Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC, GCA and Sony’s Tanya Lyon were in New York for a pre-release screening of A Complete Unknown. (It opened on Christmas day.)

We meet at a favorite restaurant—Sistina, across from the Met Museum. Storaro likes the table in the back corner of the back room where the light is always beautiful. Skylights above make it just so. Begin with Beets and Burrata, Tuna Tartare and Bresaola with Artichokes. Next, try Nantucket Bay Scallops, Linguine with Clams and Mussels and Fettuccine Integrali with Black Truffles and Crab Meat.

But I digress. We’re here to discus Phedon’s latest great work as cinematographer on A Complete Unknown. Phedon is hardly unknown. Credits include Ford v Ferrari, The Trial of the Chicago 7, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, The Monuments Men, W, 3:10 to Yuma, Sideways…

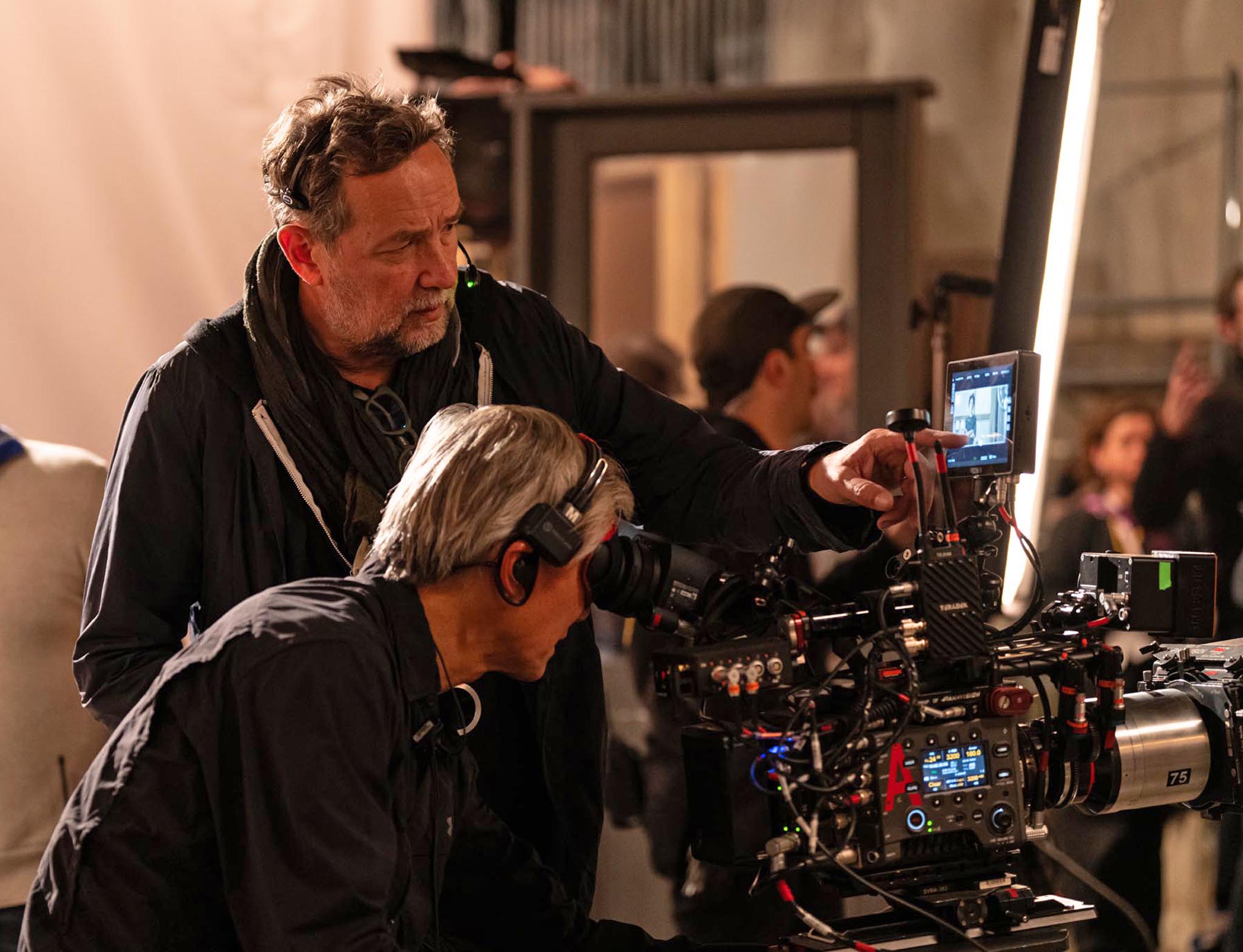

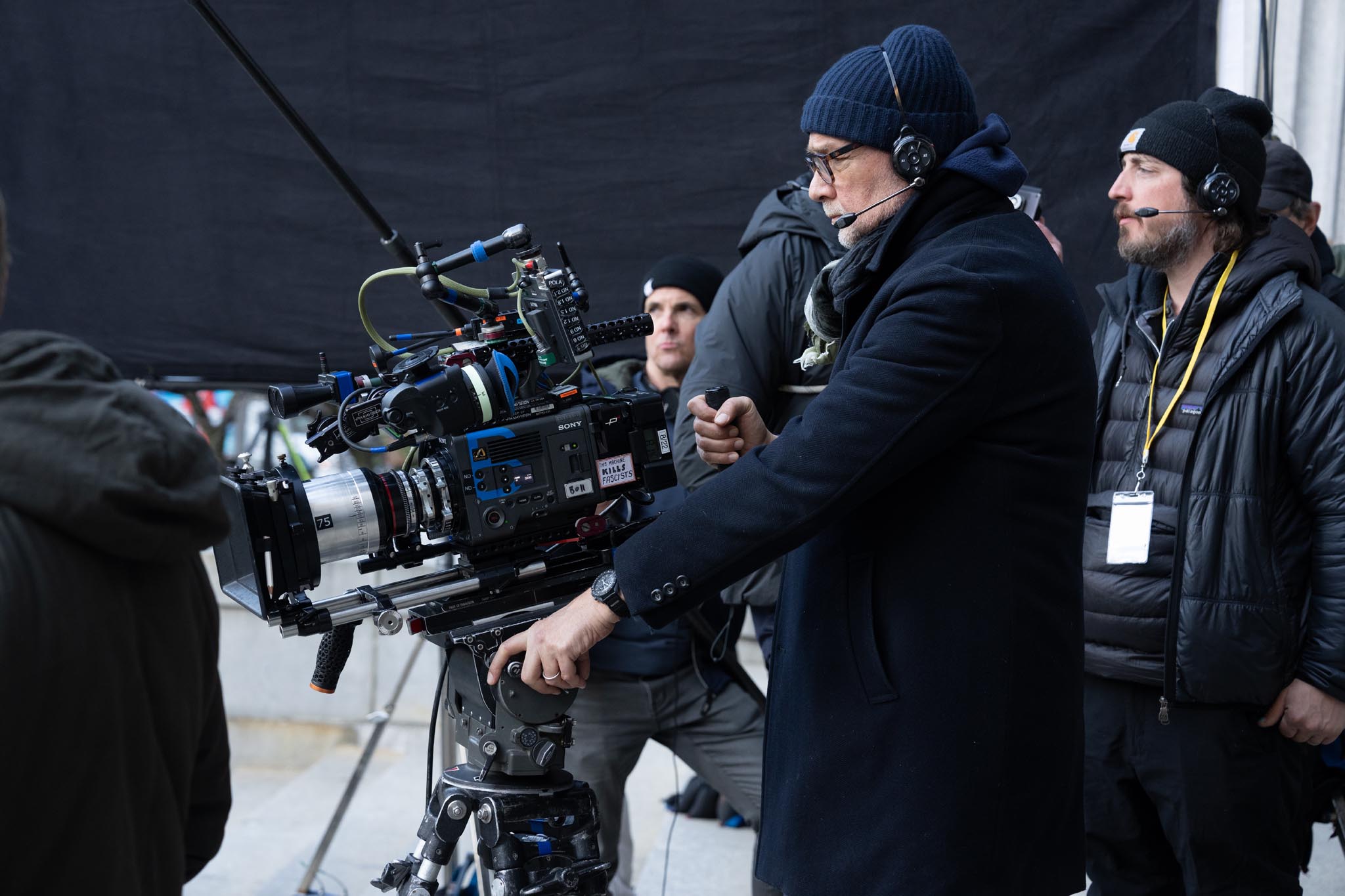

L-R: P. Scott Sakamoto, SOC (A-Camera/Steadicam operator), Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC, GCA, James Mangold (Director). VENICE 2 camera, Panavision Anamorphic. Preston Light Ranger, Teradek Bolt, Sachtler 9+9 head. Photo: Macall Polay, SMPSP.

Jon Fauer: Congratulations on “A Complete Unknown.” It is one of my favorite films of the year.

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC, GCA: Thanks. This is not your typical biopic. Director James Mangold had a series of meetings with Bob Dylan. He was in complete approval of everything we did. One day, they were in a café to discuss the script. At some point, apparently Dylan asked, “So what’s this movie about?” Jim replied, “It’s about this kid who grows up in a small community in Minnesota, and he feels suffocated and he moves to New York where he finds a new family and makes new friends and then he feels suffocated by them and he runs away from them. And Bob goes, “I like it.”

