“Wolf Hall” is the series on BBC and PBS Masterpiece Theatre about Thomas Cromwell, played by Mark Rylance—a blacksmith’s son who rose to power as chief minister to King Henry VIII. Gavin Finney, BSC was the cinematographer.

JON FAUER: This is an interesting story. “Wolf Hall” was shot almost entirely handheld with Alexa and Summilux-C primes wide open at T1.4, and the night interiors were lit with candles?

GAVIN FINNEY: Yes. That was a practical solution and clearly an artistic one as well. It stemmed from the wish of the Director, Peter Kosminsky, to shoot the whole drama handheld. He wanted to shoot it in a contemporary documentary style. Handheld not in a waving-the-camera way, but as a proper documentary cameraman would hold it, which is as steady as you can, with a pleasing looseness and fluidity. He also wanted to give the actors freedom of movement within real locations.

Often, that meant coming into a room wide over the shoulder of Mark Rylance and then moving around to see his face, to see his reaction. We would never see anything that Cromwell’s character doesn’t see. That is why we don’t meet King Henry until the end of episode one: because Cromwell doesn’t meet him. Also, when you’re in a grade-one listed building, where you cannot touch the fabric because it is so precious, and you’re shooting on a wide angle lens handheld at night, where do you put film lights? I’m not a fan of lights simulating moonlight by coming through windows to light up things. That’s not how it was. And sometimes we’d be shooting during the day for nighttime, blacked out. It was in most cases real candlelight.

Your camera work was so beautiful, I didn’t realize it was handheld.

It’s 98.5% handheld. There’s one crane shot and there are a couple of instances where we used a long lens with a 45-250 zoom, which is just too big to hold. For the jousting tournament in episode six, and one or two other times, we were on a ladder-pod to get up high. The camera was resting on a Halo Rig, which is like a miniature inner tube donut that you can rock. It gives the camera a slightly loose and handheld feel. We didn’t take the tripod out of the van until week five.

It was not shaky-cam. It was good handheld.

That’s the thing: all the static shots are also handheld. If you look at it you’ll see there is a slight amount of movement but it’s just my natural body movement. Peter’s instruction was to have it look handheld when we’re walking as well as when we’re still—but to try to keep it as still as I could. It has an immediacy, a looseness, so the actors never felt pinned down by a track-run dolly. If they wanted to change where they were in the room, they could.

You had the freedom to move with the actors and the lighting allowed you to do that as well?

We had real candles in the rooms at night. During the day most of the light came through the windows. Usually we had 18Ks on cranes coming through big windows. What surprised me is that Tudor buildings have a lot of glass: big, almost floor-to-ceiling windows, and so that was how we lit. You structure the scene so that people are near windows or near candles when you want to see them.

Did this documentary style come from starting your career in documentaries?

Certainly, I did documentaries both at Film School and when I left. It was a combination of drama and documentaries. Unfortunately, people tend to pigeon-hole you, so if you do dramas they don’t see you as a documentary cameraman and vice versa, but when I was starting I did quite a few docs and I love them. You learn a huge amount just doing documentaries. You actually learn how good things look when you don’t mess them up with lighting.

In the candlelit scenes, were they double wick or single wick normal candles?

Double wick candles are a problem in that they burn down faster, so you have to replace them more often for continuity. They produce more smoke. The locations we shot in required a huge amount of negotiation even to let us light any candles. But they prohibited double wick, because these are very precious interiors, 500-600 year old buildings, and they didn’t want the heat or the smoke to damage the hanging tapestries and woodwork. So we had to use single wick beeswax candles or beeswax blend church candles, which have reasonably good sized single wicks.

In episode 2, Cromwell is talking to his sister-in-law and at the end of the scene he says, “I shouldn’t have said that…”

Actually, it’s one of my favorite scenes in the film. Because we’d done a lot of testing, we knew that it would work. When I read the script, it said, “Johane walks around the room putting out all the candles.” And I thought there goes my lighting source, but it did work.

