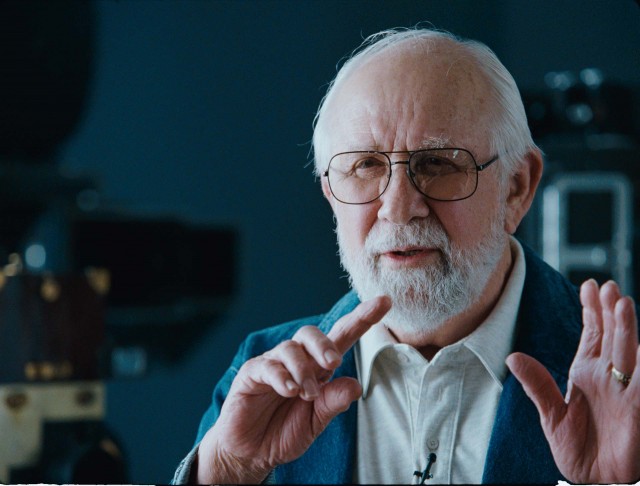

William A. Fraker, ASC, BSC passed away last week at the age of 86. ASC President Michael Goi said, “He will be missed but never forgotten.” ASC president emeritus Richard Crudo said, “”Billy Fraker was the epitome of a Hollywood cinematographer.”

Born September 29, 1923 in Los Angeles, Fraker attended USC. He went on to compile an impressive list of credits (Bullitt, Rosemary’s Baby, Heaven Can Wait, WarGames, The Freshman) and six Oscar nominations. In 2000, he returned to USC as a highly popular professor and mentor.

The picture above is a framegrab from the William A. Fraker interview conducted in 2005 by Jon Fauer and Bob Fisher for Cinematographer Style. Here’s an excerpt of the complete transcript from the book.

Tell us who you are and what you do.

I am William A. Fraker, ASC and also BSC, by the way of an honorary membership in the British Society of Cinematographers, which is quite an honor, but mostly it’s a great honor to be part of the ASC, the American Society of Cinematographers.

How did you become a cinematographer?

I became a cinematographer because of my grandmother’s influence. She was a schoolteacher in Mazatlan, Mexico, when a young revolutionary by the name of Pancho Villa was coming down through the north. Because she was working for the federal government — and Pancho was starting the revolution and hanging people who worked for the government — my grandfather and grandmother, with my mother and my aunt, who were 1- and 2-years-old, respectively, left Mazatlan. They ate two meals and walked to Los Angeles.

When they got here in 1910, my grandmother went to work for Monroe Studios in downtown Los Angeles, at 7th Avenue and Broadway, as a photographer. Eventually, she opened her own studio, and when I was in junior high and high school, I helped her develop glass plates. There was no plastic film in those days, just glass plates with emulsions on both sides. That is how I learned the basics of photography. My aunt, who along with my mother, was an extra, said to me one day, ‘Billy, you’re going to go to school and you’re going to become a cinematographer.’ I asked what she meant and she said, ‘They’re the most respected people on the set. They all wear ties, and it’s a great profession.’

When World War II came along, I quit high school, went to the service for four years and came back and went to the University of Southern California’s cinema school because of the G.I. bill; otherwise, I couldn’t have gone. I was making $75 dollars a month, which was a lot of money in those days. The reason I followed my aunt’s advice to be a cinematographer was because when I went to the movies and saw those gorgeous images up on the screen, I wanted to do what they did — they being the cinematographers. My interest was furthered by a desire to re-create those images. There were some great cinematographers in those days.

Did you have any mentors at USC?

Definitely. I was there during probably one of the most prolific times in the history of the film school. It was right after the war and Slavko Vorkapich, who was the father of the montage, headed the cinema division. The last year and a half at USC, I went five nights a week, because the night classes, which were called the extension courses, had the best teachers, most of whom came from the industry. They gave us real knowledge of what the motion picture industry was all about.

When you walk onto a set at the beginning of the day, what goes through your head?

The most exciting part of walking on the set in the morning is that it’s really inspirational. It’s completely black, and I strike my first light for what I’m going to do and that becomes my first brushstroke. Then I add other brushstrokes along the way, different lights and so forth, until I come up with a complete picture. Then I look at it and say, ‘OK, let’s do it.’

How do you come up with the style of a particular film?

The look of a picture is inherent in the material. I read the script and say, ‘This is what I feel this picture should look like.’ Then there’s dealing with the actors, the director, the studio and the producers. Basically, I have an idea of what I want my picture to look like — I call it mine because I’m working on it — and I talk with the director. It’s usually me and the director who find a bond and form a marriage. When I talk to somebody whom I’m married to and they say ‘no,’ and I know that they really mean ‘yes,’ I learn about people’s psyches and how to deal with them through that relationship.

The marvelous thing about being a cinematographer and about being part of Hollywood is that I’m working with different people and different psyches all the time, so I learn about people and their movements, what they really mean, whether or not they’re paying attention or if what I’m saying is really getting to them. Sometimes, we as cinematographers have to take that leadership role and put it up on the screen. We have to remember that it’s a visual medium and we’re telling a story up there.

You’re in the enviable position of going back to your alma mater and teaching the next generation of filmmakers.

It’s a marvelous feeling to go back and teach. And USC is one of the few cinema schools renowned throughout the whole world. That’s all because of Woody Omens, [ASC,] a marvelous cinematographer who left cinematography to become a professor at USC. He asked me to come as well since I was part of USC during the good days.

The only two really good cinema schools after World War II were USC and New York University. So now I’ve gone back after all these years, and it’s marvelous there. When I first attended, I met Jack Crawford, who was a compatriot, and Connie Hall, [ASC,] and Harry Kirshner. And as I said before, it was all headed by Slavko Vorkapich, who was a great special effects man as well as being the father of the montage. He did pictures like The Good Earth and San Francisco, which had a great earthquake sequence. He was responsible for teaching us to think visually.

And that’s what I try to teach these students at USC. I have them do five 5-minute films without dialogue. They have to express themselves and tell a narrative story, beginning to end, completely in the visual medium. It’s a marvelous experience for me as well, because, believe it or not, I learn so much from these kids. When these students were 6-months-old, in diapers, crawling across the living room carpet, the television set was on. It’s their medium. Then came the electronic world, which brought a renaissance. First sound came in and created a complete revolution that changed the history of Hollywood. That’s why soundstages are built today. Then television came and changed many aspects of making motion pictures, like having more close-ups.

Now we’re in this electronic world, with digital photography coming in, so there have actually been several renaissances in the industry. And it will continue to change. How many pictures have been made since the invention of motion pictures? A million? And no two pictures are the same. And though the situation changes every 30 or 40 years, the way motion pictures have been made for the past 120 years has not changed. There are still grips, electricians, actors, makeup, writers, directors and cinematographers.

Do you think the role of the cinematographer will change?

I don’t think the roll of the cinematographer is ever going to change, because somebody needs to tell a visual story. I’ve worked with cinematographers like Ted McCord, [ASC,] who did The Sound of Music and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. He said he would spend an hour and a half on the backgrounds and three minutes lighting the actors, because he knew how he had to light the actors — as movie stars. How do we make a 35-year-old woman look like she’s 22? We have to do it with lighting, and that’s what we’re trained to do. We set the mood of the whole picture with the background. If it’s a mystery, it’s down; if it’s a musical, it’s up. So we’ll always need people who are trained for this. You can’t just say, ‘I’m going to take Sophia Loren to a nightclub.’ The next day, they’d see the dailies and you’d be gone. We have to light our stories properly to tell the story visually.

Pingback: William A. Fraker, ASC, BSC | Shot On HD