It’s important to remember that Dylan was about 20 years old when he came to New York. He was discovering things and being affected by the spirit and the vibe of the sixties, the village—reacting and inventing himself and changing as he did throughout his entire life, not just where this movie ends in 1965.

The five years we cover in our movie is about this kid, who is an incredibly gifted writer and poet, becoming so popular so quickly. People are trying to have him belong to the folk music movement but he just wants a band. He wants to be a rock star. There are some nice scenes in the movie where you see Johnny Cash on stage and Bob is checking it out: oh, he has a bassist, he has a guitarist and a drummer and there’s that nice reaction shot where he is listening to Cash in the wings and he’s taking it in. He wants a band. He doesn’t want to be the guy with a harmonica and an acoustic guitar the whole time.

How did you get started on this job?

It’s based on the book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, by Elijah Wald. The film originated a while back. We were talking about it five years ago, even before we did Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. And then Covid hit. But Timothée Chalamet was committed and that was one of the reasons we were going to do it. He was already learning guitar, practicing and rehearsing songs for a long time. Then we came back in 2023 to scout the locations. They were starting to prerecord Monica for Joan Baez and Ed Norton for Pete Seeger. And so everything came together. Arianne Phillips was ready with warehouses full of wardrobe. We had stages ready to be built. And then the writers’ strike came. So we shut down again. We returned in the spring of 2024.

There’s a nice progression to the looks.

We wanted different looks for the film. For his first arrival in New York and the MacDougall Street exteriors, we embraced grayer, more muted tones as he comes in his shabby clothing, guitar case and backpack. The summer scenes and the Newport Folk Festival were done at the end June with hundreds of extras in T-shirts and summer clothing. We wanted to get a spectrum of seasons because the movie takes place over five years. But it’s also something that happens visually, from where he’s the young man who has just arrived from Minnesota and his journey to becoming Bob with the Ray-Bans, motorcycle and leather jacket, and then the orange shirt and polka dots. As we moved into the summer, everything becomes more saturated. The elements in the frame also changed as his character develops.

How does your lighting change?

The lighting inherently changes because it goes from dingier, darker, smaller clubs like the Gaslight with just a few very warm tungsten bulbs to bigger venues, Carnegie Hall, and then to Newport. As he performs in bigger venues, it’s harder lighting and I used all period stage lighting. I wanted a very natural approach. I also wanted the streets not to look lit. And that’s one of the reasons I chose to use the Sony VENICE 2 cameras. I had tested them at higher ISO ratings of 6,400 and even at 12,800. Jim Mangold really liked the idea because, in conjunction with minimal lighting, I said that I would like to shoot at a deeper stop.