You can feel the darkness enveloping Cromwell. We lit to T1.4 at 1600 ASA. The camera sees significantly more than the human eye sees.

The learning curve of working with candles is putting them where they look correct for the room. It’s also putting them where they look correct for the actors, because they are your lighting source, and

it requires structuring scenes so the actors are near the candles. In this scene, it’s actually quite useful as Johane goes around turning out the candles because she’s always near a candle until the final one. She’s silhouetted by the candle light on the wall.

At the end of the shot there’s just one candle and the fireplace light on Cromwell. That’s it. There’s nothing else. There’s no other artificial light (apart from a KinoFlo tube on a crane outside the window). There were times in a couple of locations where I had to use very small sources, like Kino Flo tubes or Dedos. There’s a scene in episode one where Cromwell is putting his children to bed and that was lit by candle and fire light, but his face is just too close to a bed hanging. There was a rule that we couldn’t have any flame closer than 90 centimeters to any fabric, wall or furniture. There were a couple of occasions where I had to use artificial light, but most of the scenes were lit by what you can see.

Did you use any LEDs, like artificial candle LED lights?

No, the only LED fixtures we had, and we did use occasionally, were the Kino Flo Celeb 200 and 400. We used them dimmed between 1% and 3%, with a 1/4 CTS and often with a Lee 251 Diffusion.

You rated the entire series at 1600 ISO?

Nighttime was all 1600. My Gaffer, Andy Long, made up some candle trays out of metal with reflective sides and backs, which could hold 20 or 30 church candles. These could go on a stand and I could use those to boost the light, as fill light or to put more modeling in. So I had extra lighting, but it was still candlelight.

If we wanted less light we blew out some candles, so it was what you might call a dimmable candle system.

Sounds like the next new product at Mole or Kino Flo. Were they bi-color? Bi-color candles could be big.

Yes, very bright, bi-color eco candles!

The camera was ALEXA?

ARRI ALEXA, shooting ProRes 444 Log C and no filtration at night.

Let’s talk about the lenses.

They were Leica Summilux-C primes. In testing, the Director, Peter, hadn’t shot digital before. Up to now he’s always shot film.

When I went in for the interview, I said, “Let’s just test everything out there. I don’t own any cameras, so let’s use every available camera and every available lens. Let’s look at them all in daylight, in candlelight, look at the people in rooms, and then use the system that works best for this production. So we tested ALEXA, AMIRA (which was in prototype then), RED Epic Dragon, Canon C300, C500, Sony F55 and then Cooke S4, Ultra Primes, Master Primes, Leicas, Canon K35s, older glass, the whole gamut. What we liked about the Leicas was how they were very true and had incredible solidity wide open. Other lenses filled in the blacks a lot when they were at T1.4, whereas the Leicas had great contrast and very beautiful colors at T1.4 and zero chromatic aberration as far as I could see. I really didn’t want to have chromatic aberration: it just looks like a modern artifact, that magenta-green hue on candles. The Leicas had none at all. You won’t see any chromatic aberration, just a lovely, very subtle bloom around the candles. We tested filters as well, but all the filters, even at the weaker strengths, were too much. At such low light levels, they just covered everything in a kind of haze.

Do you think the bloom around the candles was from the lens or from the camera?

Different lenses had different effects, so I think everything works as a system. It’s certainly largely a product of the lenses, but I’m sure a part is also the sensor. The other reason for not filtering was we didn’t want to have to deal with double reflections.

When you’re walking into a room with 220 candles, you really don’t want to be dealing with angling filters and trying to get rid of all those reflections. We found that different systems created varying degrees of bounce off the sensor: the candlelight would hit sensor, reflect off the rear element, and then go back to the sensor again. Certain camera-lens combinations were worse than others.

I guess the Leicas are more telecentric, so that may have helped.

