- Dan Sasaki testing a lens at Panavision Woodland Hills.

- Panavision team in front of Lens Bar at 2018 Cine Gear. Michael Cioni is third from right in the front row.

Dan Sasaki, VP of Optical Engineering at Panavision, and Michael Cioni, Senior VP of Innovation at Panavision and Light Iron, have a few things to say about Large Format.

JON FAUER: Let’s begin by talking about a fun subject, lenses and wine, and how they relate.

MICHAEL CIONI: I’ve always felt that comparing lenses is a little like tasting wine. If you’ve ever done a wine tasting, you know that unless you have a direct comparison, it can be difficult to truly discern the notable, even subtle differences. Our biological reset mechanism prevails and as soon as you switch drinks (or lenses), you may forget some of the details of what you were observing even moments ago. Have you ever gone skiing or snowboarding and noticed that when wearing orange goggles the snow eventually appears white? That’s an example of how good our brain is at neutralizing and resetting. I think what I’ve noticed in a lot of lens evaluations is that the reset function in each of our brains can make the most critical differences difficult to observe.

JON: Good point. When you do a wine tasting, there are often four or five glasses in front of you and you compare them. Most lens tests have been shown with one lens after the other.

MICHAEL: At the BSC Expo in London, we had a lens bar of Panavision optics and our new lens demo screening system. Like a wine tasting, it’s helpful to compare them together and at the same time.

So, when we shot our latest lens tests we came up with the idea to use a click track so the actors could repeat the same action over and over while shooting with each lens from the same camera, same vantage point and same focal length. We then play back the footage on four 4K monitors simultaneously so DPs can make the comparisons at the same time. We’ve all seen lens tests conducted with various lenses on multiple cameras, but the problem with that is each angle is different because of the parallax. So, our idea was to shoot everything from one camera position, change the lens, and repeat the action for the best evaluation experience.

The Panavision Lens Bar at this year’s BSC Expo was bigger and became more hands-on. It’s sort of like a lens petting zoo. We’re not championing one set of lenses. We offer a variety of lenses and let the Cinematographer decide which fits their project which makes the experience very personal. In terms of large format, when the Panavision Millennium DXL 8K camera was introduced in June 2016, how many lenses did we have?

DAN SASAKI: Now we have 11 series of large format lenses.

- Panavision Ultra Vista lens tests. Michael Cioni at camera.

- Kylie Hazzard mounting a PanaSpeed on DXL2 for testing.

11 Series of Panavision Large Format Lenses

Sasaki, Cioni and Panavision Large Format, cont’d

- Shooting the Panavision quad-split lens tests

Cinematographer Brandon Trost and Director Marielle Heller on location in the Logos Bookstore (coincidentally across the street from FDT in NYC). Photo: Mary Cybulski.

JON: Thinking of our wine analogy, “vintage lenses” like “vintage wines” were not considered “vintage” when they first came out. Hopefully, they were the best that a manufacturer could build. When Panavision first started making lenses, were cinematographers using the vocabulary of character and look that we discuss today? I have a feeling that lens choice back then was more a matter of whether the lens was “good” or not. Am I wrong about that?

DAN: That is correct. Many of the characteristics cinematographers tried to avoid in the past are now attributes. I believe this is largely due to the many outlets where an audience can view material. We are viewing shows on smaller devices such as televisions and personal devices as much as large theater screens. The visual cues stimulated by home viewing differ from those being used when viewing a movie at a large screen venue. Many of the nuances we might have ignored or avoided in the past are becoming more relevant and interesting. Due to this, the paradigm of how we choose and create lenses has changed quite a bit.

JON: Dan, has your job therefore changed over the years? In the film era, were you trying to overcome the bouncing film in the gate and the projector and the multiple generations from negative to print degrading the image? But now it’s another story: we are much more aware of different looks, different feels, different styles?

DAN: Yes, you summarized it well. In the last two years, I have seen more changes to lens imaging traits than I have over my entire time at Panavision. The changes in cinematography trends have made it possible for a new lens class to be introduced at nearly all of the major trade shows such as the BSC Expo.