When you have Large Format digital cameras, you can get beautiful bouquets [of bokehs] with out-of-focus lights. But on this film, I wanted to feel the textures of the city with depth of field that was not too shallow. Typically with Jim, we shoot our closeups on a wider lens. I would say 90% of A Complete Unknown is shot on a 40mm anamorphic that has very close focus abilities. Dan Sasaki at Panavision built us Full Frame custom lenses based on B Series and C Series front elements, with the mechanics of T Series. So they have the close focus of T Series anamorphic, but they have the specular flare characteristics of the older glass.

We liked to be in extreme closeups for the performances, not isolating the characters and feeling the environment, feeling the background. When he’s walking down the streets of New York, I wanted to see the brownstones, I wanted to see the period cars, the extras, the fire escapes. I was able to use a lot of the existing urban ambient street lights. Often, I would just eliminate lights rather than adding them, wrapping lights we couldn’t control. We also took advantage of wet downs and some steam.

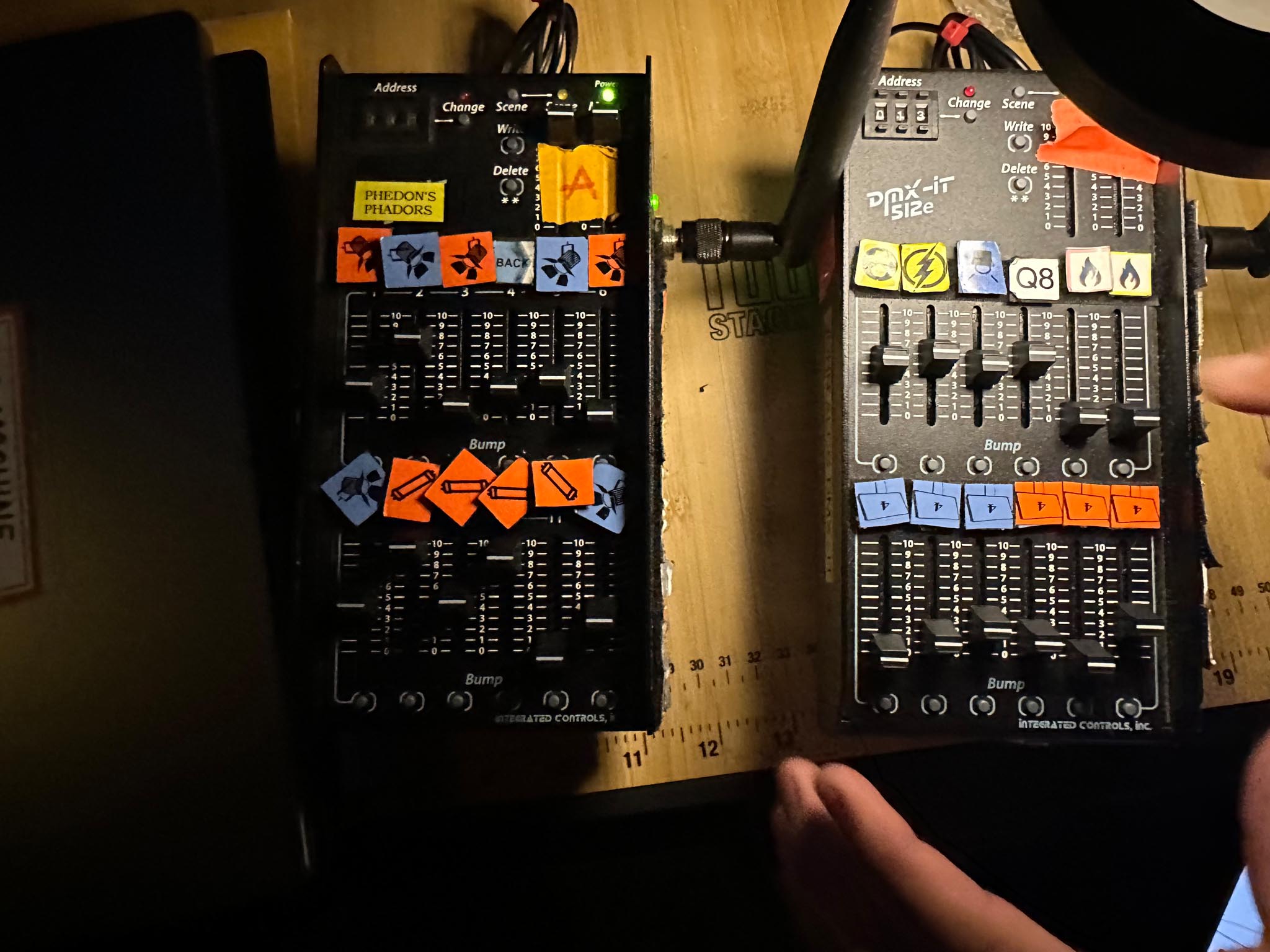

We had tiny eyelights, which were Rosco DMG Lumiere DASH fixtures with small dome diffusers that attach magnetically. Electricians walked with them to just augment the natural light when necessary, and sometimes it was not necessary at all. They can be quite punchy if you want them to be, and I could control them with wireless DMX.

For example, on night exterior Steadicam shots, two electricians would be walking down the street with these DMG DASH fixtures on the left and right side of camera operator Scott Sakamoto. Battery powered, no cables. I had a DMX-it, which is a 12-channel mechanical slider control panel. Looking at the monitor, I could add a bit more augmentation when he is walking past a red neon storefront and then fade it out. I can switch keys. I avoided tube fixtures and snap-on grids because he’s wearing glasses all the time and you’d see the reflections of larger movie lights. But the DMG DASH fixtures don’t really look like movie lights even if you catch them in his Ray-Bans at night.

Do you also have a big dimmer board and operator?

The way I work in general is to be at the DIT cart with the monitor and our viewing LUTs and my DMX wireless dimmers there, but I also have a dimmer board operator nearby where I can see him and discuss things. He’s also programming my small DMX-it board so I can have the freedom to pick it up, walk onto set, change levels even during the take, on the fly, sometimes actually shifting keys. It’s almost like being a sound mixer going from one boom to another, except it’s with lights.

