Why are we circling the yacht harbor in Herzliyah, Israel, a town just north of Tel Aviv that looks like Silicon Valley? Nicol Verheem, founder of Teradek and CEO of Creative Solutions, has something to say about that.

On November 9, 2018. Amimon Inc. was acquired by The Vitec Group plc. Amimon is now integrated into Vitec’s Creative Solutions division. Creative Solutions, with headquarters in Southern California, comprises Teradek, SmallHD, Wooden Camera, Paralinx, Rycote—and now Amimon.

If you work with wireless video, chances are that an Amimon chipset is inside. It’s somewhat like computers having the label “Intel Inside.” Amimon designs and provides the proprietary chips and circuits inside most of the wireless products from Teradek, Paralinx and SmallHD, as well as ARRI and other companies. Teradek and Amimon have been working together closely since 2012. Amimon’s technology paved the way for user-friendly and reliable wireless systems that “cut the cables” between camera, video village and video monitors on set. It began as a way to monitor complex camera moves, Steadicam or handheld scenes—but has grown to the point where wireless video is now an expected and essential ingredient of most productions.

Amimon was founded in 2004 by Dr. Zvi Reznic, Prof. Meir Feder and Noam Geri to provide instantaneous and visually lossless video transmission over the freely available unlicensed radio spectrum. This technology was originally aimed at consumers, essentially to replace HDMI cables by wirelessly connecting comvideo sources to a TV. But by 2012, the rapid growth of mobile devices and internet-equipped TVs meant that this was no longer so important. Televisions could stream directly from the internet. So, Amimon needed new outlets for its unique technology. Aha, the film industry was an ideal opportunity for a reliable, accurate, and delay-free video link. Today it is nearly impossible to work on a feature, commercial or episodic television production that is not using wireless video with Amimon inside.

The first CEO was Joav Nissan-Cohen. He was followed by Ram Ofir. And now, Nicol Verheem is CEO. Nicol is also CEO of Creative Solutions, and was the original founder of Teradek. The Teradek side of this story goes back to 2010, when it became one of the first companies to release an affordable way to view on-set HD video wirelessly. But camera crews complained about the latency (video delay) from these early CUBE systems because CUBE used H.264 WiFi technology. Fortunately, Nicol had already fallen in love with the cinema industry, and he didn’t want to give up. He and his team identified the technology best suited to providing zero-delay wireless video for motion picture and television productions. That technology was from Amimon.

The result was the Teradek Bolt wireless video transmitter/receiver system that they launched in 2012. At that time, the majority of camera crews were still running cables across the set. The Teradek Bolt and Paralinx Arrow untethered cameras and changed everything. Steadicam operators were now free to do 360-degree shots without a cable wrangler. Dolly grips didn’t have to worry about running over cables. Cinematographers could shoot handheld without seeing wires in the shot. It’s not an exaggeration to say that wireless video was an important part of the technology for drones and gimbals to offer new ways of covering a scene.

All these things were made possible with Amimon’s proprietary silicon chips and software that sends uncompressed video over a robust MIMO (multiple input / multiple output) link. That means there’s less than 1 millisecond delay in viewing the camera’s video output across the set. It’s a sophisticated, patented process that utilizes the full bandwidth of a WiFi channel very effectively, even if the RF conditions change rapidly all the time. The system can also dynamically and seamlessly switch between different RF frequencies in between video frames, making it extremely reliable even in situations where there is RF interference.

Amimon R&D will continue to develop new technology with an even greater focus on the professional cinema and video markets. The team in Tel Aviv will be led by Dr. Zvi Reznec, Founder and CTO, and Tal Keren-Zvi, General Manager. They are both staying on with the company. Uri Kanonich, who has been with Amimon since 2006, continues as VP of Sales & Marketing.

Nicol Verheem gives Uri Kanonich “one half of the credit for the success that is Teradek, Paralinx and Amimon. We learned about Amimon at a consumer trade show. We tried to use of the shelf products, but Amimon sent Uri to visit us in Irvine to discuss the technology in depth. We launched the BOLT a few months later.”

Amimon’s facility in Israel will become a dedicated research and design center for all of Creative Solutions. A benefit of this acquisition is that it should enable the Product, R&D and Engineering Teams to work together intuitively and drive innovation even faster—resulting in rapid development of useful new tools for filmmakers. Currently, Creative Solutions wireless video products are 1080p/60, but certainly we can look forward to more-K in the future. Read on.

Top Sheet (Business Summary)

The business of this business is quite interesting. Someday, Amimon’s acquisition by Vitec could be the subject of a successful case study in business school. And that is why it’s covered in depth in the pages that follow. Like a good screenplay, there is conflict, struggle against obstacles, determination to reach a goal, and the promise of a bright tomorrow.

A few industry wags wagged their heads in wonder about the deal, perhaps with a mixture of Schadenfreude and envy. They asked, “How could Vitec have paid $55 million for a company that lost money last year?” That was quickly followed by, “Uh-oh, will Amimon become a monopoly and choke off our supply of wireless video products that we buy from them or Teradek?”

Those questions and more are answered in the interviews we pursued. Spoiler alert: it’s a wild ride, but there is result, reward and reassurance. I have shortened the interviews from several hundred pages of notes and transcripts. The dialog has been edited for flow and readability but I did not alter the intent. Thanks to Tal and Uri, Nicol and Zvi for their comments.

Reading financial reports and industry reporting only tells part of the story. The official announcement reveals numbers and aspirations. The journalism views it from a different perch. If we were preparing a movie, this page would be the producer’s Top Shot, an overview of the estimated budget. The real story comes in the next pages as a documentary and behind the scenes look, in-depth view of the company, the people and the tech.

ACQUISITION OF AMIMON INC.

Here’s an edited summary of the official Vitec Group plc announcement. You can read the full text online (vitecgroup.com). Vitec is a publicly traded company (VTC) on the London Stock Exchange. The following is not an offering.

The Vitec Group plc (“Vitec” or the “Group”) is pleased to announce that it has acquired Amimon Inc., consisting primarily of its Israeli subsidiary Amimon Limited (together “Amimon”).

Acquisition and integration of Amimon

Vitec acquired Amimon on 8 November 2018 for $55.0 million (£42.3 million) in cash, with an expected total investment of $59.9 million (£46.1 million) on a cash / debt free basis, including employee retention, deal and integration costs. The total investment will be funded from Vitec’s committed bank facilities.

Established in 2004, Amimon operates primarily from its R&D centre in Israel, where the majority of its 60 employees are based. Vitec will integrate Amimon into its Creative Solutions Division. Amimon brings extensive software, chipset design and electronics hardware development expertise, and opens up growth opportunities to develop innovative new products for adjacent markets. Amimon’s Israel facility will primarily become an R&D centre of excellence for Creative Solutions.

Financial aspects of the acquisition

Amimon reported consolidated audited results for the year to 31 December 2017 of $18.6 million (£14.4 million) revenue and reported an operating loss of $0.7 million (£0.5 million). Gross assets were $10.5 million (£7.8 million) at 31 December 2017. For the nine months to September 2018, revenue was $13.4 million (£9.9 million) and EBITDA was $0.8 million (£0.6 million).