MICHAEL: The Lens Bar is also a bidirectional place where we get feedback from users and it helps us modify or augment what we’re doing based on that. We have had a number of lenses change in prescriptions based on user feedback. Sometimes we expect a lens to behave or be used in a certain way when it’s actually used in a different way. For example, last year, Dan built one Ultra Vista lens and people had a strong positive reaction to it, so that encouraged us to build many more.

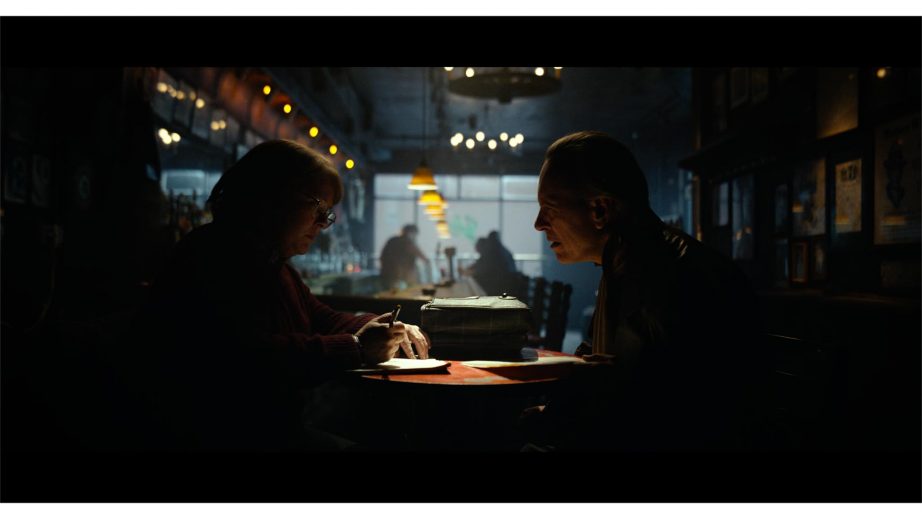

One of the favorite lens series for the DXL has been the Primo Artiste. The first person to use the Artiste on DXL was Brandon Trost on the film Can You Ever Forgive Me. Brandon worked with Dan on optimizing and finding the ideal prescription that looked best for the show. Since then, a lot of people have elected to use Artistes after seeing the results from that first shoot.

Cinematographer Brandon Trost commented: “Often, large format is chosen for grand scale and scope. Can You Ever Forgive Mewas the opposite. This system can really allow for a special sense of intimacy and closeness. We wanted to feel like we were in the rooms right next to our characters, experiencing this story with them. The large sensor helped us with a more personal feeling of depth. I chose to shoot DXL at 3200 ISO because I loved the texture and subtle softness that it induced while allowing for low light levels. The Primo Artiste T1.8 lenses told the story perfectly. The shallow depth of field and smooth optical resolution allowed for the sense of time and intimacy we wanted to feel.”

JON: What specifically was done to create the look of the Primo Artiste lenses?

Can You Ever Forgive Me? Panavision Primo Artiste lenses. Light Iron Colorist: Steven Bodner. Frames courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Can You Ever Forgive Me? Panavision Primo Artiste lenses. Light Iron Colorist: Steven Bodner. Frames courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures.

DAN: Basically, we started with a look in mind and came up with a new design that was amicable to the aesthetic we were after. Once the core design was decided upon, we targeted a handful of aberrations. Think of those aberrations as ingredients in making a cake. The proportions of those aberrations give the cake a unique flavor. Without getting in too deep, we enhanced certain ingredients to be stronger than others. It comes down to what Michael said: we have a very short-term memory for what our eyes process. Because we really don’t see with our eyes. We see with our brain. And our brain is constantly trying to match and make sense of things. Realistically, any casual variances or types of qualities that stand out are what give the Artiste lenses their style.

With the Artiste lenses, you’ll notice the contrast looks different from a modern lens. In the digital world, automatically you’re going to see a lot more contrast, so we had to break that down. Oddly enough, a lot of the artifacts that we targeted in the Artiste lenses were preferred to be corrected and avoided in the 70s because we were working with motion picture film emulsions. For example, the flares and color attributes that were the result of the anti-halation layer on the film was disturbing back then. But now, we find that people gravitate towards that kind of glowing flare.

