John Brawley and The Great

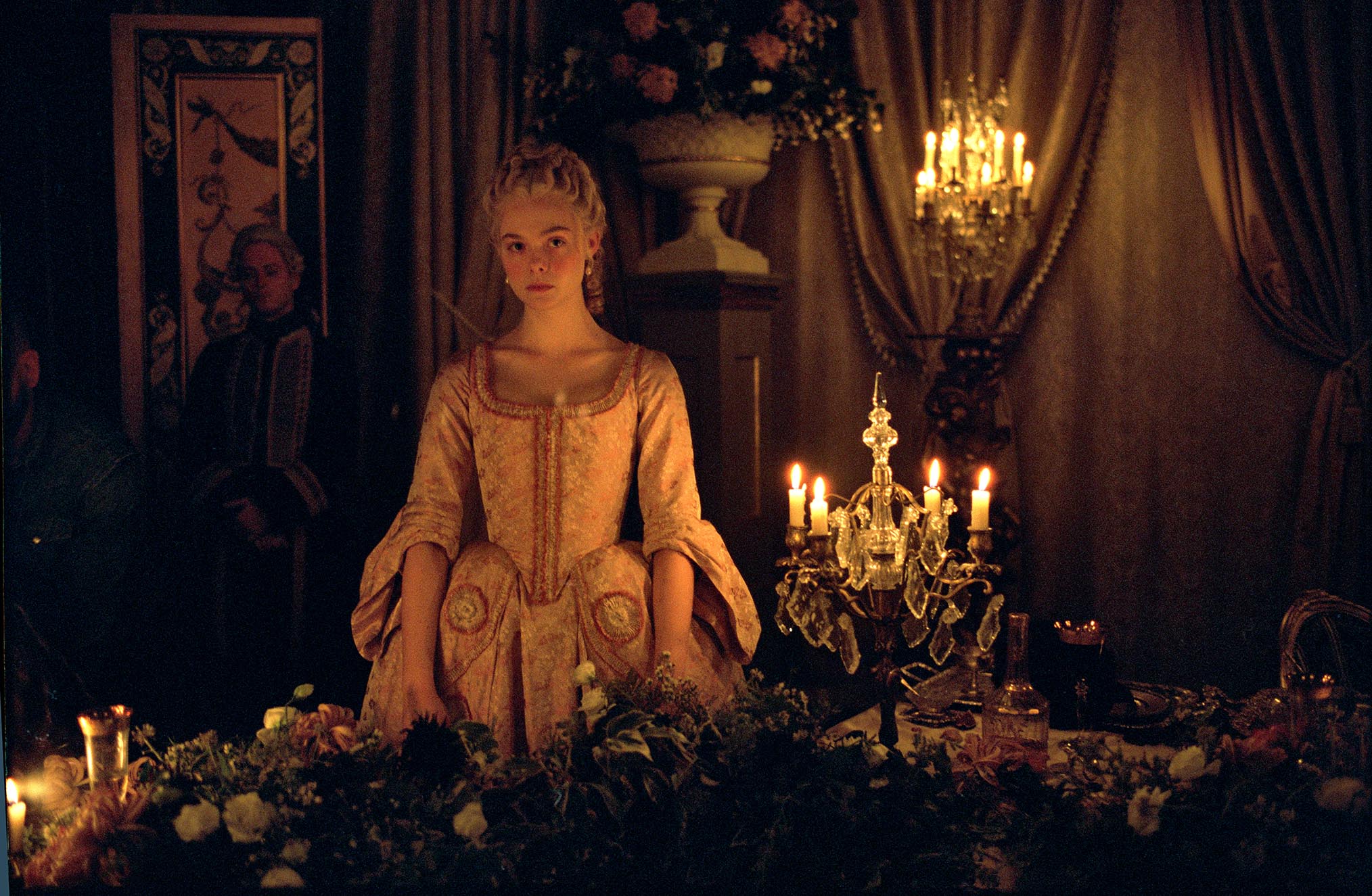

The Great is a bawdy farce streaming on Hulu, with Elle Fanning as the Empress of Russia and Nicholas Hoult as the Emperor. John Brawley was the cinematographer on 5 of the 10 episodes.

Jon Fauer: The Great looked great. “Huzzah,” as they often exclaim in the show. Would you please give us some background.