Stephen Bird, Group Chief Executive of Vitec, commented, “Vitec is the natural home for Amimon and I am really delighted to welcome this talented team of engineers to the Group. They bring exclusive software and hardware expertise that will add real value to our customers and our shareholders.”

Analysis

Two days after the acquisition, the Israeli business daily Globes, (en.globes.co) wrote, “Vitec buys Israeli video transmission solutions co Amimon. The acquisition price is $55 million in cash, slightly more than the $53.6 million Amimon has raised since it was founded in 2004.”

The financials alone do not tell the story. Globe’s reporting explains a bit more. $53.6 million had been invested in the past by Venture Capitalists to nurture the company’s technology and patents to where they are today.

So, there’s much more to this journey than pondering EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Earnings, Tax, Depreciation and Amortization.) The actual wisdom behind the acquisition, the real behind-the-scenes story, and the reason why Amimon is such a valuable company despite having lost money—that story unfolds on the next pages.

Cast of Characters

- Amimon headquarters north of Tel Aviv

- Marius van der Waat, COO and Nicol Verheem, CEO

- Tal Keren-Zvi, General Manager

- Uri Kanonich, VP of Marketing

- Uri Kanonich, Tal Keren-Zvi and Nicol Verheem with Amimon patents.

- Teradek Bolt Transmitter, Amimon Inside.

- Teradek Bolt Receiver, Amimon Inside.

- Creative Solutions, Teradek and Vitec products surrounding camera.

Nicol Verheem on the Acquisition

- Amimon headquarters north of Tel Aviv

- Teradek headquarters in Irvine, CA

“We fell in love with the Amimon technology because it is really special and uniquely suited to the motion picture market with its mission-critical requirement of no delay, high quality and high reliability wireless video.”

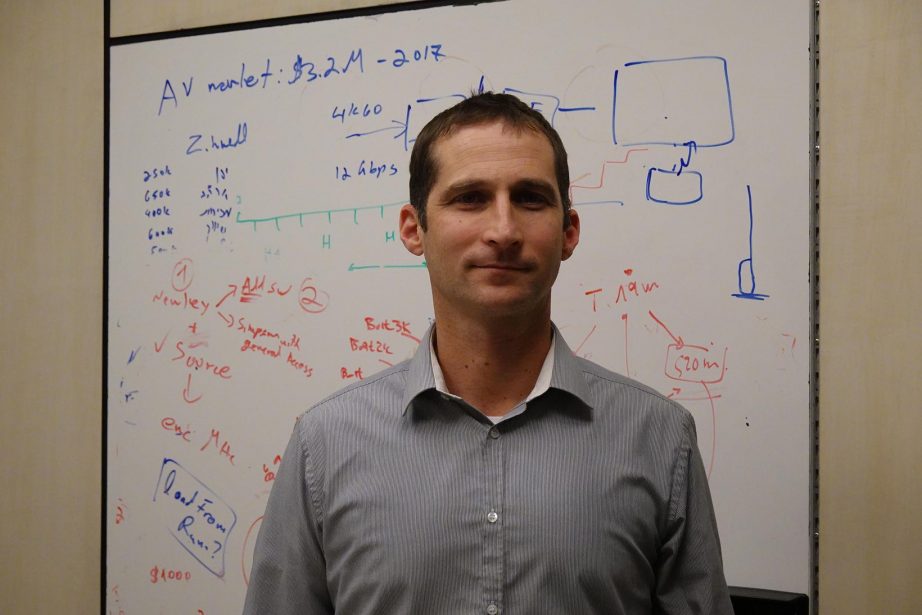

Nicol Verheem, seen here at Amimon, is the Founder of Teradek, CEO of Creative Solutions and now CEO of Amimon as well.

JON FAUER: Nicol, now that we are sitting in a conference room in Ra’annah, thousands of miles from your office, I hope you’ll explain why you acquired Amimon?

NICOL VERHEEM: Creative Solutions is one of Vitec’s three divisions. Amimon technology will be applied across all the Vitec Creative Solutions brands, so it’s equally applicable to Teradek, Paralinx, SmallHD and even to Wooden Camera.

Teradek is one of the companies in the Creative Solutions group. We are known for our wireless video systems. The technology inside Teradek wireless video receivers and transmitters, is the technology developed by Amimon. Their technology is unparalleled. It’s incredibly insightful, novel, positioned to take on all the problems of wireless video. Amimon spent many years and tens of millions of dollars developing their wireless video system.

When was Amimon founded?

Dr. Zvi Reznic was the original founder of Amimon in 2004 with two colleagues. Some of the team have been with Amimon for a long time. Others came more recently. There were periods of growth, raising money from venture capital for expansion, then not being as successful and scaling back. We helped Amimon focus on the pro market in 2012.

Remind me, when did you start Teradek?

In January 2008. We were acquired by Vitec in late 2013.

And in this chronology, where does Creative Solutions fit in?

Creative Solutions has really evolved by adding a number of creative people over the years. Some joined us through acquisitions. The common thing was that they had worked on motion picture sets, on high-end feature films, commercial, documentaries and independent projects.

We have people like Greg Smokler from Paralinx, Ryan Schorman from Wooden Camera and Dale Backus from SmallHD. They were actually all shooters first, that then started to develop products based on that experience. These guys saw opportunities. Then they helped us identify gaps in the tools and develop products to address these needs.

They help shape what the product looks like based on their experience in actual productions. With Amimon joining us, we now have a huge workforce of very technical talent, with Marius van der Watt, our COO, electronic engineers like myself, or algorithm guys like Zvi, who can now build the products to truly match what the industry wants.

Let me explain the most important rationale for the acquisition. It boils down to serving an industry that really benefits from wireless video. When we started doing this, the industry mostly wasn’t using wireless video. It was using coax cables with BNC connectors. We saw a real need. We thought we could add value to this industry and we keep on innovating this product to make it better. It was a decisive moment when we thought this could be our future. We’ve been working at this tirelessly for the last 10 years now. That’s the story of Teradek.

Along the way, we’ve done wired video. We’ve done wireless video. We’ve done wireless over Wi-Fi, over cellular, over bonded cellular, and over Amimon’s proprietary technology. They all have different operations. We fell in love with the Amimon technology because it is really special and uniquely suited to the motion picture market with its a mission-critical requirement of no delay, high quality and high reliability wireless video.

There were a number of additional factors influencing the acquisition. We asked ourselves, “Can we ensure a continued supply?” Also, “Will this technology scale and adapt to what we all see as the future, 4K for example?”

“We want to build an ecosystem of accessories that surrounds the camera, that extends its capabilities, but in a way that’s very carefully thought out and crafted to be very elegant, with fewer connectors and cables and fewer failure points because of poor design.”

Teradek was using the technology but was not controlling it and that was somewhat of a concern. But that’s pretty par for the course. We are a systems company, we end up depending on other people to provide some of the underlying fundamental technology, just as Apple relies on suppliers in making the iPad. But you always want to make sure that there’s a reasonable comfort level in the continuation of supply or access to the technology.

How do you ensure that?