Absolutely. I think Master Primes probably had the least kick-back and the Leica’s had very little. I usually do tests with people, fruits and vegetables. I’ll get a bowl of fruit with oranges, lemons, bananas, eggplants, and limes, and then I’ll put a man and a woman in the scene as well. I don’t really do tests with lens charts. I test what I’m going to shoot. And then obviously for candlelight we had lots of candles. The Leica’s just seemed to nail it. They had a beautiful, solid rendering of people and things. It is hard to put it in a more technical way. They just looked right. It’s funny though, the Master Primes actually had a modern look. When you look at the image, to my eye, and this is an aesthetic that’s subjective, they just looked modern. Whereas the Leicas seemed to have just a little bit more of a period look, for want of a better word.

The lady, Cromwell’s wife, sewing by the window was like a Vermeer.

Yes, thank you. That was just the light from outside, and natural bounce from her costume and surroundings.

In the office scene where there’s a globe, it looks like Vermeer’s “Geographer.”

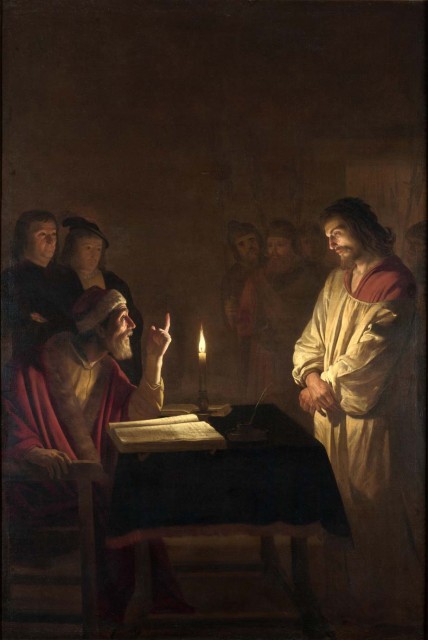

We studied Vermeer, and Caravaggio, and Rembrandt, because they were witnesses to what the world looked like at that time. In that era, interior lighting was with candles, and the paintings of that period and show how people looked in candlelight, and how rooms looked in that light. We took a great deal of effort looking at references. I was looking through my folders trying to find particular artists apart from the obvious ones like Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Another artist we used as a reference was Gerit van Honthorst, who lit faces very realistically with candles in the scene. A single candle is quite a point source. Often the candles were low, which is not that attractive on a face, but it’s exactly what the world looked like. Sometimes the neck and the underneath of the jaw is very white and then it fades off. It’s not how you would light now.

Christ before the High Priest. By Gerard van Honthorst .circa 1617 Oil on canvas. 272 x 183 cm (107.1 x 72 in). National Gallery, London

Usually candles are props. Then you bring in film lights to make everything look gorgeous and you blend it in. Whereas lighting just with candles takes you to a different aesthetic.

When you were doing the night interiors with candlelight, was it a challenge to use small point sources as opposed to large and softer units with diffusion?

Sometimes the firelight was a bit aggressive. When it was out of shot, but still a source, we would put a diffusion frame in front of the fireplace so we still had the flicker, but it was slightly softer. In fact, there was an exhibition at London’s National Gallery with a textbook on painting by Leonardo Da Vinci. It was open on the page of how to paint portraits at night. And he recommended putting a very fine piece of parchment between the candle and the subject to soften the light. So I thought, well, if Leonardo’s doing it, I can do it too.

When you were lighting your actors with candles, how did you position them to be pleasing to the modern eye as opposed to multiple-point sourcey or flat?

Sometimes you could, sometimes you couldn’t. If Cromwell’s at his desk and we had a desk candelabra with three or four candles, we would position it where it gave a nice soft light on his face and also looked correct.

It was very tricky to convince the authorities to let us use candles. Of course, these are buildings where candles have been lit for 500 years, but you get to the 21st century and all of the sudden it’s a big problem. We had a Fire Marshall in every room. We had a conservator from the location present when we were filming, whenever we lit candles. All the candles had to be 1-1/2 or 2 meters away from every wall or surface, so there were quite a few restrictions and it was a constant process of negotiation. But fair enough, they’re guardians of priceless properties and we had to respect that.