John Brawley: I appreciate that. We wanted to say to the audience, “This is not your normal costume drama, this is something else.” Tony McNamara, the creator, writer and producer, would often say, “It’s not a historical drama. It’s punk history, it’s anti-history.”

It even says at the beginning, “An occasionally true story.” And that’s really to take away your expectation that what we’re doing is telling anything close to a historical version of the truth.

Tony McNamara was also writer and producer of The Favorite. The Great might be pitched as The Favorite meets Animal House?

Tony described The Great as being about a woman who wakes up and realizes that she’s in a really bad marriage. And she’s living in something like an apartment block, which is what the palace is, with all the neighbors knowing her business and getting involved in it. That was the metaphor.

The idea is that this is like a frat house or a share house. It’s in bad condition. He told the set dressers, “There should be more broken stuff on the floor. There’s got to be more graffiti on the walls.” Yes it was a royal palace, but it was run poorly, it wasn’t kept well. There were food scraps in the corner.

He wanted it to be truthful even though it wasn’t factually correct. It was an attempt at an honest approach on what it was, not glamorizing it. Many of these period shows have perfect costumes and perfect staging. We wanted the imperfections, the rawness, rough looking, a bit haphazard and unplanned. That was some of the logic to it.

As an example of those imperfections, if you look at Count Orlo’s glasses, they’re crooked on his face; they’re not perfect frames.

We tried to be contemporary in the way we shot it, and the way we covered it. We wanted it to feel like you’re watching a contemporary show, but it just so happens that they’re wearing all these big, flowy dresses and they’re in a grand palace.

One of our unofficial rules was very few crane shots. There aren’t many big, swoopy moves compared to most costume dramas. We did not fill the sets up with smoke. In fact, we decided not to have hazy interiors. Admittedly, there’s a bit of natural atmosphere that happens because we’ve got 150 candles in the room, but we didn’t add any atmosphere to whatever was there naturally.

We’ll get to candles in a few minutes. But first, what camera and lenses did you use?

We shot with ARRI ALEXA SXT and Blackmagic URSA Mini Pro 4.6K G2 cameras, with Cooke S5/i and ZEISS Super Speed lenses.

The Great is a satirical piece. It’s kind of anti-history. Tony McNamara, the show runner, wanted something light in treatment. Not just in terms of visuals, but overall tone, which is really important. This is the fourth show I’ve done with Tony. He’s Australian, as well.

We talked about exploring options, cameras and lenses. Cooke S5/i are interesting lenses. It took me a while to get a grip on of where they worked really well. For the first two weeks, I was shooting at about T2.8. But then, I realized that I was shooting wide open at T1.4 with the actor about six feet away from the lens. All of a sudden, something magical happened. Unfortunately for my focus pullers, I was now mostly shooting wide open, no matter which focal length. The Cooke S5/i looked fantastic at that sweet spot.

Were you shooting RAW on the ALEXA SXT and the URSA Mini Pro 4.6K G2?

Yes. We shot ALEXA SXT 3.4K ARRIRAW, framing 2:1 aspect ratio. On the URSA Mini Pro 4.6K G2, we shot Blackmagic RAW. But it was shot full sensor 4.6K, 2:1 aspect ratio, at 3:1 Constant Bitrate, which is their highest quality encoding. I would say that about 70% of the show is ALEXA SXT and 30% was the URSA Mini Pro 4.6K G2, or the G2 as I would call it.

When did you shoot with which camera?

The ALEXA SXT was for what I’d call our regular, vanilla coverage where we shot the scene as blocked and staged. While the SXT takes were going down, I was observing the action, what the actors were doing, and I made a checklist of the action.

Then, we would shoot what I called our seasoning or condiments pass with the G2. It was for the less conventional coverage because the camera is so small. Essentially, we shot free-form, for want of a better word. It was like visual jazz or improvised operating.

If you do it at the end of the ALEXA SXT takes, when the actors have already expended themselves, they tend to throw it away a little bit more and you can get very loose. Interesting things can happen. We’d run a couple of takes and I would jokingly say to the actors, “I’ll go to whatever’s good. If you’re interesting in this take, I’ll be on you.” I tried to make it a bit competitive with them. They actually started performing to camera. It gives you a very hyper-subjective style of coverage. It’s very effective when you want to try and show if a character’s going through some internal process. It gives you great transparency and insight into what the character’s thinking. There are several charged moments. It’s a great way for the editor to cut to a shot that will give you that energy.