Normally, you would have a supply agreement before you launch a product. You say, “We want a supply agreement that you will keep things at this price, and you will keep availability to us for this long.”

Amimon seemed kind of mysterious to many of us in the industry. At trade shows, it wasn’t clear if they were a competitor of yours or a supplier.

At one point, it was secretive and we actually were in competition on some products. But now, we are all on the same team.

That must have been another incentive for the acquisition.

We looked at Amimon with a very fond respect and admiration for quite some time, but also with some frustration. There have always been some challenges with their ability to focus on what we believed was the best possible application for the technology. If you go all the way back, you’ll see that they had a really fantastic idea 14 or 15 years ago. They raised good money on the premise and promise of this idea, started developing technology, built chips, and went after the consumer market. Unfortunately that was a mistake because what the consumer market actually required was not superb video quality and incredibly low delay and incredibly unparalleled robustness of the signal. The consumer industry just required more interoperability.

So, using something like Wi-Fi is far more attractive to the consumer than the proprietary link that Amimon was proposing. Plus consumers were more interested in a product that was less expensive. It was OK if it had slightly lower reliability or lower video quality or a small delay. But Amimon began as a company focused on consumer technology.

To do what? To transmit how?

Their plan was to replace every HDMI cable with a wireless link.

Like from a camera to a monitor?

Not that one. They were thinking about the cable from your DVR, Xbox or DVD player to your home TV set that was sitting in your living room. That’s essentially what an HDMI cable was meant for.

Amimon’s zero delay did have a clear benefit for gaming. You don’t want a delay from the Xbox to your TV. But for the rest of us, we don’t really care if the cable box is delayed by a few milliseconds. But, to make matters worse for Amimon’s business plan, almost all consumer TV sets became smart TVs. Netflix, Roku, Apple TV and other streaming players were built right into the TV, which was at odds with the Amimon concept. So, it wasn’t really that appealing from a consumer’s point of view.

Was it expensive for consumers?

It was on the expensive side. Some of those products are still floating around, really just trying to be wireless HDMI. There were a few different commercial names. It had great video quality. It was reliable. It had zero delay. But it had a relatively short range and it was packaged into a big plastic box that fit on your mantelpiece or in a conference room—but not suited for a film set or location.

And so, in 2012, Teradek, Paralinx and Amimon started talking because we realized that their video modem was truly unique. We recognized the huge opportunities in taking this zero-delay technology and applying it in professional applications. Amimon came back to us and agreed to start making components to help us address the specifics of our professional market. And neither of us have looked back since then. We came out with the Teradek Bolt that quickly became the defacto standard in wireless video.

Let me come back to your original question. Why would Vitec’s Creative Solutions acquire Amimon? We already had a successful relationship with them. They were our largest supplier and we were their largest customer. Why go and buy your own supplier?

Well, the problem was that Amimon still had the distraction of trying to be successful in the consumer space, whether that was in a living room, or more recently with consumer drones. They’re a Venture Capital backed company, so they were always under pressure to find the next big thing and be a runaway hit. Plus, they ended up in a pickle with some of their customers taking the technology and then applying it in ways that were not really anticipated, appropriate and in some cases, it was flat out illegal.

“That’s not just an opportunity, but almost a responsibility to clean this mess up, to work with the camera manufacturers to get to a system where we retain modularity and options but also have something of a standard.”

Amimon just didn’t have the means to really address this. The result was a very complicated market with official adopters of their technology, their own brand of technology, and then unofficial people inappropriately also using this technology. They found themselves all bound up in this bowl of spaghetti that they simply couldn’t resolve it. It was a concern to all of us. That’s when we looked into joining forces to refocus the business, take this technology, and apply it purely to the professional industries. But it’s not only cinema. We’ll also expand in broadcast and the professional health care companies they already support (with endoscopic products) and one or two select security projects.

Life on set became too complicated.

Taking a step back, we’ve had this discussion before: I think life on set became too complicated, for the camera operator, the first AC and the camera crew, when there was this explosion of camera accessories kicked off by the digital revolution started by RED and Canon and later everybody else.

There are too many devices that go on a camera. Their design is completely agnostic of the existence of any other camera accessory. Most of them has a different power cable with different power requirements. There are multiple video cables. Trying to mount all of these little boxes in the appropriate spot on the camera becomes quite silly. It’s a running joke in our company: people send us funny pictures crying out that somewhere in there is a camera and beneath the ball of wires. Generally, you can see a mattebox on one end and hopefully you see an Anton Bauer battery on the back, and an OConnor head at the bottom. But the camera could be a RED, an Alexa 65 or a Sony a7S, you can’t tell because of all the wires and accessories. That’s not just an opportunity, but almost a responsibility to clean this mess up, to work with the camera manufacturers to get to a system where we retain modularity and options but also have something of a standard.

I desperately want to try and unify these things into an interoperable, simple to use, lower risk system. It should have fewer points that break, and it should also be stylish. It pains me to think our customers are in the business of creating beautiful images. They create art. They all have a deep sense of artistic awareness and we give them these ugly rectangular boxes that Velcro to their cameras.

I don’t think we have paid enough attention to design, to elegance, to the fundament of making the tool something that disappears so you can just get the job done. You don’t want to focus on the tool. But the tool should still be something that gives you joy because it’s actually elegant and it’s borderline pretty.

So, I’m officially a fan boy. Everybody knows this about me. If I look at your average Dell keyboard, I can’t get excited. But the moment I open my MacBook, I honestly enjoy the interaction with a Mac. It’s something that’s carefully crafted. It’s beautifully designed. Yes, I’m more productive on it than I am on a PC, but it’s not only about that. It’s because I’m actually interacting with a thing of beauty.

And so, if we are providing tools for cinematographers who are in the business of creating beautiful things, then obviously they’re going to appreciate the tool if it is beautiful or elegant, as opposed to some clunky box of little black rectangles.

So, that’s the big picture for Creative Solutions. We want to build an ecosystem of accessories that surrounds the camera, that extends its capabilities, but in a way that’s very carefully thought out and crafted to be very elegant, with fewer connectors and cables and fewer failure points because of poor design.

That is a multidisciplinary approach. It’s mechanical, electronic and software. And it’s RF. And so if you look at that context, then the Amimon acquisition has always been dead obvious. But, enough of sitting here in a conference room.. Let’s meet some of the key people here at Amimon and tour the facility.

First of, Amimon is ISO 9000 certified. This is not a trivial accomplishment. ISO 9000 holds a company accountable. It that means that all of the manufacturing and engineering has a well-documented process. It makes it repeatable and trusted. Amimon has a level of maturity and manufacturing technical ability that’s higher than most.

I’d like to introduce you to the Amimon team, show the sophistication of their technology and what it takes to achieve this level of performance. I’d like to explain how difficult it is, how special it is, why it matters and why this is the right choice at this point in time.