I didn’t want to tell the actors how or where to hold the candles. I said to them, “Look, just use the candle as you would if you were walking through this room at night in the dark.”

In fact, sometimes it was so dark you could not see at all. I was standing halfway down a stairway waiting for Mark Rylance to come around the corner holding the only source, which was a candle. He couldn’t see without it. We just wanted it to look as though I had just dropped in with my camera and Cromwell was woken up in the middle of the night and here he was with his candle. But in fact, that scene is one of my favorites, with the people lit in a way that looked exactly like the paintings we used as reference.

Sir Thomas More. By Hans Holbein the Younger. 1527 Oil on oak. 74.2 × 59 cm (29.2 × 23 in) Frick Collection, New York

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex. By Hans Holbein the Younger. Oil on oak panel. 1532-1533. 78.4 × 64.5 cm. Frick Collection, NY. (other version in the National Portrait Gallery, UK)

Mark Rylance as Thomas Cromwell. By Gavin Finney, BSC. Photons on Alexa sensor. 2014. 1920 x 1080 ProRes 444. From “Wolf Hall” series on BBC and Masterpiece Theatre.

Speaking of paintings, the Thomas More character looks pretty much like the Holbein painting.

He’s just a brilliant actor, Anton Lesser, as Thomas More. Mark Rylance doesn’t look particularly like the real Cromwell. The real Cromwell was much beefier, squarer, with a bigger head, but when you’ve got an actor like Rylance, you don’t worry about those things. There’s a scene in episode 3 where Cromwell is being painted by Holbein. We emulated the Holbein painting of Cromwell. We’ve exactly set up the background and the table that Cromwell is sitting at, lit it, and matched the lighting to the painting.

This is a a different side of history than what we saw in “A Man for All Seasons?”

Exactly. We have kicked up a lot of debate. “A Man for All Seasons” was a fiction. It was written by Robert Bolt and had Thomas More as the saintly moral figure and painted him in a very attractive light. But it’s also a fact that he personally prosecuted and ordered people to be burned to death, so there are two sides to every coin. It even became distasteful to Henry VIII. And Cromwell was no saint, for sure. I think Hilary Mantel’s stories take it from a different perspective.

The interesting thing about Cromwell as a character is that he’s the first plebeian powerbroker. He was the first person who wasn’t Aristocracy or Clergy to become that powerful. The son of a blacksmith, he became the second most powerful man in the country. To get to that do that in those times you had to be pretty remarkable.

Getting back to paintings, I’m thinking about artists whose scenes depicted candlelight. There’s Georges de La Tour.

Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Later on, Joseph Wright of Derby, who famously did a number of scenes by candlelight. And Gerrit van Honthorst: many of his paintings were single candle source.

Where did you get the equipment?

The cameras and lenses came from Take Two Rental House in London. It was a 17-week shoot. Another reason for choosing the Summilux-C lenses is that they’re considerably lighter than any others. When you’re holding the camera at 10 hours a day, that makes a difference.

The ALEXA’s not exactly light weight.

Once you add the battery, a high definition wireless transmitter for video assist, the Preston focus motors, mattebox, ND filters, and all the other bits onto the camera, you’re looking at 15 to 17 kilos, 32 to 40 pounds.

That’s ARRICAM weight isn’t it?

Yes, it’s quite a chunk. I’m not a keep-fit fanatic, but I hired a trainer for a month before the shoot to get into shape.

The main thing is getting tired, and if you’re not in shape you can injure yourself. Amazingly that didn’t happen. I did 85 days of handheld and at the end of it I was absolutely fine. We started in the beginning of April 2014 and finished at the beginning of August.

Six-day weeks?

No, five-day weeks and 10 hours on camera plus 1 for lunch, 11 hours total. That’s normal and sensible—more and more productions are doing that now. And more crews are refusing fortnight shoots, or 11/12-hour days.