Sometimes I’d stop and start within the take to get 14 different shots in a very short amount of time. They do not look like regular TV coverage. They’re very unconventional shots that you’d never have time to set up specially, but I can find them very quickly in the moment by being able to move the camera around. Because the G2 camera is so small and light, I can use the built-in monitor screen and flip or tilt it up and down and move it around. I can get a huge variety of shots.

When I was in the United States on previous shows, the American crew nicknamed it “the Football” because it’s almost shaped that way and I carry it under my arm as you would carry a football. The actors enjoy doing a “Football” pass because they know that they can play to the camera. It’s a lot like having an audience. They’re aware of where the camera is. The camera operator becomes part of the performance. It’s an interesting way to get unique coverage. What I love is it’s very quick. It doesn’t cost you any extra time and it gives you extra shot variety. Some of the most important shots in the whole show are shot with the G2. The camera is inexpensive but it does produce amazing results.

In short, the idea is to provide overlapping coverage. We would shoot the scene in a regular way with the SXT, and then we’d go back and overlap the coverage with the G2. Then the editor could choose to use it or not. It often works and has great energy about it when you use it. We had no issues inter-cutting. It’s pretty seamless. Most people can’t tell how many and which shots are which.

Can you give us some examples?

Certainly in the episodes I shot (The Beard, War and Vomit, Parachute, Love Hurts and The Beaver’s Nose), most handheld close-ups were probably shot with the “Football” pass using the G2. Many of the very important hero close ups on Elle were shot that way. At the end of Parachute, Episode 6, there is a good example where Peter says, “Science,” and throws the dog off the balcony with a parachute.

It’s actually the last shot of the show and that is a “Football” shot. When the dog and parachute land safely, Elle yells, “The future is bright. Huzzah!”

Huzzah! What lenses did you use with the “Football” G2?

I have some old ZEISS T1.3 Super Speeds, which I like because they’re so physically small.

The matching seems seamless between cameras and lenses.

John Brawley:

I’m amazed as well. There are some scenes that were entirely shot with the “Football” G2. Early in Episode 2, where the Empress is trying to seduce Count Orlo with oysters and she gets sick, almost all of that is shot with the “Football” G2. We had a lot to do that day and it ended up being faster to keep working handheld with quick resets.

How did you light the interior scenes with all those candles?

This was the first HDR show that I have done. I spent a lot of time with our colorist, Paul Staples at Encore in London. He graded with DaVinci Resolve Studio, by the way.

I was trying to work out how to monitor on set. I’m not a big fan of the big DIT tent. And HDR monitoring is tricky in the field because I have not seen small, onboard HDR monitors. There are high brightness monitors, but I find they’re not giving me a true sense of the image precision that you get with the HDR image. One thing I realized quickly was that, although you’re seeing a lot of candles in the show, trying to keep them looking good and looking bright in HDR was actually quite tricky.

I ended up using a top-down approach. I’d use the candle flames to set my base exposure. As long as those candles in shot weren’t clipping, or near clipping, everything else fell into place below that. So, the candle flames had a nice orange glow most of the time as opposed to burning out to white. They still retained subtle skin tones and shadow detail. What’s great about HDR is all the complexity in the mid tones as well.

Did you light with lights or candles?

I knew there would be many candles in shot, so we ended up using a lot of candles as practical lighting. We had double and triple wick candles. I think we went through 100,000 candles over the course of the show, would you believe?

I guess because the UK produces many period shows, I didn’t even have to ask for double and triple wicked candles. The British art department simply presented their choices, “Here are the single wick candles, the double wick candles, and the triple wicks.” I tested them, but they knew from experience that I’d want a mix. We ended up using the doubles most of the time in shot. They were more realistic.

The triple wick candles tended to appear crazy on camera. They looked like you had a giant bonfire going. I saved the triples for off-camera lighting. But they sometimes flickered weirdly.

Production even had a candle stick maker. The lead-time was about eight weeks and we definitely went through a lot of candles. A lot of candle power was going on in these candle-lit sets.

I also used candles even out of shot because some of the characters have glasses and you see the reflections.