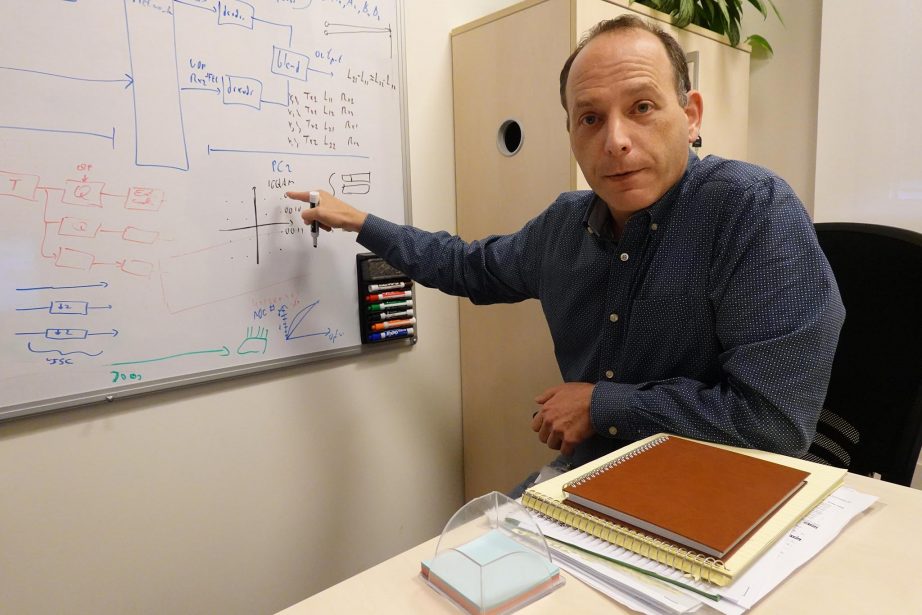

Dr. Zvi Reznic

JON FAUER: How did it all begin with you and Amimon?

ZVI REZNIC: It’s a funny story. I received my Masters Degree at Cornell University and PhD at Tel Aviv University. Originally, there were three of us who founded Amimon. Professor Meir Feder was my PhD advisor and Noam Geri was a friend of mine who lived in the U.S. The three of us together were thinking about a new start-up. It was in 2003. We began by thinking that adding MIMO (Multiple Input, Multiple Output.) to Wi-Fi was a good idea. We got an offer of funding. But then we decided that Wi-Fi was a game for big guys like Broadcom and Intel.

MIMO refers to having multiple antennas on both the transmitter and the receiver. Each transmit antenna is transmitting a different signal, but they all transmit simultaneously and in the same frequency. Hence the receiver receives a mixture of all the transmissions. Nevertheless, since the receiver has also multiple antennas, it is able to separate the signal to its individual components. It is like solving multiple equations with multiple unknowns.

Basically, MIMO increases the channel capacity by a factor that equals the number of transmitter antennas. It’s a very powerful tool. It was invented at Bell Labs in the mid ’90s. So we were thinking about bringing MIMO to Wi-Fi, but then we dropped that idea.

We thought that our expertise was in bandwidth utilization, extracting the most out of every hertz. We asked, “Where is the need for that? Where is the bandwidth shortage?” I remember, I had a whiteboard. We sat three across in our tiny, one-room office in Herzliya. I cleaned the whiteboard. It was now blank. And I wrote, with a big question mark, “Who needs bandwidth?” We thought about it for a while. And then we got a telephone call saying that a guy from Toshiba was visiting Israel and wanted to talk with us. It was very difficult to understand what he wanted. Back at the office, we realized that maybe he meant wireless DVI.

We started reading about DVI and HDMI and realized that the work I was doing on my PhD thesis might be relevant. My research was about communications with distortion on channels of unknown signal-to-noise ratio. That’s exactly what you have in wireless video. And the goal is to minimize the distortion. So that was the beginning.

How did you come up with the name Amimon?

When we started the company, as I mentioned, we thought of developing MIMO for WiFi, and we called ourselves Hydra Wireless. Later, we changed our plan to Wireless DVI/HDMI. When we found investors for the new venture, the investors wanted us to start a new company, so we had to find a new name. We couldn’t think of a name, until one evening I was on my way to a meeting with the investors and the other founders. The lawyer called and said that we must decide on a name, otherwise it will delay the deal. Since I was driving, I called my wife and asked her to search the Internet for something connected to Hydra in Greek Mythology. She looked up Hydra in Wikipedia and quickly scanned for a nice name. She found AMYMONE (the spring of Amymone was Hydra’s lair). When I arrived, I met the other founders and suggested this name. They didn’t like it, but said they could accept it if we changed the name to AMIMON, which is a simpler spelling and also has MIMO in the middle. The investors then entered the room. We told them the name of our company was “Amimon.” They didn’t like it either, but we closed the deal anyway.

Sorry for the long story, but that is how it was.

What makes your technology special?

Basically, the challenge is that you want to send pixels wirelessly over noisy channels. This goes back to Claude Shannon’s original paper from 1948 where he invented and introduced the field of “Information Theory.” Shannon suggested that the way to solve this is to first compress the signal, and generate bits at the rate of R bits per second. You take these bits and transmit them reliably over the channel. And in order to transmit them reliably, you compress your video to a bit rate of R bits per second, such that R is below the channel capacity. Then, you will be able to transmit these bits to the other side reliably. And then, at the receiving end, you do the opposite—you take the bits and you decompress them.

However, in order for this to work, the bit rate R must be smaller than the channel capacity C. However, in wireless channels, the capacity C changes rapidly.

So if you want to have a robust system, you want to tune the bit rate R of your compression to be below the worst case of the channel, with even some extra margin, so that, even in the worst case, your communication link will not break. Another way of doing that is to say, “Okay. I’ll take the risk and I’ll retransmit from time-to-time. I’ll compress it to a slightly higher rate. Most of the time it will be okay. But occasionally, it will not be okay. And when it will not be okay, the packet will be lost. But then I will retransmit the packet.” The problem with retransmission is that it adds delay to the system, which is latency.

Our solution is that we’re able to basically vary the amount of information that we receive to match the instantaneous capacity of the channel.

And nobody else thought of this before?

The idea of joint source channel coding was studied in the universities and academia before. But we invented the way to connect video compression and joint source channel coding this specific way. On top of that, we take the most significant part of the video, what visually matters the most, which is usually the low frequencies and we protect them with high compression, low bit rate, so that they will always pass through.

We give weaker protection to the less significant video information. Actually, most of the information is less important. So there is a little information that is important, and tons of information that is less important. But you want to have them all, because that’s where the quality comes from. As for audio, we send that at very low bit rates to make sure it is very robust.

But your video is great because we see details and edges nicely for focus. You can even see the texture of someone’s eyelashes.

And that’s the good thing, that’s the idea. We do send the high frequencies because we want to have that information. I’m not saying it’s not important. But if something goes wrong, for example, a channel drops, I want to make sure that only the high frequency part is being affected, and not the low. It is also proportional and might only be the duration of a frame, or much less than a frame.

Probably the person who benefits the most from this low latency and high quality is the focus puller who is focusing off the monitor constantly. And it’s usually the pupil of the actor’s eye.

If you would use a traditional system, that information would not even be transmitted. We’re sending much more information, including the very high frequencies. It’s just that, from time-to-time, if the channel is degraded for a small duration of time, then that could be affected briefly.

