Peter Suschitzky, ASC will be honored at the Cannes Film Festival on Friday, May 20 with the Pierre Angénieux “Excellens” in Cinematography Award. He will conduct a master class on Saturday, May 21, at 11 am in the Radisson Blu Hotel, Salon Marius (2 Boulevard Jean Hibert – Cannes). The session will be sponsored by Thales Angénieux, with limited seating to those holding Cannes Film Festival accreditations.

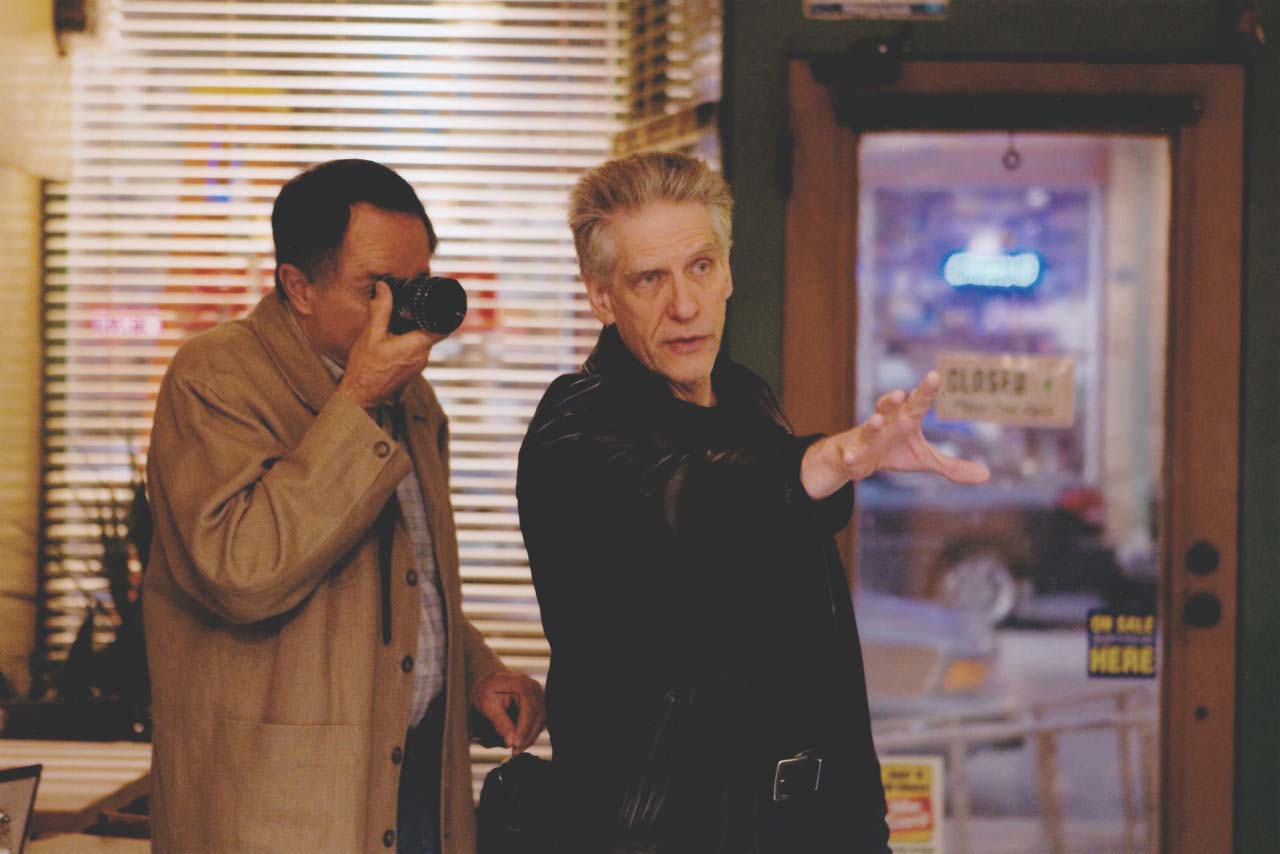

Peter Suschitzky was born in London in 1941. He is the son of renowned cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, who is now 103 years old. Peter was the cinematographer on more than 50 films, including most of David Cronenberg’s films since 1988: Naked Lunch (1992), Crash (1996), eXistenZ (1999), Spider (2001), A History of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), A Dangerous Method (2011), Cosmopolis (2012), and Maps to the Stars (2014).

