data and your 3D data into the engine. The engine then mixes it up, splits it and cuts it into all the different feeds, and sends it out synchronized to all the monitors. In addition, we wrote the code to adjust the perspective on all the monitors simultaneously. This gave us the capability to step inside the train and adjust the perspective of all 40 monitors simultaneously. A scene does not just come up magically with the perfect perspective. We have to be able to adjust the horizon, not only globally across all the monitors, but individually.

And these monitors are all rotating. If you’re shooting one way down the train, they rotate 45 degrees one way. If you’re doing a flat two shot, they’re flat. You need to be able to recalculate the offset in physical space between the monitor and the lens of the camera. Normally speaking, you can take a tracker, touch it to the surface of your screen and are at the same place—zero point. But if your camera is inside the train and your monitors are outside the train, then you can’t physically get to them. This is part of the tricky programming that we’ve done to optically calibrate the screens—the ability to understand where a monitor is without touching it.

Tell us about the cameras and lenses you used for the plates.

We had a lot of suction cups. These are great if you ever need to shoot out the window of any vehicle. This was literally planes, trains, and automobiles. For lenses, we had 180 degree rectilinear lenses on RED HELIUM and Sony VENICE cameras shooting in 8K and 6K.

Canon 8-15 mm lenses are fantastic. They are sharp edge-to-edge. The principle is if you’re going to shoot for virtual, you need to be extremely stable, extremely wide, and extremely high definition, because you’re going to subsample it. Imagine you’re going to shoot the actual scene with a 50mm out one window of the train. You’re seeing maybe one-tenth of the original data.

Therefore, you need the highest resolution you can get with a very low signal-to-noise ratio. This is why we used the Sony VENICE Rialto rigs at night and REDs during the day. You can combine these, but as a general principle, they have to be shot right. If you just latch a camera to a car, good luck. It’s going to be shaky and crazy when you get on set.

What lenses did you use on set with the Panavision DXL?

We used the Panavision PVintage Prime lenses (Panavision 1976 vintage Ultra Speeds, updated with modern housings).

DaVinci Resolve Studio

Explain why you had to do color correcting in real time with DaVinci Resolve Studio.

We shot all the plates in focus so we could match the focus to what we shot on set. As a visual effects supervisor, the first thing I do is look at it and say, what’s wrong with this picture? Why doesn’t it look real? Well the blacks are too black: push it back, give it more atmospheric perspective, slip the focus. All those creative things that we do in compositing you now have to do in real-time on the set. So, there is no magic button that you push that says, “real”. I wish there was a “real” button where all the relationships between the foreground, background, focus and color would just drop in.

Getting those things perfect is why we sometimes do up to 70 revisions on a simple green screen composite. Now, we are doing that in real-time. So, you need an incredibly responsive tool that can quickly adjust perspective, match focus and adjust color in real-time. It has to be extremely intuitive. When the director says, “I know I picked those plates, but I don’t really like what I see. Do you have anything else?” you have to be able to re-edit your material on the fly. In the effects page of Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve Studio, you can do all of the things you would do in composite, such as correct lens distortion, defocus, etc. You can adjust certain things to make the image look real, all in real-time. So, it’s essentially taking all the control we normally have in post-production but moving them onto the set.

Are the background plates going live from the SSD, through DaVinci Resolve Studio, and then to the monitors while they are shot in real time on set?

They are graded in real-time. You transfer footage to a local drive, which is ideally your SSD. If you need to, in an extreme sense, you’d take a USB-C connected drive, plug it in to the computer and drop it onto the timeline. In this case,you’re literally playing back off an external drive in 8K to the set. When you’re doing live color, the director or DP might say, “I want the yellow lights to be brighter when we go in the tunnel”, so you have to adjust all the lights on set as well as the lights in playback. Then the director might say, “We’re in the tunnel too long.” So, you have to edit all the video streams, shorten them by 15 seconds or so enabling you to exit the tunnel sooner. And then, maybe, when they want to drop downstream and do pickups, you need to be able to jump forward in the data stream to keep everything in sync. For example when a house goes by in the wide shot, the same house goes by in the close-up shot out of sequence. It has to maintain synchronicity.

So it’s a trial by fire for a colorist. We are actually working on some very interesting things with Blackmagic in the category of real-time visual mixing. These are all real-time tools.

Lighting

Is the DMX tied into this as well?

The DMX is a separate system, which we pixel-map using a combination of MadMapper and custom tools. We accurately pixel-map all of the lights and blend them into the Unreal data stream. As a yellow light goes by in the playback, it’s been remapped into the engine, so that the yellow video feed automatically activates every single one of the lights all the way down a 150-foot-long set. They are also individually addressable, in case the DP wants more pop on one specific light. You need to have that type of control, and it has to be fast. Many times, you’re rolling and still trying to adjust the lights. It’s definitely a theatrical type of experience. It’s moving a very complex set of tools we have carefully adjusted in post for many years into a real time orchestrated playback.