Zvi, since you’re the algorithm architect, perhaps a future focus friendly model will take the actors’ eyes into account.

This calls for a “region of interest” algorithm, in which the system automatically identifies important regions within the frame, and allocates more bandwidth for that region. We can look into what it takes to apply the region of interest to actors’ eyes in future chips.

Do video signals from sensors start out life as analog signals and then go through an analog-to-digital conversion process?

That’s the thing. Traditional digital video compression involves the process of quantization. But that’s evil. For example, look at a gradient—a blue sky is a good example. If you take a blue sky and put a strong JPEG compression on it, it’s going to look bad, with bands and blockiness. Basically, all of the different values in that area are now described as the same value. That’s quantization and those errors are visually very painful. Instead, let’s send some of this reliably with error correction, digitally. Send a little bit more with less error correction, but also digital. And then send the rest analog. You have to compare it to the alternative. Because it goes back to Shannon. If you have a limited capacity, then eventually you will suffer from some distortion. And the trick is to minimize that distortion.

You mentioned analog. In the days where film cameras had video taps, video assist was mostly analog transmission via standard TV channels. How do you get around the transmission distance problem in the analog portion of your process?

We are using five receive antennas, and either two or four transmit antennas. Having more

receiver antennas than transmitter antennas increases the range and the robustness.

You asked before about a purely analog system. Video has an inherent redundancy. So purely analog is not trying to remove that redundancy. Color information from one pixel next to the other is usually similar. There are similarities between neighboring pictures. In purely analog, you don’t take advantage of that. You treat every pixel as very new information.

You asked before about a purely analog system. Video has an inherent redundancy. So purely analog is not trying to remove that redundancy. Color information from one pixel next to the other is usually similar. There are similarities between neighboring pictures. In purely analog, you don’t take advantage of that. You treat every pixel as very new information.

But when you go to digital, things like DCT take advantage of this and remove the redundancy, reduce your bandwidth. This was done in compression with JPEG and MPEG and so on. But then other problems were encountered, because analog was completely robust and digital is not robust. So we found a way to get the best out of the two worlds. We have the robustness of analog with the bandwidth efficiency of digital. This would be the equivalent of a 4 Million QAM modulation (quadrature amplitude modulation).

Amimon Technology

JON: Why is Amimon alone in building video modems for cine?

JON: Why is Amimon alone in building video modems for cine?

NICOL VERHEEM: It is an interesting coincidence. I almost want to call it a series of unfortunate events. Over 10 years or so, Amimon raised or spent something like $50 million dollars on R&D to develop their video modem to where it is today. They raised money on the premise that they’d replace every HDMI cable on earth. There were Venture Capitalists, VCs, who thought this company would be worth billions of dollars.

That’s a lot of HDMI cables to replace.

They put in tens of millions of dollars because they thought they’d make billions of dollars in return. Unfortunately, consumers basically said, “We’re going to replace the HDMI cable, you’re right. But we’re going to replace it with Wi-Fi, not with your propriety link. Because we want Packetized IP. We want Smart TVs that have the Netflix app running inside. The Amimon technology was not that applicable, so that’s the first unfortunate event.

The other relates to their starting the company in the heyday of fabulous semiconductor companies in San Jose. Everybody was making chips. And those chips ended up in a massive variety of devices. But then, over the last decade or so, that whole industry changed. And now there are essentially 5 or 6 platforms that you want your chips to be designed in and they’re mostly cell phones. The cost to design a chip has become more expensive. There are not as many people around with the appetite to fund chip companies. Apple makes their own chips. Samsung make their own chips. Google makes their own chips. Facebook now makes their own chips.

So the notion of another fabulous semiconductor chip company is a relic of the past. Luckily for Amimon, they did not fail because they pivoted away from being only a chip company and reinvented themselves as a module and product company. That kept them going. But it’s a much more modest revenue model. Fortunately, we’re now in a position where we’re benefitting from the heyday of VCs investing in fabulous semiconductor companies that resulted in this amazing technology.

It’s something that is not likely to repeat again. So that’s why there are not a dozen other people building video modems. It’s actually a niche market. Luckily for all of us, some VCs miscalculated and thought that it was going to be a massive opportunity and invested in a lot of this IP.

Then how are you investing in the next generation chips?

Once you have the basic intellectual property framework, including the patents, then the incremental cost is less. You still should keep a reasonably modest approach rather than trying to build to the newest 7 nanometer standard.

Amimon makes the chips and circuits in Teradek and Paralinx wireless systems as well as ARRI and Transvideo. Do these different receivers and transmitters all work with each other?

Not all, and here’s a little bit background. The wireless link that we use is encrypted so that other people cannot eavesdrop. This is very important to a lot of our customers. There is a process that’s called a “key exchange” between the transmitter and the receiver. They become trusted parties to each other. You can pair more than one receiver to the transmitter, but you have to physically set the links up beforehand.

There is a private and a public key, just like the encryption that you use for your online banking. The keys used by the different companies are all unique to each, like different banks. We made a choice, after acquiring Paralinx, to share keys with them. So Teradek and Paralinx units work with each other. But ARRI, or any of the other manufacturers, all have their own unique keys. The systems are not interoperable. They’re exclusive by design.

Of course, that’s not what our industry wants. It is my hope that we can all come together and create a standard in which the systems are interoperable, but still protected as required.

It’s awkward that the different systems do not work together.

By design, each link is protected with encryption because we don’t want unintended parties to eavesdrop. But you do want interoperability, which we as an industry failed to get, because we are too busy competing with each other. Now it really makes sense to reach out and try and establish a common standard. Clearly, it needs to be something for which people opt in and there needs to be some responsibility. We don’t want a partner to give these keys out and jeopardize the whole systems integrity.

Some of the Amimon counterfeit products out there are using an older generation of the Amimon technology. They all use the same key across multiple manufacturers and across multiple devices. They just hard coded. So you set the transmitter channel and then dial the receiver until it connects, as opposed to negotiating a secure link between units. The transmitter then is just literally broadcasting. The problem is, if someone nefarious gets to within 10,000 feet of a new Marvel Movie that is using one of these transmitters. They just dial back and forth between the 11 channels until they find your signal. They now have an uncompressed video feed off Camera “A” in the apartment next door to the studio.

But can you reassure existing customers of legitimate products that they will be supported going forward?

Let’s take ARRI as an example. ARRI is a brand that does not do stuff halfway. ARRI’s wireless video products based on this technology were all developed in conjunction with Amimon, using the approved Amimon hardware and Amimon provided software, and they got it certified according to all the proper regulations in all the markets in the world. So that is what I would call a legitimate product.

- Teradek Bolt 3000 TX Transmitter on Teradek Bolt on VENICE Teradek Bolt on RED DSMC2 left and RX Receiver on right

- Teradek Bolt on VENICE

- Teradek Bolt on RED DSMC2

Any manufacturer that has only legitimate products will likely continue to receive our support. But there are products that are based on recycled Amimon hardware, with illegal copies of old Amimon software, which has never been certified to be used outside of a lab. It’s really just test software, that hasn’t been properly tested for the proper FCC, DFS, or FAA regulations.