Tell us more about the candles that you were using as lighting sources, not in the shot.

We had some film-friendly candles with double and triple wicks that we could place near camera. It felt to me very authentic as a way of lighting. And sometimes I put silver reflectors behind them to project a bit more and increase the light level. An example of where candle reflectors were needed was in one of our location interiors. Four British Heritage people were watching every move we made. We were only allowed to have six candles lit at any one time.

Sometimes we had a few Astera tubes with a candle flame effect cycling on them. But they don’t quite look the same, especially if you look in someone’s eyes and you can see the reflection of the tube’s clean vertical line. It’s much nicer to see candle flames in the reflection.

I also used a lot of tungsten lighting. Most of the show, other than the pilot, from episode 2 to 10, was shot in sets on stage. Although we traveled to Italy for exteriors in Caserta, a giant palace south of Naples, even those interiors were shot on stage at Three Mills, in London. We used a lot of tungsten lighting fixtures because they look so beautiful for skin tones. LED lights are great, but when it comes to skin tones and beauty, I find they can have a kind of pallidness. I generally prefer to use straight tungsten. You might call it vintage or primitive lighting: T12s and 20Ks, and Maxi Brute 9-lights and 12-lights with 1K tungsten bulbs in there.

My favorite LED light is the DMG Lumiere from ROSCO. They’ve got a very good spectral emission, are light weight and versatile. Jean de Montgrand at DMG explained that they have six types of LEDs inside: Red, Lime, Green, Blue, Amber and White. That’s why their color is so nice and I find them to be really good.

Between the candles and tungsten, it felt very old fashioned. Maybe for season two, I should try and drag out some brute arcs and use them as well.

So far, my excellent gaffer Lee Knight has gone with me on my predilection for tungsten over LED and HMI but I’m pretty sure he might draw the line at arcs!

Your lighting was elegant and dramatic. It complemented the story beautifully. It did not look like comedy, or should I say, satire lighting.

Thank you. Traditionally, comedy lighting tends to be brighter and higher key and not as dramatic. Tony didn’t want that. While he didn’t want Game of Thrones dark lighting, he didn’t want it to be tennis court lighting either. We still wanted to treat it like a drama. I had never thought of it as a comedy show. I knew that absurd things happened but it was never written for laughs in terms of slapstick, punch line or rim-shot gags. It was written as drama that has absurd moments of insanity that are funny in retrospect.

But really, we never tried to make it a funny show. Tony is a brilliant writer. There’s a great rhythm. It’s almost Shakespearean.

Tell us more about matching ALEXA with G2.

The looks, colors and dynamic range of both cameras were quite similar. They matched very easily, with not much tweaking required. In pre-production, we worked up a whole lot of tests to create the look of the show with the showrunner and the producers. We talked about what it should look like and we distilled that into a look, as embodied by a LUT. There is a daytime version and a night version of that look.

Then we made a LUT for each camera: one for the ALEXA and another for the G2 so they both matched. When it went into the edit, everything looked seamless.

Certainly there were visual differences because of the way the cameras were operated: one was handheld and the other usually was not. In the final grading, we tried as much as possible to match to the dailies. We got very close in the final grade, and usually I could only tell by looking at the style of shot it was. Sometimes you could see slight differences in resolution, but that was the only difference.

Filters on the lens?

I used some very light Schneider Black Frost filters, 1/8 and ¼ depending on focal length. This minimal amount of diffusion on both cameras was just to take a little bit of the edge off. As you know, Elle is amazing, she used barely any makeup, which again was a very brave choice that she made. Most of the cast also had very little makeup. Of course, they have big wigs and hair pieces.

Were you viewing on set with HDR monitors?

At one point, we looked into getting some consumer HDR televisions and turn those into a village. But it seemed clumsy and not very agile. In the end, the village didn’t need to watch in HDR. It felt like shooting film.

The on-set monitor was like the workprint. You understood what it would look like in the final grade as long as you were careful in terms of exposure. You didn’t have to see it in dailies to understand that it would be transformed and more beautiful than what you saw on set, because that was the process. I didn’t fret about it. I knew that as long as I didn’t over-expose, I was pretty safe. As mentioned earlier, I was often exposing to the candle flame illumination levels. With HDR, I tended to protect the highlights more, letting everything else fall below that, and trusting that the dynamic range of the camera, whether ALEXA or G2, would be able to lift those areas back up. And they did. I thought it worked well as an approach.