Here’s another example. Bob is coming up the stairs, looking left to the ground. I have a light there and kiss him a little bit with that. Then he turns, looks right and walks down the hallway. I get rid of that fixture and I bring up the other one. It looks very natural, because working at these high ISOs, it works. Night exteriors are at T8 ½ or T11 stop. Mangold asks, “What stop are you on?” I reply, T5.6 or 8.” He’s like, “What ISO?” I go “6,400.” He says, “Why are we not 12,800? You told me it’ll be fine.” I go, “Yeah, it’s fine, but I don’t really need it. I’m okay with the T5.6 1/2.” He says, “Go 8 ½.”

Is he pretty technical?

When I sell him something, he picks that up pretty quick. He is an excellent still photographer and works on his photos. He has a very specific taste in terms of contrast and saturation, which is why our reference photographers were Eggleston and many street photographers of New York in the 1960s. That’s part of how we built the LUTs with David Cole at Fotokem, basing the looks on still photography of the 60s.

It reminded me of Kodachrome from the 60s.

That was the intention: a certain shift in the blues and a little cyan. And the reds are really poppy. They walk past a Kodak sign and its very saturated red affects the skin tones. So that was the idea. But once you give Jim a reason why you’re doing something, he’ll embrace it.

Another example: when I suggested the VENICE 2, he asked, “Why are we shooting with a new camera?” I replied, “Because we can shoot it this fast. I’ve tested it. It’s not noisy at 12,800.” And, of course, I was still nervous at first. I projected footage in New York on a big screen just to make sure. But I was also reassured knowing that we’d be doing a SHIFTai at Fotokem. (SHIFTai is an analog intermediate: graded digital files “printed” to film with an ARRILASER film recorder onto Kodak 50D 5203 negative, and then scanned back to digital.)

We pick up natural film grain qualities, but we’re not doing this just for the grain. As Ed Lachman has said, colors react differently once it goes onto negative film.

The workflow is traditional, as you would normally do a DI. You have all the tools of DaVinci Resolve, including power windows, and then you laser it out in an optimal way to the negative. We tested various film stocks and liked 5203 best. And then, when you bring it back into the DI, you still have some wiggle room to make some minor corrections before you make the DCP, but we had almost no corrections once it came back from film.

What about dailies?