We know through some of the testing that these products are illegal. They’re operating with too much power and on channels for which they were not certified. It’s the Wild West. There are counterfeit products that take some consumer products of Amimon, but then repurpose them, change the electronics to boost the output power in a very illegal way, use them on channels for which they were never certified or ignore all the regulations about channel selection, but then, the products might have pretty good performance.

Think of it this way. If we had a street race from Point A to Point B across town, you can take a little Nissan Sentra and I can have the best-designed Lamborghini. If I then stop at each stop sign and red traffic light, but you don’t, then quite likely you’ll win in your Nissan Sentra.

Sometimes people do product shootouts, and they find that these other products work better than the Teradek product. Well, that’s because they don’t follow the rules. It is important to understand why those rules are there in the first place. Some of these rules are about health and safety. The output power is governed so that we don’t all fry our brains. Some of these other products are actually interfering with aircraft or weather radar systems that are used by air traffic control to figure out what the conditions are.

These are serious rules. They’re not silly bureaucracy. Every government on Earth tries to manage the wireless frequency, the RF radio spectrum, to allow multiple conflicting applications to co-exist peacefully.

You’ve got broadcasters trying to send television signals. You’re got first responders and police trying to communicate with each other. You’ve got cellular providers trying to provide bandwidth. You’ve got weather systems, airplanes, microwaves, X-Ray machines. All of these things are using RF. And the government allocates it in buckets of bandwidth, and you really have to comply.

Coming back to your question, people with legitimate products based on Amimon technology that were developed in collaboration with Amimon will continue to be supported. The other people, we’ll address one-by-one.

I had no idea there were two different worlds of “legal” and “illegal” wireless video. Are you at liberty to say who the supported, good guys are?

I’m still learning. I know, ARRI and Transvideo are “legal.” It’s hard to separate it in two camps. Over time, we’ll clean this up. And we’ll implement new license agreements so any legitimate party will not have an issue.

Looking at it from the outside, it seems it is in Teradek’s and Vitec’s interest to keep supporting the legitimate companies and not try to drive them away.

Definitely. May I try to explain it a different way? If I were to justify our acquisition to a bank and not to somebody from the industry, I would only talk about a lot of the opportunities for us to create new technology which we cannot do alone, in house.

We cannot do it by ourselves because we don’t have the underlying technology, the R&D resources and the skill sets.

We acquired Amimon because we now gain 65 brilliant R&D engineers. We only have 20 people in R&D in Irvine at Teradek. It’s still a small company.

Amimon is a really high-tech facility, with incredible existing intellectual property that we can build upon. But it’s impossible for us to do what Amimon does from scratch. We’re not a chip company. We can’t build our own video modem. For us to build one would take 65 people and another 10 years. And then we’d end up with something that Amimon already has.

So, we acquired Amimon to partner with their R&D teams because we see an opportunity: If we focus those resources on the right market, the cinema market. We think that, together, we can add value and make a substantial difference. We can make a meaningful impact on the industry if we navigate the right way.

I bet you wanted to do this for quite a long time.

Yes. I’ve been making a case for Vitec to acquire Amimon since 2014. I’ve probably written 200,000 words to that effect over my tenure there. I’ve been trying to convince Amimon to sell to Vitec for just about just as long. It just took a really long time for each of them to realize it’s an excellent opportunity for all. It has been, by far, the most difficult acquisition I’ve ever done.

And it’s your biggest as well.

Ikigai

Nicol Verheem and I were walking along a windy Herliya Beach. Nicol asked me:

Have I ever spoken to you about Ikigai? As you know, I love analogies.

This was a rhetorical question. Nicol did not wait for a reply nor did he need prodding. He was in a contemplative mood and this was to be a philospher’s walk. After several days of deep diving into wavelengths, frequencies, 1024 QAM, WIMO, MIMO, Fourier, Shannon and Einstein, Nicol needed to exercise his creative side as well as our legs. And so the wrap-up began with Ikigai.

Nicol continued:

Ikigai means, “A reason for being.” It is a Japanese philosophy about the meaning of life and how to achieve fulfillment. And it proposes that life becomes meaningful if we actually do something that is worthwhile and impactful to the rest of the world.

We can’t ignore the fact that we spend much of our life at work. If you put in 10-hour or 12-hour days like we do, and you need some time to get ready for it, to unwind from it, then hopefully you get seven or eight hours of sleep at night. Your life outside of work is actually very small. If you have happiness at work, chances are you are a happy and fulfilled person.

“Dr. Reznic and the team at Amimon realized that we can get much closer to Shannon’s theoretical limits by treating the video and the channel as one, as opposed to treating them as two separate things. They’re not violating Shannon’s Law. They’re embracing it, pushing it right up to the limit.”

This Japanese concept of Ikigai addresses how you might achieve that. It explains that there are four things you should value in your reason for being. You should do what you love, do something that the world needs, that you can be paid for, and that you’re good at. Those are the four elements. When they all intersect, you have achieved Ikigai.

But if you only have two of these, say, what you love and what the world needs, but you can’t get paid for it, that’s a mission. But it’s not Ikigai. If you do what the world needs, and you can get paid for it, but you don’t love it, that’s a vocation. What you’re good at and can be paid for is a profession. What you love and are good at it is a passion. All four have to intersect to get Ikigai.

I feel that with Teradek and Creative Solutions, I have found Ikigai. I love what I do. Love the people I do it with. And so on.

Let’s go back to talking about Amimon. When I started Teradek, it was bootstrapped from my second home mortgage. And then there was a turning point in 2010 where we pivoted and started embracing the market of creatives.

That’s where I started having more Ikigai, because I loved creating tools for creatives. I identified with it on some level. I’ve never been a cinematographer like you and your colleagues. But at one point I was a very passionate landscape photographer. As you know, I’m absolutely obsessed with this stuff. I still have a respectable collection of 4×5 lenses for my Arca Swiss Field Camera. That’s still my favorite tool even though I never get enough time with it anymore.

When we actually started building tools that creative people used in the process of making a movie, a TV show or a commercial, I felt much more fulfilled than when I was just making a security camera at GE or working as a rocket scientist. Those jobs were technically challenging but they were not as rewarding. They didn’t speak to my artistic side. Even though I’m still not an artist I now enjoy working with artists. I absolutely love watching a behind the scenes video and get a thrill whenever one of our products shows up.

It gives me a sense of pride. From that pivot, everything has led up to the acquisition of Amimon. As you know, I fell in love with the cinema industry and building tools for it. But I was vexed that our contribution was perhaps a bit superficial. We took something and we subtly shaped it, molded it a bit, badged it, and then sold it to someone working in cinema. But the underlying part wasn’t ours in the sense that we deserved most of the credit for it. More importantly, it wasn’t ours to completely direct.

Some people might be tempted to think we acquired Amimon simply for supply chain reasons or because we wanted to control all the access to this technology. Or maybe in astute business model mode, some people might say we wanted to secure access to this technology because we, like anyone else, we were at risk of losing it at some point if the company failed or we were acquired by someone else outside our industry.