- John Brawley with “Footbal.” Photo: Andrea Pirrello © Hulu

- L-R: Writer/Producer Tony McNamara; and DP John Brawley. Photo: Andrea Pirrello © Hulu

Did you operate yourself?

Usually only the “Football” shots with the G2. We had two wonderful operators, Jessica Clarke-Nash as our B-camera Operator, and James Layton on A-camera and Steadicam. So, I would sometimes come in at the end with the G2, but only because it’s very improvisational and driven by performance, with the cues and timing coming off the actors. The other operators could do it but it was something I enjoyed doing myself to dip my hand in it, so to speak.

I was using the built-in monitor of the G2 camera. That’s what mades it so cool, because the camera’s really tiny and, like a Handy cam, you can hold the camera with one hand. It’s light enough that, for example, I could look straight down on a table and if I held the monitor with the other hand, I could pivot the camera and look straight up. That could happen in shot, which was a very flexible way of shooting.

If you add in the fact that I could swing my arms around, or crouch down low and then hold it high above my head, you got a lot of shot and lensing variety by being able to move around so freely. The camera is not stuck on your shoulder. That is why this style of coverage was kind of unique.

I vaguely remember you were born in New York.

The backstory is my mum was a hippy. She was in New York in the late ’60s and the early ’70s, and went to Woodstock. I was of product of that era and I was born there. Then my mum ended up going back to New Zealand when I was about 12 months old, so I grew up in New Zealand until I was about five, and then we moved to Australia after that. So, I identify as Australian but technically I’m an American.

A child of Woodstock. Far out.

Haha, definitely she would say that. I’ve got great pictures of my mum sitting in trees at Woodstock and hanging out. She was the real deal.

And how did you get into film?

Photography was always something that was very interesting to me as a kid growing up. It was the first hobby I found where I didn’t get bored because it was a great way to combine other interests as well.

I started doing photography when I was very young, I had a great art teacher in primary school. He taught me to take stills, how to print and process black and white film.

I grew up mostly in Melbourne. I did a lot of photography when I was a kid and I loved what a camera could do. At that time, the first Gulf War was happening. There were a lot of protests and I could use my camera to get access. I was also doing live music photography. I was in pubs, shooting bands. I was underage. I wasn’t even meant to be in there because I was 15 years old, taking photos of bands late at night and during the day when I was supposed to be at school. Half the time, the bands were my music teachers.

At university, I started in media and photography. But, it had a cinematography component and I was hooked at that point. I shot some film on an ARRI ST and became addicted to the moving image at that point. So, that’s where it began.

Cinematography is a great combination of science and technical knowledge in the service of a creative outcomes. It is endlessly fascinating to me and continues to give me great joy.

This has been a fascinating talk. Great work. Huzzah.

Huzzah. That’s right. We were all hoping that we’d get some vodka glasses at the wrap party so we could smash them and all say, “Huzzah.”

Paul Staples on Grading The Great

Paul Staples, colorist at Encore in London, comments:

John and I worked on setting LUTs during prep. I loaded the ARRI and G2 Raw test files into a DaVinci Colour Managed project, took stills, then repeated the process into a non DaVinci Colour Managed project timeline and matched them to the DaVinci Colour Managed project stills. The show project was UHD Dolby Vision HDR P3 at 23.98 fps.

We used DaVinci Colour Managed colour science which is within the DaVinci Resolve Studio software. I then produced LUTs for both cameras that would be used on set and in editorial. When it came to the grade, we worked in a DaVinci Colour Managed project and I pasted a saved correction node which contained all the parameters to match. This worked extremely well, and brought the two cameras within a hair’s breadth, giving me continuity across the timeline. With the help of DaVinci Resolve Studio’s collaboration mode, this could be looked after in pre-grade, which really helped as the shows had a very tight turnaround schedule.

In the grade, we used a pared-down HDR show LUT. This was only a base to get continuity across the timeline. I wanted maximum flexibility to bring the nuances of the work out and not suffocate it with a heavy aggressive look straight out the box, and also to still maintain a look continuity conducive to the showrunner’s brief and, of course, the look that series DP John Brawley sought.

(This is a “reprint” from August 2020 FDTimes issue 104.)