I believe this type of artifact is more sought after these days because it provides a characteristic. It’s something that survives imaging chains and preserves a unique character that identifies a cinematographer’s artistic intent. It really comes down to the unique combination of ingredients that go into the Artiste. Basically, select aberrations and the proportions of those aberrations are what we use to give the Primo Artiste lenses their unique look.

MICHAEL: There’s a lot of debate out there surrounding perceived benefits of shooting large format. Brandon celebrated the use of large format on Can You Ever Forgive Me. He often favored wider focal lengths, got closer to the subject, and shot wide open. Even when he was shooting in daylight, he put on ND filters so he could maintain a T1.8 aperture.

The Artistes have a unique contrast characteristic where they will give you good focus and rich blacks, with a hint of light wrap.

“This new class of large format sensors has made it possible for anamorphic to have a technical as well as an artistic advantage over its spherical equivalent in the digital arena.”

That light wrap “takes the edge off.” I’ve seen situations where the halation, which is one of your five major lens characteristics, actually acts a bit like a fill light. If you are keying someone from the left side, the halation wraps the light around and it fills in the shadow side slightly. There are a few examples of that in Brandon’s film, because he used a lot of New York natural lighting situations in the film.

JON: It was a painterly look, golden in the highlights. If we were comparing wines, it would probably be a Chateau Margaux 2005. I hope you pour that at the lens bar. It was elegantly rounded and gorgeous. Next, can you please tell us more about the Panavision Ultra Vista lenses?

Above: 4K framegrab from Panavision Ultra Vista lens test, with model Aubrey Cooke. Available light with DXL2. Light Iron Color2 Film LUT with no additional correction.

MICHAEL: The Ultra Vistas are full format anamorphics with a 1.65x squeeze. They’re built from scratch. The focal lengths right now are currently 40, 50, 60, 75, 100, 135, 150, 180 mm and we’re working on zooms at the moment.

JON: How did you settle on the 1.65x squeeze?

DAN: The 1.65x squeeze came about as the result of a squeeze progression ratio. There were multiple considerations involved. The ARRI LF and Sony VENICE have approximately a 1.5:1 full format sensor. The Panavision DXL and RED Monstro 8K (and Canon C700 FF) have a 1.9:1 full format sensor. With all these sensor sizes, 1.65x retains as much of the native resolution as possible while maintaining the anamorphic look of 2x. Largely, it worked out this way because we don’t use spherical components to correct the focus. We use cylindrical correction to accommodate focus and as a result the lens tends to maintain a more anamorphic look. Another reason we targeted the 1.65x squeeze is due to something called the Renard Series (a system of preferred numbers). We considered the squeeze ratios of the various anamorphic lenses Panavision offers. These are Ultra Panatar with 1.3x squeeze, Ultra Vista with 1.65x anamorphic squeeze, and traditional 2x squeeze anamorphics. The Renard Series points to a 1.2x progression from one format/aspect ratio to the next. This progression translates into a series of anamorphic lenses that have their own unique characteristic and identity. Each series does not walk over each other and there are certain technical attributes that uniquely separate one lens series from the other.

We also are noticing that aspect ratios are fluid lately. More OTT streaming shows are requiring 4K distribution. With the 1.65x squeeze, we can give someone a 1.76:1 aspect ratio and still maintain 4K. A good example would be the current series Homecoming which switches back and forth from 1:1 square aspect ratio to 1.76:1 (16:9) throughout show. I’m noticing that more and more.

Another example is Marvel using the 1.9:1 aspect ratio as its base delivery format. It is worth noting that anamorphic does not necessarily mean a 2.40:1 aspect ratio anymore. Anamorphic lens technology has many valuable attributes that give a cinematographer the power to negotiate through various aspect ratios with maximum fidelity. This new class of large format sensors has made it possible for anamorphic to have a technical as well as an artistic advantage over its spherical equivalent in the digital arena.

MICHAEL: The Ultra Vista lenses are a cool twist of arithmetic and in a league of their own. If you use the 1.77:1 area within the 1.9:1 sensor of DXL2, and then shoot with 1.65x squeeze anamorphic Ultra Vista lenses, you get a 2.76:1 desqueezed aspect ratio. You can use 92% of the entire sensor, and are able to distribute in Ultra Panavision 2.76:1 format at 7.5K. Furthermore, you’re getting another 60% magnification factor because of the large format anamorphic. So, the big sensor and the big resolution and the big squeeze all add up to something completely different.