We spoke a few days ago:

JON FAUER

Let’s begin by talking about the Pierre Angenieux Award that you’re receiving at Cannes.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It’s the fourth year that they will be giving an award to a cinematographer and they chose me. I don’t know how it happened, exactly. But it’s very flattering and exciting.

JON FAUER

Congratulations.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It’s a lucky season for me because I just got the Italian film academy award, the “David di Donatello,” for my work on “Tale of Tales” which has just opened in the States.

JON FAUER

Please tell us about that film.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It is one of a kind. It’s unlike any other film out there. It’s taken from a series of folk tales that were collected in 18th century Naples. I think it was the first collection of fables published and it came to the attention of the Brothers Grimm some 50 years later. It’s a conflation of several stories, with princesses, a king, a queen and a dragon: all the right elements for a folk tale.

JON FAUER

Where did you shoot it?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

We shot in many locations in Italy: Sicily and Puglia in the south, central Italy, Rome, Lazio and Tuscany. We went to some very beautiful, out of the way places.

JON FAUER

What equipment did you use?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It was a rather difficult film for me because it was 100 percent Steadicam, the first time for me that an entire film was shot this way. We used an ARRI Alexa camera.

JON FAUER

Who was your Steadicam operator?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

We had a wonderful Steadicam operator, one of the very best in Europe: Alessandro Brambilla. Not only is he a very nice person, but his camera moves are so smooth and steady, they almost look as if he was working on a dolly. When called upon to do a fixed shot from the Steadicam, he was rock steady.

JON FAUER

What did you use for lenses?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I chose to work with Panavision Primos.

JON FAUER

I assume you used Angenieux zooms as well?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Almost all the shots were done using prime lenses but we carried a zoom with us, an Angénieux by the way, and we must have used it on two shots. On “After Earth” we used zooms a lot, particularly when the camera was on a crane, because that always gives greater flexibility. Whenever I think of a zoom I tend to automatically think Angénieux because they are amongst the best that you can find.

I do, however, like the discipline which necessarily comes with the use of a prime lens and I have, with David Cronenberg, often used only one focal length lens for all shots on a movie: sometimes it was the 21mm, sometimes the 24mm, and other times the 27mm.

JON FAUER

Is there more pressure lately from producers to work faster and therefore increasingly with zoom lenses?

(PETER SUSCHITZKY

I think that’s generally true, yes. But, I’m a prime person. I like the discipline of working with primes and optically they seem to be a little bit better. Although the Angénieux zooms are superb and it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference. I think they’re the best I’ve used. Angénieux have a really good range of zooms. They have a very fast stop. But I generally wouldn’t want to work wider open in T2.8 anyway.)

JON FAUER

Let’s talk about your career. How did you get started in film?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I’d have to go back to my childhood. I was surrounded by images. My father, Wolfgang Suschitzky, was both a photographer and a cinematographer. He would come back from work with Cinex Strips. The laboratory used to give the Director of Photography these test strips with the same image reproduced 20 times at different densities–from completely washed out to too dark to see. The cinematographer could then choose which printer light to indicate to the laboratory. My father would give me bits of film and I built a toy cinema. I put a bit of film in a gap between two blocks at the back of my room, and put a flashlight behind it, and imagined myself in a cinema looking at a movie. My father also photographed us children a lot so I was very aware of cameras from an early age.

JON FAUER

When did you first pick up a camera?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I was given a camera probably at the age of six. It was a Brownie Box Camera.

So I started to take photographs when I was very young. I also had access to the darkroom in which my father used to work at home. I wanted to emulate him and take pictures myself. I became fascinated by the image when I was very young.

JON FAUER

You went to film school?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I continued to take photographs into my teenage years and I’m still taking photographs. But I became reasonably competent at it by the time I was 15 or 16. By that time I’d already been developing and printing my own photographs but I was actually more passionate about music. That’s been one of my main interests. It’s not my only interest, but one of the great passions of my life has been classical music. I thought of studying music when I left school. But my father encouraged me to study film and become a cinematographer because he could see that I had a certain talent for it and perhaps I realized that I didn’t have enough talent as a musician to swim to the top or near to the top.