We had a film emulation for editorial to work with. I always try to get as close as possible to my final look because the director and the editors live with this material. It becomes their norm and they get used to it. So it’s very important to me that I get it as close as possible to the look that we’ve I spend a lot of time finding in pre-production. During the day, I make adjustments to the LUT and send instructions for the dailies colorist to match. And to ensure that everybody sees the same thing, we calibrate the monitors in editorial. These things accelerate the DI process.

Even though you were sometimes shooting at 12,800 ISO, I didn’t notice any noise on the big screen.

There’s no noise. That’s why I shot with Sony VENICE 2 cameras. And, because I wanted to shoot with vintage lenses, I didn’t want to use them wide open. I wanted to close down to at least T8. It’s a picture with about 100 locations over 60 days, with multiple company moves at night in Hoboken. I wanted to keep the equipment minimal and treat it almost like a documentary. In the recording studio and on stage, there’s really no additional lighting other than period practicals and some very small sources. Sometimes it was just a PAR can bouncing off the ground. I like using tungsten.

Tell us more about the lenses.

You might recall that on Ford v Ferrari I decided to go Large Format, and I didn’t want to just do the 2.39:1 spherical aspect ratio. I wanted to shoot anamorphic. At the time, the traditional Panavision C and T Series didn’t cover the ALEXA LF sensor. Dan Sasaki courageously offered to expand a set. I think this was first time it was done. We went into production on Ford v Ferrari using essentially prototype lenses with very specific characteristics like vignetting at the corners and focus fall off. They had interesting C Series flares and they looked great. This was my go-to package that I subsequently used on The Trial of the Chicago 7, on Daddio and other projects. These lenses became quite popular. Panavision then started converting and expanding a lot of their beautiful classic C Series, B Series, G Series and T Series anamorphic lenses for the larger format.

For A Complete Unknown, Jim and I wanted to back away from the classic Hollywood Panavision anamorphic formula look and try for something a little bit rougher.

“It’s going to be darker, less high-key, more moody, with different flares, warmer flares and a bit more character,” I said.

Dan goes, “Okay, okay.” He built us series one of a set he calls hybrids—Full Frame anamorphics with the mechanics, close focus and size of the T-series, but with the vintage front elements of the B or C series. Please don’t ask me what he does because when you see his desk, there are glass elements everywhere.

He made us a 35, 40, 45, 50, 60, 70 and 100 mm. We mostly lived on the 35mm and the 40mm. Now, understand that when we say 40mm, it might be more like a 38mm. Once he expands them and does whatever he does, the focal length numbers can be different.

Does expanding the image circle degrade the image?

Perhaps. But, I didn’t see any. Going to film negative also takes some sharpness away. It’s not like he screws an extender onto the lens mount. Basically he changes the barrel, the rear elements and the calculations to cover the larger sensor. We were actually able to cover the entire Sony 8.6K sensor.

This is our seventh film together. Jim is very much in love with anamorphic lenses. Of course, I suggested trying something else, maybe a different aspect ratio or anamorphic squeeze factor. I even proposed black and white or handheld. We talk about these things. Ultimately, we do like our anamorphic frame. We like shooting closeups physically close with a wider lens. That’s our language. When I said to him that it seemed we were repeating things we’d done before, he said, “Well, that’s who we are.” Which is true.

Our sense of composition is not over-stylized. I’m trying to be natural in my lighting. Our camera moves are mostly on a dolly, crane or very precisely executed Steadicam. We’re not trying to distract with stylistic choices. I try to avoid anything that cries out “Filmmakers at Work.” I try to hone in on the performances, I want to see Timothy’s eyes. I want to be close. I want the audiences to be able to take in those incredible performances. I don’t want to overpower or distract with a visual language that takes you out emotionally. I feel fortunate that the set design, wardrobe, hair, makeup and the performances provide an abundance of opportunities to light and frame and I don’t need to force another layer of style onto that.

In her New York Times review, Manohla Dargis mentions “Chalamet’s shivery, ice-pick gaze.”

You feel it when you’re physically close with a camera. It’s not popping on a longer lens and it’s not an audience perspective. You feel you’re on stage with him and you feel the energy, but you’re also not isolating him because we do these rotations and you tie in the crowd and you tie in the people in the side wings. It’s very hard to fake performances like this. That’s why Tim Chalamet insisted on playing live because you feel it.