The difference is palpable. It’s extraordinary. At the end of our 17 week shoot, the crew was in A1 shape. Everyone was happy, fit, no one was tired. On my next job we did a 6 days a week on a six week shoot, and the crew was wrecked by the end. It’s completely counterproductive. On our 17 week shoot we never went behind. We kept on schedule and we wrapped exactly at the right time with no pickups.

Did you have any zoom lenses?

We had a 45-250 and 15.5-45 ARRI Alura zoom. The 15.5-45 is hand-holdable and the 45-250 we used on the rare occasion when we needed to go long on exteriors.

With all that handheld work, what did you have for mattebox, handles, shoulder pad, and so on?

We had a clip-on mattebox most of the time. Blue modular standard handles. We found that ALEXA’s own shoulder pad was uncomfortable for these long periods of handholding because it’s quite hard and narrow. So we ended up taking everything off the base of the ALEXA. What remains is the camera’s broad base and I used a Camera Comfort Cushion, which is an excellent American product.

I’ve got the large, wide version. It has inserts so you can change the foam or plastic inside. That went on my shoulder and then the camera went on top of that. There’s a little strap that goes under your arm.

I also used the Easyrig. Certainly for most of the shots where I’m not moving too much, I had the Easyrig. It is a huge help. It distributes the weight like a rucksack and puts it on your hips.

It’s great. If you are being a mobile tripod and have to move around, and definitely if you have to have the camera low down, which we often did, it’s invaluable.

Were you able to do small, subtle moves?

Moving moving around, I used the Flowcine Gravity One with the Easyrig for moves. It is designed to take some of the whip out of the Easyrig. It’s a passive stabilizer, so it simply uses gravity and ball bearings and inertia to reduce the movement on the camera. It was quite useful. If you want to tilt the camera up or down the Gravity One lets you move the camera easily. I think that the best way you can walk smoothly with the Easyrig is with something like a Gravity One.

You have to remember that the Easyrig is a back-saver, not a stabilizer system. When you walk, because it’s on your hips, the post that goes up and over your head moves and sways the string and pulls the camera. If you’ve got the camera down low it’s a little easier. There are accessories like the Flowcine Gravity One that help this.

L to R: Chris Reynolds (1st AC), Gavin Finney BSC with Easyrig, Peter Kosminsky (director).

Kino Flo Celeb 400 powered by batteries. ARRI Alura 15.5-45 mm zoom.

So it’s not like a Steadicam?

It’s nothing like a Steadicam. And we didn’t want to be that smooth, though. Peter actually didn’t want that very fluid look because, again, it’s kind of a modern thing and he just thought it would step out of the style we had. In the end, the easiest thing for me was just the camera on my shoulder for most of the moves we did.

But I’d say certainly the Easyrig is a back saver if you are doing a lot of handheld. I use it a lot.

It was also good just having the camera on my shoulder, because one of the things about lighting with candlelight is that the lens-camera combination sees significantly more, I would say twice as much, as the eye sees at night. So I could light by looking through the viewfinder.

Talk about lighting through the camera?

Lighting at such a low level is really hard. It’s equivalent to the difficulty of lighting at ASA 25 in the Hollywood 1960s era where you had to squint through a pan glass to try and see how the film’s contrast might look. It was an art that you learned as a cinematographer. Lighting night-time light levels at T1.4 is also really tricky. I often would have the camera on my shoulder as I was walking around the room lighting, positioning the candles, because you couldn’t do it with your naked eye.

You’re using the camera as a finder, or rather, as an on-shoulder monitor?

Absolutely. The only way to see the lighting was through the Electronic Viewfinder. To give you an idea, there was a scene that we shot with candlelight at night in a hall at Berkeley Castle. At one point, real moonlight came through the windows, and I had to flag the moonlight off because it was too bright. It was actually throwing my shadow on Mark Rylance as he went across my path.

I told the gaffer we needed to get some floppies out and flag the moon. He thought I was joking. Then I showed him the image through the finder camera and he said, “Oh my gosh.” That gives you an example of the light levels we were working at.