Those are not the reasons. We acquired Amimon because we want to influence and direct this technology, so that we can apply it to what we’re really passionate about, which is the cinema industry.

If you think back, Dr. Reznic, you and I sat in a room and he explained the technology. We discussed three scientific/mathematical theorems and how you can prove them from within the rules of math itself. We talked about the Shannon Information Theory. Everybody who studied electronic engineering or anything in communication will be familiar with Claude Shannon and his paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” also referred to as Shannon’s Limit. It basically says, here is a physical channel, and the physical channel has some physical characteristics that give you an absolute maximum amount of information that can be sent through that channel. You will never be able to exceed it. Just like entropy or relativity, it was derived from fundamental math. Like Entropy, and unlike Einstein’s Relativity, people don’t question this. They just accept Shannon as gospel. Nobody is trying to prove Shannon wrong. Since 1948, everybody agreed that his math was correct.

Dr. Reznic and the team at Amimon realized that we can get much closer to Shannon’s theoretical limits by treating the video and the channel as one, as opposed to treating them as two separate things. They’re not violating Shannon’s Law. They’re embracing it, pushing it right up to the limit.

The Amimon concept was something fantastic, incredibly smart, but it was misdirected in the markets in which it was applied. It was this fundamentally beautiful thing but all they wanted it to do was to replace a damn HDMI cable. They took something that was so special and applied it to something that was so mundane. Enter Teradek in 2012. We took that concept and applied it to the world of cinema. In the process, I nearly went bankrupt , but ultimately, we were rather successful. Amimon survived because of it. Everyone in the industry benefitted.

I found myself in a very lucky position. I became sort of a translator between the Amimon team, with their incredible talent and intellectual property, and the industry with its requests. I was the translator of things that Amimon could implement, and then translating that into something people could apply. That was my role.

Sometimes we get a pushback from the industry because we’re considered a big dumb company with a good market share. I can see how people might feel that way. But, the reality is, it’s a good market share in a very small market. We still are a very small company. You visited my office last year. I actually still have the original, cheap open office furniture I bought open box from Plummer’s. That’s a furniture store in California, like an Ikea. I remember starting Teradek from my second mortgage, and going to the local furniture store. I picked up a bunch of chairs and a glass table. They were floor models, flimsy stuff. And that’s the office furniture I still have today together with my 2011 iMac! We are absolutely still a scrappy startup. The fact that we achieved a decent market presence and market share in a little niche market doesn’t change who we really are.

You might ask, “But aren’t you part of a big corporation which is Vitec?” Yes we are but we continue to fight long and hard to maintain our identity. That’s why we are part of Creative Solutions, a separate division of Vitec. We focus specifically on exciting, younger brands. It’s been about 5 years now since Vitec acquired Teradek. The journey continued with SmallHD, Paralinx, Wooden Camera, Off Hollywood, Rycote, RT Motion and now Amimon joining Creative Solutions. There are 350 people working in 10 locations.

There is another analogy that comes to mind. We were in Tel Aviv a few weeks ago. It was incredibly stressful. The closer you get to the finish of an acquisition, the more stressful it usually becomes. We finished the work in the nick of time. We were standing in front of our hotel, Herods in Herzlyia: Marius, our COO and a team from Amimon. Not to sound too Biblical, but the heavens opened up. It rained two inches solid. We had just come from California where the forest fires were burning and is was smoky, dry, and miserable. So we loved the rain. Here we were, standing in Israel, in a place that I would expect seeing so much rain. I said, “That has to be a good omen: two Californians standing here in Israel in two inches of rain.” The locals, of course, did not like the rain.

There is another analogy that comes to mind. We were in Tel Aviv a few weeks ago. It was incredibly stressful. The closer you get to the finish of an acquisition, the more stressful it usually becomes. We finished the work in the nick of time. We were standing in front of our hotel, Herods in Herzlyia: Marius, our COO and a team from Amimon. Not to sound too Biblical, but the heavens opened up. It rained two inches solid. We had just come from California where the forest fires were burning and is was smoky, dry, and miserable. So we loved the rain. Here we were, standing in Israel, in a place that I would expect seeing so much rain. I said, “That has to be a good omen: two Californians standing here in Israel in two inches of rain.” The locals, of course, did not like the rain.

- Herods Hotel in Herzliya. Stay there if you go to visit Amimon.

- Detail of Norman Teeling’s O’Connell Street in Dublin.

I replied, “You know, I’m at that point in life where I’m just starting to perceive things a little bit differently and starting to appreciate smaller things. Like rain in dry places.”

It’s similar to how I learned to appreciate art. These days whenever we go on a trip, I try to find an affordable art gallery and buy an original painting by a local artist. Hopefully, it captures the landscape or the city we are visiting. Originally, I just wanted to take my own photos. To me, art was landscape photography. But later on, I learned to appreciate painting. I enjoy paintings where the artist uses a palette knife or very rough brush strokes. I appreciate impressionism and pointillism. Above all, I like texture.

And then I thought, “Maybe this is how life is, how your perception of art develops, or even how your senses develop.” Think of it: when babies are born, one of the first things they notice is color. It might be a giant red or green blob above the crib and a blue thing that spins. Then they develop a sense of space and dimensions and shapes. But texture come much later.

Maybe that’s how it was in trying to build Teradek and Creative Solutions. Initially, it was just, “Build a company. Try to earn a living.” That was the baby’s red, blue, and green. And then we grew. We added more companies, built more pieces that attached to cameras. But now I’m at a point where it’s not good enough for me to just run a bunch of brands. I want to have real excellence in design, and smooth integration, and build things that can stand the test of time , hopefully be around a hundred years from now.

That’s texture. It’s one of the last things for which you develop appreciation. But in a way, it’s the most rewarding. The paintings that I love the most, all have texture. If you look at a painting up close, you can see the brush strokes, some colors and textures. Very often, you do not see the actual objects or the purpose of the picture. But step back, and it becomes clear. It’s a wooden cart or someone standing on a hillside or a landscape at sunset.

A good example is Norman Teeling’s O’Connell Street in Dublin. Go up close and you can’t make head or tail of it. You see yellow, blue and red splotches, and a patch of purple. When you step back, all these colors start to blend. You can’t find that purple again. But you see the people, and the cars.

Above: Norman Teeling. O’Connell Street in Dublin. Oil on canvas. 32 x 32 in. Norman Teeling is a leading Irish Impressionist. He graduated from the National College of Art and Design, Dublin. He also worked in animation and on features as a background artist. normanteeling.com

That’s analogous to my journey. Merely looking at Amimon as a supplier, or Teradek as a brand, you’re just seeing the colors in the picture. You might be seeing the objects of the scene. But you’re not paying attention to the texture. Only once we appreciate texture do we truly understand the scope of what we’re trying to achieve.

