This is the lead story in the September Edition of Film and Digital Times–coming September 9.

La Cinémathèque française in Paris will exhibit “From Méliès to 3D: the Machines of Cinema” from Oct 5, 2016 – Jan 29, 2017.

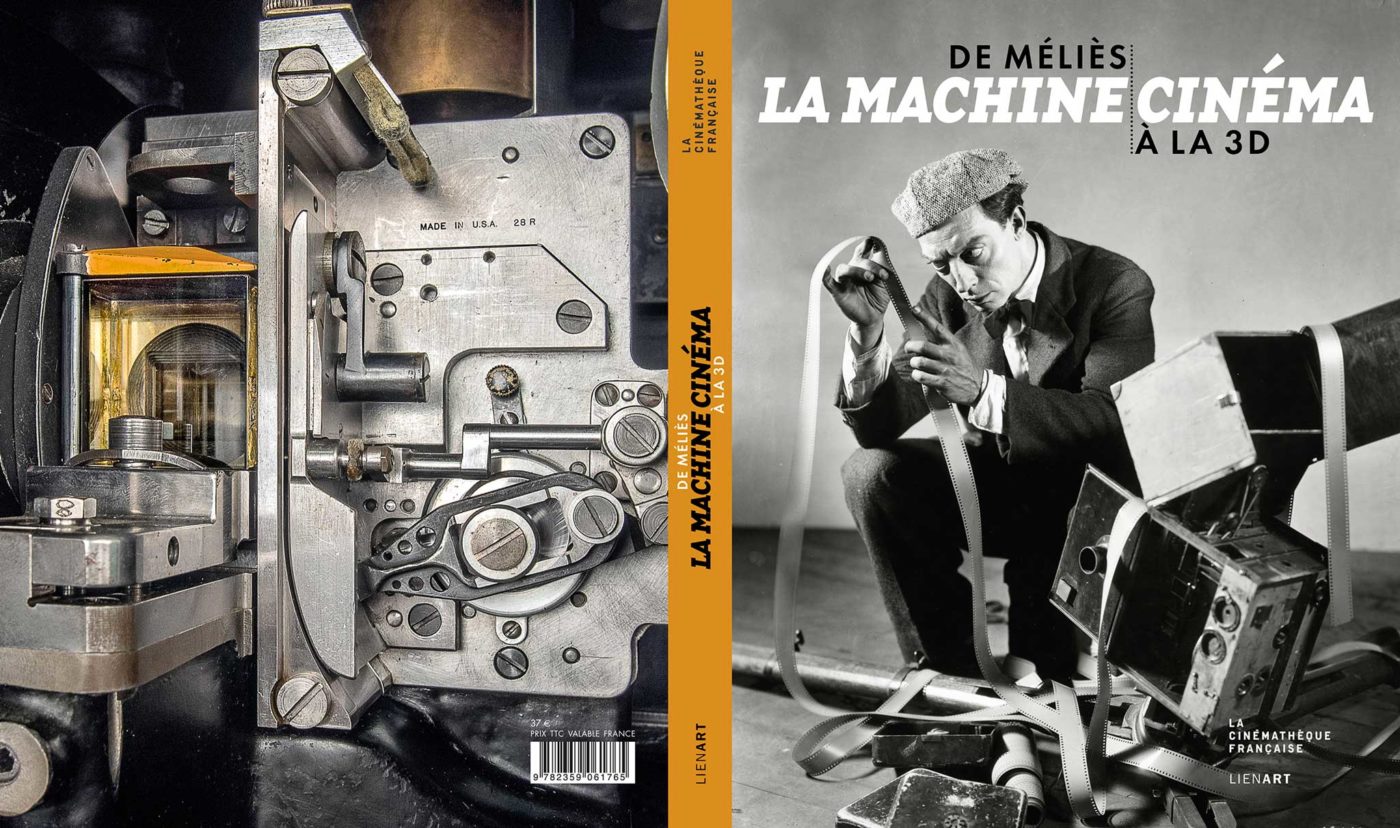

Laurent Mannoni, Director and Conservator of the Cinematheque, curated the exhibition and wrote the wonderfully informative accompanying book. (Coedition Lienart / The French Cinematheque. 304 pages, 350 illustrations, October 2016.) Laurent looks after the Cinematheque’s vast collection, by far the best in the world, in an annex normally open by invitation only.