And we film, running through two or three songs without cutting. Scott Sakamoto is a great, instinctive operator and we are all just reacting. He did Maestro and A Star is Born, so he is very fluid with the camera. You can’t say to the actors, “Here’s your mark and here’s your mike.” With Tim, you want to capture all the physicality, all those emotions. You want to be close. You want to be wide to read the body language.

Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan, Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez, Scott Sakamoto on Steadicam with VENICE 2. Photo courtesy of Sony.

Were you mostly on Steadicam for the concerts?

It was multiple cameras for the audience. One was wide, one was on a 50-foot Technocrane that moved into a medium closeup or even a closeup. It would get in the frame of the other two cameras, but that was to shoot the crowd. Then we’d get on stage with a single camera—Scott on the Steadicam, and he would be doing 360 degree moves and I was live mixing, shifting key lights. When he was in back, I’d have a light down the center to make the rim lights glow more on Tim and Monica’s hair.

Was everything on location?

The apartment, Chelsea Hotel interiors and the Viking Motel interiors were set builds in a studio. Everything else was on location—all in New Jersey with the exception of the Chelsea exteriors and the NY downtown courthouse. We recreated MacDougall Street and the West Village in Hoboken because was a little easier and also bit less gentrified, with fewer trees. They planted a lot of trees in the Village in the eighties and now it doesn’t look anything like our 1960s reference photos. Francois Audouy, our production designer, did a lot of research and recreated the storefronts, the club interiors and also the apartment with the artwork, what’s on the mantle, his record player, espresso machine. It’s all very carefully researched.

How did you get into film?

I was born in Athens. My dad was a painter and also an art director and production designer. I grew up in Munich. I discovered film with a Super8 camera but was annoyed by its flimsiness. I bought a 35mm Nikon and became pretty serious about still photography. Then, I sent a bunch of photos to my dad who was working on Love Streams (1984), an American film directed by John Cassavetes. John wrote me a letter: “Your photography captures the spirit of a new generation in a classical form. Can’t wait for you to come join us.” I told my mom, “I’m not studying, let me just go to America for a year and check it out.”

Liz Gazzara, who was apprentice editor on Love Streams in New York, wanted to do a short film and asked me to be the DP. I never had a chance to go to film school and believe me, there were lots of mistakes. But I had discovered cinematography. Raoul Coutard’s work on the 1963 film Contempt (Le mépris) was the first time I really noted the name of the cinematographer. I wanted to do what that guy did. I wrote his name down even before I wrote down Godard’s. Then I started shooting short films, including UCLA grad films and for Alexander Payne. My film school really was working for Roger Corman. Since I had no training and little experience, I didn’t use a lot of lights or equipment and I was fast. So they liked me because we always got the day done.

These were 15-day features, using an Arriflex 35BL-2 and Zeiss Super Speeds, with Fujifilm stock that he got off the gray market in Hong Kong. I had shot behind the scenes on Barfly (1987) and discovered Robby Müller and Frieder Hocheim using fluorescent tubes to light the scenes (this was before Kino Flo officially launched), Janusz Kamiński, Mauro Fiore and Wally Pfister were crewing for me on those early Corman films, so we were all inspired by those minimal lighting tools, building our own soft-boxes, using fluorescents and being very expressive with mixed colors.

Did Raoul Coutard’s cinematography on Z (1969) influence A Complete Unknown” Natural light, documentary style?

All of the French New Wave had a strong influence of how I perceive cinematic storytelling. So no matter how big the film, I have a logical lighting approach. If someone’s backlit, and then I do a reverse, that actor has to more or less be frontlit. I’m not going to do everybody backlit just because it looks good. I try to apply this logic to the lighting directions and I try to motivate off of practicals, or even if you can’t see the practicals, it looks like it’s coming from a practical. I like mixing colors. I don’t need to correct every fluorescent tube or sodium vapor light. I’m fine with the dirty yellows and greens, like at the Chelsea Hotel, when Tim is silhouetted at the end of the hallway.