Amimon Tour

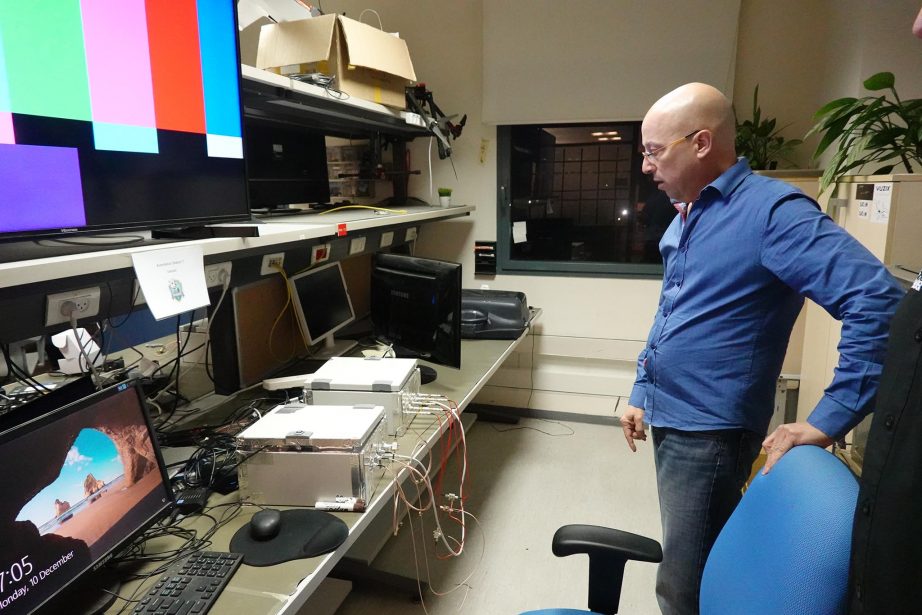

- Testing 4K system, comparing latency and quality.

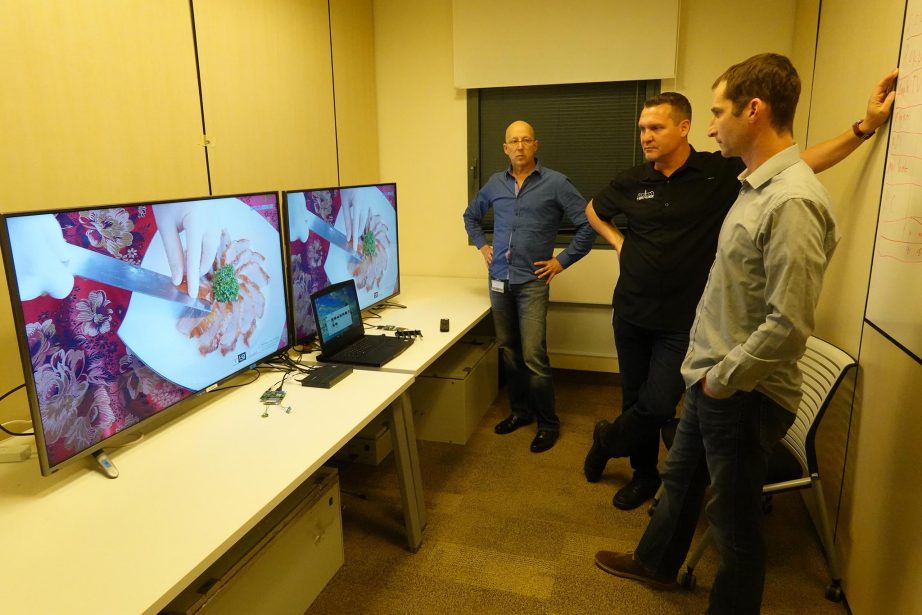

- Testing wireless video in real time on real cameras, gimbals and rigs.

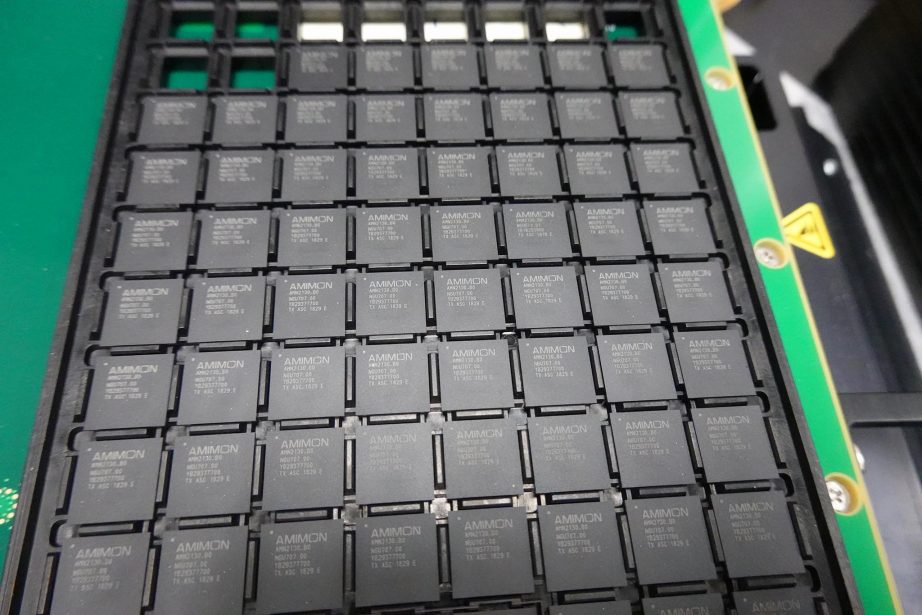

- Testing chips.

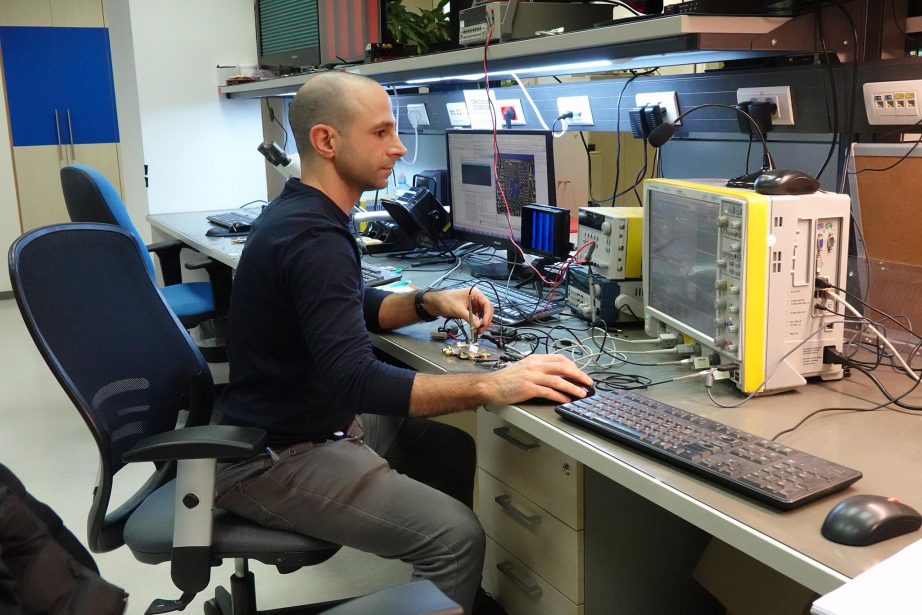

- Designing circuitry.

Reprinted from Film and Digital Times February 2019 Edition #92