So he said, “We’ll find a film school for you.” There weren’t many in those days. There wasn’t a single one in Britain. There was a school in Prague and another in Poland, one in Brussels, and one in Paris. And, of course, the United States already had some film schools. He suggested the one in Paris. I already had some (the rudiments of )French because I’d studied it in school. I went to Paris and sat for the entrance exam and managed to get in. I wasn’t a very good pupil. I was an impatient young man and wanted to start working and getting experience in film. I realized that I wouldn’t actually learn a lot in film school, and that I could learn a lot more by working. So I left school after a year and started to work in films as a camera assistant. Since I was a very bad assistant, it seemed necessary (for the sanity of the DPs with whom I worked) for me to become a DP myself. I didn’t spend long as an assistant and I was lucky to get my first job as DP in documentaries at the age of 21.

JON FAUER

Why were you not a good assistant?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I can only imagine, looking back, that I wasn’t totally interested in being an assistant. I wanted to be the one who decided what the film was going to look like.

I think I must have invented a lot of mistakes that nobody had ever thought of.

JON FAUER

You left the changing bag open and jammed the magazine?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

No, I didn’t do that but I did send the wrong piece of film to the lab. The 1000 foot magazine had two sides, the exposed and the unexposed side. I managed to send the unexposed film to the lab. Luckily I canned up the exposed side. The next morning I realized my mistake and sent it to the lab. Another time, I also managed to load the film the wrong way around. And a few other disasters.

JON FAUER

What was your first documentary?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It was on the strength of my still photography that I was invited to become a cameraman in documentaries. I was engaged by a German TV company to make documentaries in Latin America and I spent a year in there as a one-man unit with a journalist. I did both camera and sound.

JON FAUER

What camera was it at that time?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I was using an Arriflex 16S.

JON FAUER

What happened next?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Still being slightly restless, after a year I decided that I’d had enough of shooting reality. I was always interested in feature films. I went back to England in the hopes of getting a job in a studio as an assistant on movies. But I was very fortunate that didn’t happen. Over the years, I had developed still negatives and printed them. I showed them to an editor friend of mine, Kevin Brownlow, who’s now an expert on silent cinema. He said, “These are terrific. But I’m actually making a movie on weekends. And I need a cameraman. Would you like to help me?” And I said, yes. It was a fictional film, imagining Britain occupied by the German forces during the war. I did that for half a year, on weekends and sometimes during the week. It had a miniscule budget. We shot on short ends that Kevin managed to get from Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove.”

Although that film was made for very little money, it was bought by United Artists and was shown in central London. It was like having a calling card. I could say, “I’m only 22 but I’ve shot a movie.” I began to get work on short films and commercials. Finally, a young director who was about to make his second movie, was also looking for somebody to shoot it. He picked me. His name was Peter Watkins. It was called “Privilege.” It was about a pop singer being manipulated for political reasons. From there, I was very lucky and didn’t realize how lucky I was. Once I’d shot one film, I was off shooting another one. Albert Finney was doing his only movie as a director, and I shot that. It was called “Charlie Bubbles.” Then another one came along and it just didn’t stop.

I was a very lucky young man. It was totally unheard of for a DP to be less than 35 or 40 years old in those days. It was a very hierarchical business. You had to pass through each stage of being a second assistant, a first assistant and then a camera operator before you got the break to be, if you were lucky, a Director of Photography.

JON FAUER

Were you in the union?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Yes, there was an obligation to be in the union. You couldn’t get a job without being in the union and you couldn’t get into the union without having a job. It was a little bit tricky to get in. But I did join before I got my first movie.

JON FAUER

Of the films you have shot, which are your favorites?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

One has to be very lucky to shoot really good movies. I’ve been fortunate enough to have done a few movies that a lot of people liked and I liked them too.

JON FAUER

Such as?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

“The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” And the movies which I have shot with David Cronenberg. Then there is “Mars Attacks!” which I shot with Tim Burton.

JON FAUER

Let’s talk about the relation between the cinematographer and the director. You seem to be a repeat customer with some of these directors, so you must be doing something they enjoy or like.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

The only long relationship I really had was with David Cronenberg. I shot two films with John Boorman but they were separated by 20 years, so it wasn’t exactly a marriage. Whereas with David Cronenberg it was very much a professional marriage. It was a wonderful opportunity to develop a relationship with him and shoot so many films together. Each one presented a different challenge. Each was quite different from the previous one. I found them all very stimulating to work on. For me, the key is to be stimulated by the project regardless of whether it’s going to be successful or not. I’m a firm believer in the importance of the context of what we cinematographers do. I think it’s pointless to think that you can do beautiful work on a bad film. Perhaps you can do good work on a bad film but it’s not going to have much meaning. Whereas if you do quite good work, maybe not great work, on a really good film, people will think you’re great and at the same time you’ll be stimulated. Actually I’ve found that I’ve done my best work on the most challenging films. Films which have been most stimulating to work on.