If you were shooting wide open at T1.4 for most of the night scenes, you had very good focus puller?

I’m glad you mentioned that because it’s all very well for the DP to be saying, “Okay, right, we’re going to shoot T1.4 at 1600 ASA, handheld, no marks.” That was often the case when we came into a wide room and couldn’t put marks down.

We didn’t want to use marks unless we had to and the actors didn’t want to use marks. To me, it’s fine. But for the focus puller, they may go weak in the knees and say, “Hmm, maybe I don’t want to do this job.” But our “A” camera focus puller was a guy named Christopher Reynolds who’s actually from just outside Boston, an American who lives in Bristol, and I think is one of the most outstanding focus pullers in the country.

Absolutely extraordinary, and without his ability we couldn’t have done it. I don’t know how he did. He did have a remote. He used the ARRI wireless remote and a hi-def monitor, but his skill was extraordinary. We didn’t do that many takes and we hardly ever had to go again for the focus. Our 2nd AC Clare Connor even made up focus discs using luminous glow-in-the dark tape, so that Chris didn’t have to use a work light which would have been picked up by the camera.

Is he pulling focus off a monitor or just walking with you?

He was always walking with me using a monitor as a guide. The video assist was out of the room, usually a long way away. Peter was always in the room with the camera, so video village was just for costume, continuity and makeup. In the room, it was a small crew: that was how Peter liked to work. We just had the boom-op, Chris the focus puller, Peter, and me. That was it, along with the actors. So there wasn’t a load of paraphernalia.

There’s a scene in the end of episode 2 when Wolsey is arrested. It’s at night and we follow Wolsey and Stephen Gardner through a hallway, which is only lit by firelight. We go through a dogleg passage and into a room. Wolsey turns to camera and has to be sharp. I’m 2-1/2 feet away from him. Imagine, there are two actors, then there’s me, then there’s Chris trying to see what’s going on, and Jonathan Pryce turns to camera and he’s pin sharp. I have no idea how Chris did that. I remembered just looking through the viewfinder knowing how shallow that depth of field was and Jonathan turned to camera, bam, his shot was incredible.

The camera was an ALEXA Plus with wireless receiver built in?

Exactly. And we were just using SxS cards. It was normal HD 16:9 and we didn’t shoot 2K. It really holds up well. We screened “Wolf Hall” at some big cinemas in London, we screened it at the BFI Screen, and it looked amazingly.

How did you handle data? DIT?

Not in the same way as an American show would. I tend to slim all of that down. I’m not interested in lookup tables and loads of processing. I do grade, though. We have a DIT, Rob Shaw, and he looks after the data and the cards. He will take the cards, clone them so we’d have one clone on the truck, and then he would do another clone drive or the editors. The editors would clone that drive — so there would always be three copies. Rob also does the transcode to DNxHD 36 for Avid editing. We used Davinci Resolve to put a rough grade on it, as well as a Log C to Rec 709 LUT, which was the only LUT I used. It’s pretty subtle. This is done on the camera truck, at lunch.

We’d have an hour for lunch, so I’d have half an hour to eat and then we’d spend 20 minutes going through that morning’s and the previous day’s rushes. If there was time, I’d do it at the end of the day as well. If I needed to look at the saturation or balance two cameras, or put in a bit more contrast, I’d do that.

The ALEXA seems to be very sensitive to green, so if you’re shooting outside in England there’s a lot of green and I find that distracting. Quite often we do a secondary color correction on the greens just to calm them down a bit. I do that on everything now, so when it goes to the editors it’s pretty close to what I plan to do in the online grade. Obviously not as finessed, but it’s in the ballpark so that everyone—Editor, Director, Producers—they’re all seeing what I intend to do in the online.

In summary, the SxS card comes out of the camera, it goes to our DIT, he copies the SxS card to a RAID drive, makes another copy which will be a shuttle drive that goes to the editors, and then the editors will make two copies of that shuttle drive. They’ll keep one and the other one goes to the post house.