Now the Cinematheque puts on display more than 250 historically significant “machines” (total of 12 tons) that made moving pictures. Laurent writes, “This book is intended as a path in the long history of cinematic techniques through the collections of the French Cinematheque and through some 120 dates (from the eighteenth century to the present). We see each important milestone. It shows the almost Darwinian progress of filmmaking.

“The challenge of this work, as well as the accompanying exhibition, is to remember that the cinema is a highly technical art, much more than all the other arts. We want to understand how technology creates new forms, and conversely, how the desire to create original images gives birth to new devices, systems or processes. Cinema is born from the union of science and invention, continuously improved thereafter through the combined efforts of artists, technicians, physicists, opticians, chemists, biomechanics, and computer.”

The waypoints of this exhibition follow the birth of cinema (late 19th century), Talkies (1927), Technicolor (1932), CinemaScope (1953), Large Format 70 mm (1955), the New Wave (1950), to the present. The exhibition has unique equipment on display: the first cameras used by Marey, Lumière and Méliès, the classic Technicolor cameras of Hollywood, Jean-Luc Godard’s handheld 35 mm 8/35 Aaton, and the underwater housing from Oceans.

Many of our familiar friends are here: an Angenieux – Franscope anamorphic zoom lens (1958), the Louma (1970) from Jean-Marie Lavalou and Alain Masseron, Garrett Brown’s Steadicam (1974), ARRI’s 35BL from Raging Bull (1980), a Super Panavision Silent Reflex camera (1983) and Platinum handheld (1986), Jacques Delacoux’s first Transvideo monitors (1985), Howard Preston’s Light Ranger (1990) — a giant ancestor of his latest, graceful LR2 that guides distance measurements and enables autofocus.

Le Cinéma Numérique begins for Laurent in 1995 with Danish Dogma films and Anthony Dod Mantle’s work with Sony prosumer DV cameras that awed critics at Cannes. Lucas follows with a Sony F900 on Star Wars II (2002), Panavision with their Genesis CCD camera (2005), RED One in 2007 and Stephen Soderbergh’s RED Epic on Che (2008).

The digital doyennes are here: ARRI’s Alexa (2010) and Aaton’s Penelope Delta (2012). Laurent is not a fusty academic pining for the long-lost days of Cinéma Argentique. He writes, “The choice of equipment is crucial for a film. Orson Welles and Gregg Toland used one of the first non-bulky, quiet cameras—Mitchell BNC— on Citizen Kane (1941). On Body and Soul (1947), James Wong Howe, wearing roller skates, performed virtuoso moves for a boxing match, using the small 35mm Bell & Howell Eyemo, with its spring motor typically used by war reporters. Final aesthetic deeply depends on the choice of tools.

“Each filmmaker has a different relationship with the technique, and it’s fascinating to study. If the New Wave revolutionized cinema, thanks to inventive cinematographers like Raoul Coutard, it also benefited from a new generation of lighter handheld cameras and technology.” The new wave crossed the Atlantic. Like a moth circling a flame, Haskell Wexler captured the searing drama of Virginia Woolf hand-holding an Eclair CM3.

“Digital technology offers the cinema incredible results. However, some filmmakers do not agree. They prefer the vibration of silver grains to static pixels. It is true that digital is subject to rapid obsolescence. Try to operate today the first professional digital cameras, or the first digital projectors that appeared in France in the late 1990s. The software has disappeared, components are no longer made, the computer stops responding.

“On the other hand, a Lumière Cinématographe from 1895, with its old mechanism, its claws, its ribbons of film, still works today. All one has to do is simply turn on the lamp, turn the crank, and images magically dance upon the white wall in a darkened room. This is perhaps the most beautiful lesson we learned from Louis Lumière: the timeless power of cinematography and the memorable legacy of the Cinématographe confront the virtuality and volatility of digital.

“Let us trust in the future. Cinema offers an eclectic mixture of technology and artistic sensibility that often allows the production of major and surprising works. Digital, even with its volatility and propensity to devour everything, opens up exciting prospects. What matters is that the cinema, the writing of movement, born in prehistoric caves, remains very much alive as an art today. The cinema, as Abel Gance said, must always be reinvented.”

(Translated from Laurent’s French manuscript by Jon Fauer. I hope I did it justice.)