JON FAUER

Are you pretty critical, when you read the script, whether you’re going to do it or not?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Yes, I am. I would base the choice on the director, of course, and on the script. The script is really the backbone, the skeleton of the film. It’s ultra important. I think it’s possible to make a bad film out of a good script but I don’t think it’s possible to make a good film out of a bad script.

JON FAUER

Take us through the process of how you prepare for a film, how the style or the “look” evolves.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I would always give a disappointing answer to that sort of question. In brief, I don’t know. I absorb things into my soul, into my body and into my brain. I very rarely go into a film knowing exactly what I’m going to do. My personal method of working is very instinctive.

JON FAUER

It depends on the day, your mood, the available light conditions?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

No, it depends on a slow build-up. It is a patchwork of information that I absorb from, first of all, the script. It might be also come from talking with the director. With David Cronenberg, I never used to talk much at all. It would depend on seeing the locations. Getting a feel for the actors. Looking at the wardrobe. A whole bunch of different stimuli that I need to receive. Just getting a general, vague feel for what I think the film might need from reading the script again. I try not to repeat myself. I try to do something slightly different. Not deliberately different but something that’s appropriate to the film and comes naturally to me. I certainly would never start a film saying I’m going to use this filter or make it look like that movie or that painting. It comes instinctively and it’s got to fall into place on the first day because the way you shoot the first few shots is going to be the way you continue to work. I don’t have a self-onscious, calculated way of approaching a film.

JON FAUER

Do you make notes in advance in the margin of the script?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Very few. If I have queries, I’ll make notes about things I need to discuss with the director. Or about equipment, the number of shots needed in the scene, the time of day, or the lens. But I don’t make many notes. I used to write more notes than I do now. I leave myself open. I do the necessary amount of preparations so I’ve got the right type of equipment for the job. But I like to leave myself open to being stimulated by the day, the location, the actors and what the director might have in mind. Sometimes the director doesn’t know exactly what to do. That can happen too. Often, I am not sure what I’m going to do until I start doing it.

JON FAUER

Talking about choice of equipment is always interesting to me. Do you chose different things for different jobs?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Obviously I have to chose the camera well in advance. There are so many choices today whereas a few years ago with film there were very few choices. I might well suggest testing cameras side-by-side to see which one gives the result we like best. Then I have to choose lenses. If we are shooting with a digital camera, because they record so many details, my tendency is to go for slightly older lenses.

I chose the Primos on my last film because I love the way they resolve SKIN (faces. ).They’re not too cruel and they’re not ultra contrasty. I like them for that.

JON FAUER

You were the first one to actually use the F65 camera on “After Earth.”

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It was the first production to use it and it produces a terrific image.

JON FAUER

Please tell us about your approach to lighting. Is it also spontaneous?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It is spontaneous. Of course, I have to prepare and order the equipment. I need flexibility and sufficient lighting for each location or set. That doesn’t mean that I order more equipment than any one else! You can’t afford to be totally spontaneous and you can’t arrive with 10 trucks full of equipment. I have to make choices and know approximately what I need. I will start lighting and I will not be 100 percent sure what I’m going to do until I’ve finished. I don’t make a totally concrete lighting plan. I can say approximately what I’m going to do and then I have to be able to do it in layers. I’ve tended to become more simple as I have evolved. I was looking at a movie I shot 30 years ago called “The Public Eye,” based on the photographer, Weegee. It was shot in a film noir style. I must have used 20 flags in the very first scene. I don’t do things as time consuming and complex anymore. That many flags certainly makes it difficult for the actors to get in and out of the set, for a start. But it looks interesting. I was quite surprised by how good it still looks.

JON FAUER

When you’re shooting digital, does that affect the way you are lighting because of the higher ISO?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Yes, it gives me more flexibility. The first time I used digital cameras on a feature was on “Cosmopolis.” 90 percent of it took place in a limousine. I knew ahead of time that it would be, in many ways, the most difficult picture I would ever do because there’s so little room in a car to hide lamps. I was able to use little LED strips and the smallest incandescent light or a Dedo light as the main source. Bounced off a little white card hidden behind a seat. Things that I wouldn’t have been able to do on film. Digital gave me tremendously flexibility. Compared to what we had on film at 100 ASA, it’s very easy because you don’t have to work the shadow areas to the extent that we had to in those days with slow film. It’s much easier for the DP and you can see what it’s going to look like straight away. If this means that some of the mystery and power of the DP has disappeared, the trade-off is one which I am prepared to accept.