Did you remap the ARRI SkyPanels?

Yes, all of them. We worked closely with ARRI, since it’s not just about letting the lights sit still at 3,600 or 5,600 Kelvin. This is kinetic light. It moves. These lights are exercising down to zero and back all the time. Three-quarters of the lights are out at any moment. The concept is really over-lighting the set by 200% or 300% and then being prepared for anything. Your set has to literally go from night to daylight kinetically.

If you can do that, the savings are enormous. You can shoot very fast if you are able to put up a different plate and the lights adjust automatically to that look. It takes a little more rehearsal and set-up time. One of the major advantages of virtual production, when done properly, is the ability to change an entire set and the entire lighting configuration within minutes.

Train Interior

I’m looking at a photo of the interior of the train with a camera. It looks like you were probably pretty wide open on a lot of the shots?

Yes. Matthew Clark, the DP, wanted a relatively shallow depth of field, yet wanted the ability focus directly outside the windows to the landscape. Kate Dennis, the director, wanted to be able to go right up to a window and look all the way down the track. The inside of the train is highly reflective. That was part of the design. Once we decided to do this live, the production designer said, “Great. We can use all these reflective objects inside: silver, translucent, refractive, reflective.” Everything you avoid on green screen. There was no place to hide tracking marks in the train set. It was impossible to use infrared tracking because of excessive light bounce. We put multiple Wi-Fi repeaters up all the way down the outside of the train because there was so much Wi-Fi traffic on the set with video and sound. Everyone was fighting for Wi-Fi space.

A set is a very dense Wi-Fi network. We tried magnetic tracking and any other types of tracking you can think of. The problem with any type of radio or magnetic frequency is metal objects confuse it. Reflective objects confuse infrared, and metal objects confuse transmission. Targets are ugly, and they have to be removed. You can’t have wires. All these things are specific to shooting in a real-world production environment.

One of our challenges was the camera crew was not used to point cloud tracking. When the camera wasn’t rolling, the camera operators put the camera on the floor—most of the time, out of the way, even under a table. But then, our point cloud trackers went to hell. Our trackers build intelligence during the shot and become more accurate as the shot develops. It literally learns the environment. So, once the camera is under the table, you blind it, making it lose intelligence very quickly. So we had to design a system in which we could take the camera off and keep it pointing at the world enough so that it did not lose the point cloud reference.

Production in the Time of Coronavirus

Your next adventure could be Son of Easy Rider in a studio?

Yes! In the current COVID-19 lock-down, there are a lot of questions concerning how virtual production can help get us back on track. How can we create an insurable, predictable, production environment model going forward?

Can we create a safer, less restrictive scenario than sending the actors and crew through airports and hotels? Can we remove the variables of traveling halfway around the world from the production formula? How can we protect the health of our actors and shooting crew on location? Virtual production offers many solutions to these questions and more because it is safer and more effective to bring the world to the actors than bring the actors to the world. We are all inventing a new paradigm for the future of global production.

A second unit can go out like Alfred Hitchcock did. They can shoot all over the world and pick up all your action scenes. Then can then come back with your principles and recreate the event in virtual production. You have the best of both worlds.

Whether it’s real-time or post-augmentation, they both can play a very serious role in getting production back on its feet. Stargate’s Virtual Backlot Library, which we have developed over 30 years, allows us to virtually shoot almost anywhere in the world. You can shoot a scene in London, New York, Washington, DC. Grey’s Anatomy takes place in Seattle, but production never went there. Or you have shows like Ugly Betty for ABC that never had to go to New York.

A show like Las Vegas didn’t have to go to Las Vegas. At this point, it’s a lot easier to be in a virtual casino than it is to be in a real one. We’re not talking about replacing reality by any means. This is a new tool to imagine tomorrow, which can help us get to the other side of the crisis. Virtual production is capable of combining the real world and the virtual world.

ThruView works end-to-end for virtual production. We offer the assets up front in pre-production and follow them through to final delivery.

We create a complete picture from pre-production through post. I think all of the large studios including Disney, Amazon, Netflix, ABC, and NBC are examining how to reinvigorate their production pipelines. Virtual production will play an an essential role in this new production approach.

Great. What are we waiting for?

There is no time like the present to reimagine the future of production. We have the experience and the tools to get there. The entire global content creation business is ready for a significant step forward. We are proud to be part of the community, not only trying to solve our current challenges but hopefully step into the future of production.

I’m really excited about it because an opportunity for virtual production has not presented itself to this extent in our lifetimes.