And it’s an optical characteristic people really notice. Every time we show a demo of all our lenses, when they see the Ultra Vistas, they ask, “What’s that?” There’s something about them that stands on their own that’s probably the combination of all the things we talked about.

JON: How would you explain the differences technically, and also in look, between the Ultra Vistas and Ultra Panatars?

DAN: The primary trait of the Ultra Panatar lenses is they have a 1.3x anamorphic squeeze and basically use the entire large format sensor area or motion picture film aperture. Although they possess a weaker anamorphic squeeze, they still provide the visual attributes that are anamorphic. The Ultra Panatars still produce the anamorphic lens flares, the unique vertical breathing, and convolved out-of-focus bokehs.

The focus decomposition (the unique quality that an anamorphic lens de-focuses versus a spherical lens) is less than that of the Ultra Vistas. This means that the disproportionate focus fall-off of the Ultra Panatars is not as abrupt and significant as the falloff associated with the Ultra Vista lenses. For example, the elliptical out of focus cues are not as exaggerated. The depth of field of the Ultra Panatars appears to have a less full anamorphic characteristic, yet the qualities of the image definitely do not look spherical. The Ultra Vistas, on the other hand, have a 1.65x anamorphic squeeze which is about 1.2 times more squeeze than the Ultra Panatars. Ultra Vista anamorphic lenses yield more deliberate anamorphic out-of-focus and depth cues than the Ultra Panatar optics.

Now if you apply that mathematically to the DXL, for the first time since digital cinematography came about, anamorphic now has a technical advantage over its spherical counterparts as well as an artistic distinction.

This is the result of the multiplication factor of Ultra Vistas when it is leveraged with the high magnification and the sheer amount of pixels associated with larger format sensors. Ultra Vistas have a compression (magnification) factor that is about 2.5 times more than their native spherical Super35mm counterpart. So, if I’m doing my master wide shot on a 27mm lens in the Super35 format, compare that to the DXL large format where I’d be using a 67mm Ultra Vista lens to get the same field of view. It’s kind of crazy when you think about it.

Considering magnification and out of focus cues, Ultra Vistas are a 1.2x greater step up from the Ultra Panatar lenses. You are going to share the familiar attributes of the anamorphic flares, the vertical breathing, but with a higher intensity.

The next step in the series (Renard) would be 2x squeeze anamorphic optics, which would be the next mathematical step in the progression. A casual viewer may not see the differences independently. But as Michael said, if you see them in relationship to each other during a demo test, those differences will actually stand out on small television sets or monitors. Each series has incrementally different amounts of anamorphic feel and personality built into them that are familial yet possess their own characteristic that is unique to their brand.

MICHAEL: At this point, it’s worth talking about what happens when the content ends up on a Smartphone. I often hear cinematographers, content owners, directors and producers having concern that it’s not worth shooting large format because you can’t notice the benefits when it gets to the phone. But the fact is, that’s not an accurate assessment of how display pipelines work. The most important thing about this entire subjects is that all the optical properties we’ve discussed here are resolution independent.

Virtually the only thing you can’t see on a phone is how many stitches are in the blanket in the shot. That is pure resolution, which admittedly very few people are after. But magnification, field of view, depth of field, distortion, physical distance between subject to lens and subject to background, all of those are relevant at any scale and at any resolution. Glare, spherical aberration and color, of course, all translate to any resolution at any scale. Sometimes people think it’s not worth spending the extra dollar for the good stuff, but honestly it all translates and it makes a difference. I think what Dan’s doing with his team is taking lenses to the next level and DXL takes cameras to the next level and all of these qualities can even be experienced on a phone.

“aggregate aberration accumulation”

We have to work harder to make sure that our unique characteristics translate. That’s why we talk about 8K from its magnification properties and detailed clarity properties, not in its resolution or sharpness. I don’t think you’ll find a quote anywhere of me talking about sharpness as an advantage. I talk about 8K and large format as workflow and creative tools. And, partnering optically with the Ultra Vistas, these are among the best examples of what all of these things together can achieve.