And which one are you correcting?

I’m only correcting the transcode that goes into the Avid as DNxHD. The actual Log C clone is never touched. That stays untouched, cloned from of the SxS card.

Rob did his QC of the data and a visual QC for any focus problems or other anomalies. Our assistant editor would do a similar technical QC. Once we had the editor and the DIT sign off, then we’d recycle the SxS card. We usually wait a three day cycle to re-use the cards.

And then for final grading?

It’s in my contract that I’m at the grade and it is paid for. Every job is that way. I won’t do a job if I can’t do the grade. The grade is really critical to me. It’s a very important piece. Less for what you can do, but more for what can be undone if you’re not there.

The grade was done at Lip Sync. It was done on a Baselight and the colorist was Adam Inglis, who’d just done “Mr. Turner” prior to our job, photographed by Dick Pope, BSC. He’s a really great colorist, very much like a film grader, very subtle, doesn’t overuse all the tools. But there were quite a few scenes in big halls where we needed to bring the walls down in certain areas that were too hot and I couldn’t flag things properly. He was very helpful and sympathetic in the way that he put in shapes and windows just to bring areas down that I couldn’t control on the day.

You had DaVinci Resolve on set for dailies, but Baselight for the final grade?

Yes. We had 13 days for the grade, for all episodes, 3 days for the first episode and then 2 days for each episode after that.

You take frame grabs while shooting?

They’re frame grabs out of the camera, yes. They are TIFs from the DPX frame grabs, and I take loads. I wish it were a little less clunky on the ALEXA, but I love its ability to do frame grabs. It’s very useful for me because at the end of a shoot I’ve got a stills library. I can actually start playing with those images in Lightroom. If I can’t make a grade or miss a day, I can send those pictures to the colorist. And even if I am there, they’re very helpful as a starting point. I’d often send these frame grabs with a grade on them to Peter at the end of the week to give him some idea of the way I was going to go.

I’ve got 1218 stills from “Wolf Hall” just by hitting the frame grab button during the shoot. They write to an SD card in the camera. And the DIT copied those off each day onto a thumb drive for me to take and then put them into my computer. They’re really helpful.

This is a fascinating story. It has a nice combination of everything we like, art, equipment, technique, technology.

It was a remarkable place to be and we had amazing weather in the summer as well, unusually for England, so even that was on our side. We tried a lot of old techniques, using candles, and it is a straight line from “Barry Lyndon,” isn’t it, which Kubrick did beautifully with double wick and triple wick candles, fast film, and NASA lenses.

If Kubrick had ALEXA and the Leica Summilux-C lenses on “Barry Lyndon” he’d have been a happy man.

It’s great to have what this technology allows you to do, and in a way it lets you be even more real to the drama. I think that’s what’s interesting. We didn’t use smoke in any of the scenes, we didn’t fill the places with shafts of light, we didn’t use lots of filters on the camera. I just wanted it to be very real, very immediate, in a contemporary way, filming a period drama rather than just plugging in all the things you normally do to make it look period. It may have ended up in the same place, but it was a different approach.

I think you ended up in a totally unique area. You started with a story, a concept, decided on the look, and then you found the tools to do it. But once you chose those tools, do you think you were able to take it even further and shape the story to fit that kind of technology?

Exactly. And that’s how I like to use technology. I think what we have is an amazing array of tools at our disposal. The thing is not to be led by the tools, but to be led by the story and that’s why going back to the beginning, everything was driven by the drama, and the locations, and the technique the director wanted to use. That’s where your starting point is. You start to look at what tools will crack those problems. How do we shoot handheld at night? How do we work in grade-one listed buildings? How do we make it look as it looked then? How do we shoot unobtrusively? How do we give the actors freedom to move, not tie them down? And then you say, okay, what tools will make that work? And we’re very fortunate that we have a whole load of things to play with and it’s great to find the right tools for the job.

This is the best article I have read in your journal! It is so informative and intuitively right, you never want it to end!