00:39:08:00 JON FAUER

If that was the toughest film you shot with Cronenberg, which was the most interesting?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

They were all interesting. None were easy. I don’t make life easy for myself because I’m very tough on myself and I’m always trying to do something that I haven’t managed to do before, always pushing myself. Some of the most stimulating were “Crash” and “Naked Lunch,” I think. They were so unusual.

JON FAUER

“Crash” couldn’t have been easy.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

No, but I laughed every day, somehow. It was very tough and the night exteriors were shot in the beginning of winter in Toronto. It got very cold and unpleasant. But I knew I was shooting a fascinating movie, so I was very happy.

JON FAUER

Who is coming to Cannes for your Pierre Angénieux Award event?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Matteo Garrone, the director of my last movie, “Tale of Tales.” Juliette Binoche is coming. Alba Rohrwacher, a very talented young Italian actress. Viggo Mortensen and Valeria Golino, who is also on the Cannes jury. I don’t have the full list yet.

JON FAUER

Could we discuss your work with Matteo Garrone on the last film–how he found you, you found him, and how it was working together.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I was driving my car and got a call directly from Matteo Garrone. Luckily, I knew exactly who he was because I see a lot of movies. I was an admirer of his movies. I pulled the car over and had a conversation with him. The English producer, Jeremy Thomas, had recommended me.

I went to meet Matteo in Rome. On my second meeting I said, “If you want to shoot your upcoming film like your previous ones, maybe I’m not the right person for you because you seem to move the camera in all directions, which means that there are very few places for me to place the lights. I’m worried that the lighting will not produce a very interesting result.” He replied that every film has its own style and I’ll adapt. It was a little tough because he came from a semi-documentary background and I came from a more traditional school of filmmaking. I like to know where the actors are going to be, funnily enough. He didn’t want to know where the actors were going to be. Matteo said, “I’m going to tell them they can go wherever they like and we’ll follow them.”

JON FAUER

How did you resolve this lighting question?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

It was difficult. But I can say I’m extremely pleased to have shot the film.

JON FAUER

You worked with Ms. Binoche on “Cosmopolis.” Do you change the way you light different actresses and how do you make tests?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I try to do tests–at least half a day shooting with the actors who are going to be in the film. Of course, I want the women to look their best. It’s always an instinct, is it not? I don’t want to use special filters on the camera.

JON FAUER

It’s interesting that your family has three generations of cinematographers. I think it was another cinematographer, Tony Richmond, with many sons and family member in the business who said “Nepotism is fine as long as you keep it in the family.” Is it unusual to have such a long family history of cinematography as yours?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Yes, I think it is. I fell in love with cinema and being involved with telling stories when I was very young. My son Adam came on some of my movies as a trainee and took still photographs when he was a teenager. It seemed natural, although he did tell me when he was 16 that he wanted to become a war photographer. I strongly advised him against that.

JON FAUER

What motivates you most?

PETER SUSCHITZKY

The quality of the script is most important because I want to work on good projects. That’s always been my ambition. I’m interested in many other things that I think have enriched my life and probably indirectly affected my work as a cinematographer. I love music, painting, literature, cooking and wine.

JON FAUER

And still photography.

PETER SUSCHITZKY

I brought out a book of photographs last year, “Naked Reflections.” It’s a collection of two types of photography. I’ve always done street photography. I stopped doing that about a dozen years ago. I decided to try something I could do at home. I gave myself the crazy challenge of doing black and white nude photography: crazy because many thousands of people have done it. My doubt was that I might not be able to find my own way of doing it. I hope I have. The book is available on at Amazon. You can see some of it on my website. (petersuschitzky.com)

JON FAUER

In summary…

PETER SUSCHITZKY

Whatever the technology and its advances, the fundamental thing in filmmaking remains the idea and the script. I like to feel free when I start a movie, unencumbered by too many preconceived ideas. I want to be able to react freely to what I see on the day, even if I have made plenty of preparations. I have always, since my childhood, been obsessed with the image.