JON: Earlier, you mentioned the five lens characteristics that contribute to the look. What are they?

DAN: I guess for lack of a better word, we call them the “five tenets” that viewers tend to see. You don’t have to have a technical degree in optical physics. These are all unique characteristics that you can recognize regardless whether you’re watching on a 50-foot screen or a 4-inch smartphone. Flare, glare, bokeh, spherical aberrationand colorare the things that will separate brand A from brand B in an optics/camera/post-production combination. Let’s not forget that post has a large provenance in the overall look. If I were to take a picture and add a sepia tone to it, we instinctively tend to think of it as antique, something from the past. Color has a very big influence. We don’t want to define look strictly by the lens only. It’s an entire infrastructure of the whole imaging chain.

MICHAEL: I would also add also add magnification factor, because when you use large format and you get a different geometric relationship between subject, camera and background, that geometrically translates as well to the phone.

JON: Dan, as Panavision’s “lens sommelier,” what are the 10 different varieties of lenses that you are “pouring” at the BSC Expo Panavision Lens Bar?

DAN: Well, to continue your wine vocabulary, perhaps a Pinot-like Primo 70, or a well-rounded Ultra Vista. The System 65 comes from an excellent year, as do the Sphero 65, the H Series, the Ultra Panatars and the Artiste lenses. We have the new, expanded 2x squeeze anamorphics that cover full height of the 5:4 full format sensors. There are modified PanaSpeeds, and something else I think we might introduce at BSC—we call them the Vintage 65 Spherical lenses.

JON: What are the 2x anamorphic full height lenses that you just mentioned?

DAN : Our 2x squeeze anamorphic lenses for Super35 were traditionally based on the Academy aperture or sensor height, which is about 18mm. Now, with the new class of sensors, the image height ranges from 20mm to 25mm high. So, we had to redesign our anamorphic lenses to cover up to 25mm height. Basically, it’s a redesign or a re-spin of our existing 2x squeeze anamorphic inventory to cover the full height typical of the full format cameras like the LF, VENICE or the DXL.

JON: Do you have to build these lenses from the ground up?

DAN: In most cases, we actually take the existing lenses and modify them. We’ve modified the optics, rescaled the focus and rebranded the lenses to reflect their new iteration.. It was kind of a partial redesign, but it wasn’t from the ground up. And we are always working on additional new lenses.

JON: I noticed that you also carry Tokina Vista Primes as well?

DAN: We like Tokina’s design philosophy and we started renting them. They chose a fairly traditional design form that utilizes a type of free form design to reduce the aggregate aberration accumulation. I liked the Tokinas because they based a lot of their design philosophy around known tenets that offer very strong artistic qualities without being too crazy. I think Dr. Aurelian Dodoc of Leitz Cine said a similar thing: it’s relatively easy to make a technically perfect lens. It becomes very difficult to make a lens that provides an artistic look because you’re actually making an imperfect lens that has an attractive appeal to it.

JON: Do the Tokinas retain their native PL mount or do you rework them with an SP70 lens mount for the DXL2 camera?

MICHAEL: Right now, all of our Tokina Vista Primes are out on jobs. We’re using them with their PL mounts. There might be a possibility that we fit them with SP70 mounts later on. But we already have the SP70-to-PL mount adaptor that’s very easy for customers to use. They can shoot with the Tokinas and Primo 70s on the same job. That’s another change in cinematography recently. DPs are switching lens series within the same job a lot more than they ever used to. When Dan and the engineering team came up with the SP70 mount and adapters for the PV, PL, and other lenses, it became incredibly handy. We used to have to change the physical mount on the camera every time we changed a physical mount on the lens. Now it’s just a mechanical adapter. I think that is another example of DPs looking for their own recipes. I’m proud to have these new Tokina Vista Primes working on the DXL2. These lenses are a good example of how the cinema lens market is widening with new contributors, and you know I believe that change is super healthy. It is an indication of how fast the large format market is exploding. That’s another healthy change to our market.

JON: Do users mostly prefer to have the SP70-to-PL adapter on the camera, or do they prefer to have an adapter on each lens?

MICHAEL: Usually on the camera—so you need fewer adapters.

JON: Dan, I remember when we were talking this time last year and making grand predictions about where the business was going and where you saw full format compared to Super35. How has that changed this year?

DAN: We’re seeing more and more traction of full frame format. But what’s interesting, and I really didn’t see it coming, was the domination of demand for full frame anamorphic.

I think it has a lot to do with the fact that anamorphic has such a unique look. For example, if I put any of the well-corrected spherical lenses on a digital camera, they would pretty much start looking the same. Many spherical lenses from 1980 to present, whether Master Primes, Super Speeds, Primos, or Primo 70s, have compression artifacts that look similar. If I do the same exercise with an anamorphic lens, the qualities associated with out-of-focus bokeh, flare, glare, and color are uniquely different. As a result, I am noticing a lot of cinematographers are gravitating towards full frame anamorphic.

I have observed many cinematographers like the fact that the unique magnification of large format really sends a message, and this process is even more prevalent with large format anamorphic. This trend is beginning to dominate the way movies are shot and viewed. I had underestimated the power of anamorphic and its relevance in full frame cinematography. I figured that the magnification changes associated with full format spherical, by themselves, would have driven the direction of large format cinematography. Instead, I’m seeing a shift where large format, coupled to a variation in anamorphic optics, manipulates the five tenets in a very unique manner and is becoming a very popular choice among cinematographers.

Within the last one to two years, the proliferation of spherical full frame has most definitely grown, but it’s almost become commoditized. The anamorphic proliferation has increased exponentially. We’re seeing a rebirth of anamorphic photography and cinematography, something similar to the 1970s when there were more than 80 different varieties of anamorphic lens manufacturers or processes.

Tak Miyagishima made a list of all the different types of anamorphics that were available, including all the CinemaScope derivatives: from Adhi Scope to Yangtze Scope, with Superscope, Panascope, Pariscope, Technovision, Todd-AO and Toho-Vision along the way. You can see more than 200 variants by googling and going to the glossary of Gary Palmer’s Widescreen List.

MICHAEL: That’s when anamorphic was used to overcome the grain and limitations of 35mm film at a lower cost than 65mm film.

DAN: Michael brings up a good point: anamorphic had a distinct technical and financial advantage, but then it slowly died out through attrition. Lately, I’ve noticed how anamorphic is gaining ground again, not only because of its technical attributes, but mostly for its artistic qualities and its unique imaging characteristics. Couple anamorphic with large format, and for the first time since digital sensors came out, anamorphic again has a technical advantage over its spherical counterparts. There’s no right or wrong way to make anamorphic lenses. The net result comes down to really cool artifacts that cinematographers seem to grab onto and really take notice.

MICHAEL CIONI: Something I noticed in the last year that also changed was the question about resolution. It’s no longer a taboo subject. I think it shows the market maturity and understanding. 2018 was a year where everybody has gotten onboard 4K and higher, and we’re all headed in the same direction. Even in the consumer electronics market, you can’t even buy an HD TV anymore if you wanted to.

4K carries very well to smaller monitors. HBO, Netflix, Amazon, and other entities have embraced anamorphic. Originally, you couldn’t shoot anamorphic for episodic unless you got specific permission, or the most you could go was 2:1 aspect ratio. Now that’s changed, and I think we have the mobile platforms to thank for opening up those floodgates.

JON: Back at the Panavision Lens Bar and Lens Test area at the BSC Expo, what else can we expect?

MICHAEL CIONI: This year’s Lens Bar is the first time we show tests simultaneously on four 55-inch 4K monitors. It’s a video wall that compares 4 lenses, one on each monitor. Our hope is that users take a moment to watch the lens tests and then go to the Lens Bar and discuss their own “wine pairings,” recipes or mixology. All our lenses are represented at the Lens Bar, so users can test, hold, inspect and ask questions. Panavision lens experts are there to answer specific questions.

We are also showing improvements to our recent /i lens metadata adoption and other things that help improve the lens on the workflow side of things. The DXL did not support /i a year ago, but now it does. At Panavision, we are very focused on the entire imaging chain. And so much of it starts with lenses.

Reprinted from Film and Digital Times February 2019 Edition #92