This is a discussion about the making of F1 with the following cast of characters:

- Claudio Miranda, ASC, Cinematographer on F1

- Dan Ming, First Camera Assistant / Systems Engineer on F1

- Nobu Takahashi, Head of Sony’s Cinema Line Division

- Tanya Lyon, Sony Cinema Line Marketing North America

- Shunjiro Nishi, Sony Mechanical Engineer

- Koji Morioka, Sony Mechanical Engineer

- Kenji Sasaki, Sony Mechanical Engineer and F1 Camera Support

- Kohei Suganuma, Sony Electrical Engineer

- Keita Yasui, Sony Public Relations

Jon Fauer: You, Claudio, seem to enjoy pushing the limits of camera technique and technology on big blockbuster films. How were F1 and Top Gun: Maverick different?

Claudio Miranda, ASC: One of the big differences between F1 and Top Gun: Maverick is how camera placement influenced the actors’ performances and how we could control the cameras in real time. On Top Gun: Maverick, the actors didn’t really need to see where they were going. A pilot was flying the jet in the front seat and the actor was sitting in the back seat. Also, we weren’t able to review the action until they landed. That changed on F1. We wanted to see where they were going in real time, live, around the track and we wanted to have them to see where they were going because the more they could see, the faster they could go.

I understand that Brad Pitt and Damson Idris drove modified F2 cars at speeds up to 200 mph. Leading question: why not just film against virtual backdrops?

Claudio: We weren’t really interested in using a volume with virtual backgrounds. Those would have been sad versions of this movie. I visited Mercedes and showed them everyone’s smallest cameras, like a RED KOMODO, a Sony FX6 and FX3.

I talked to Tanya Lyon at Sony, who put me in touch with Nobu Takahashi and the imaging team. I asked them, “Is there a way to basically make us a sensor on a stick? Just how much can you trim away and how small can you get it and can you build it so people can see where the actors are driving and, oh yes, can we pan the cameras and how do we do that in a network setup around various race tracks around the world?”

I went back and forth with Sony and they showed us what they could do with a camera system combining features of the FX3 and FX6 along with the remote camera operation capability derived from FR7 technology, but configured differently. Basically, Sony tore apart the FR7 and then we had a discussion about how long they could make the cable connecting the camera head to the body. I think Dan Ming (1st Camera Assistant and Focus Puller) initially wanted 20 feet and it ended up around 9 feet.

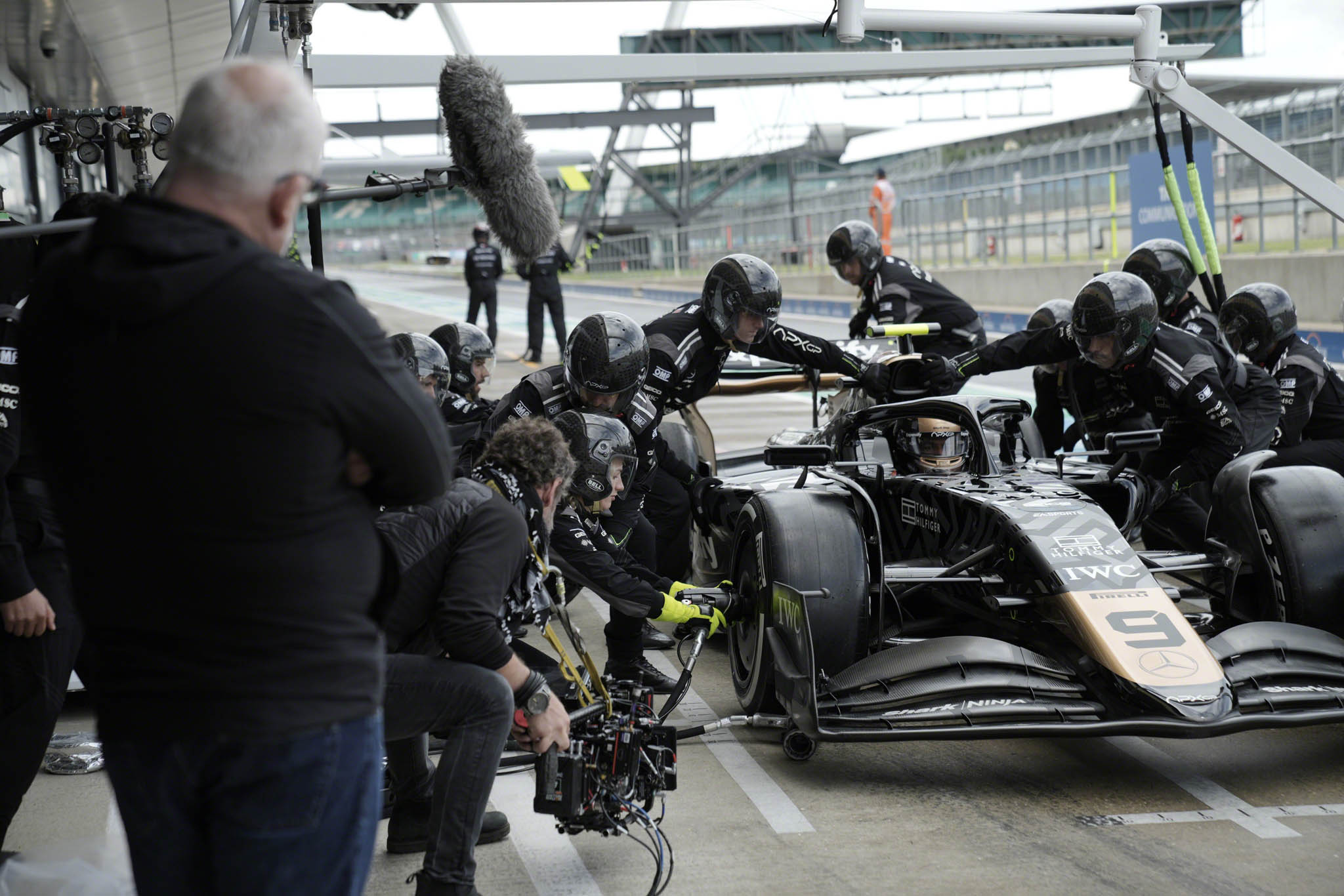

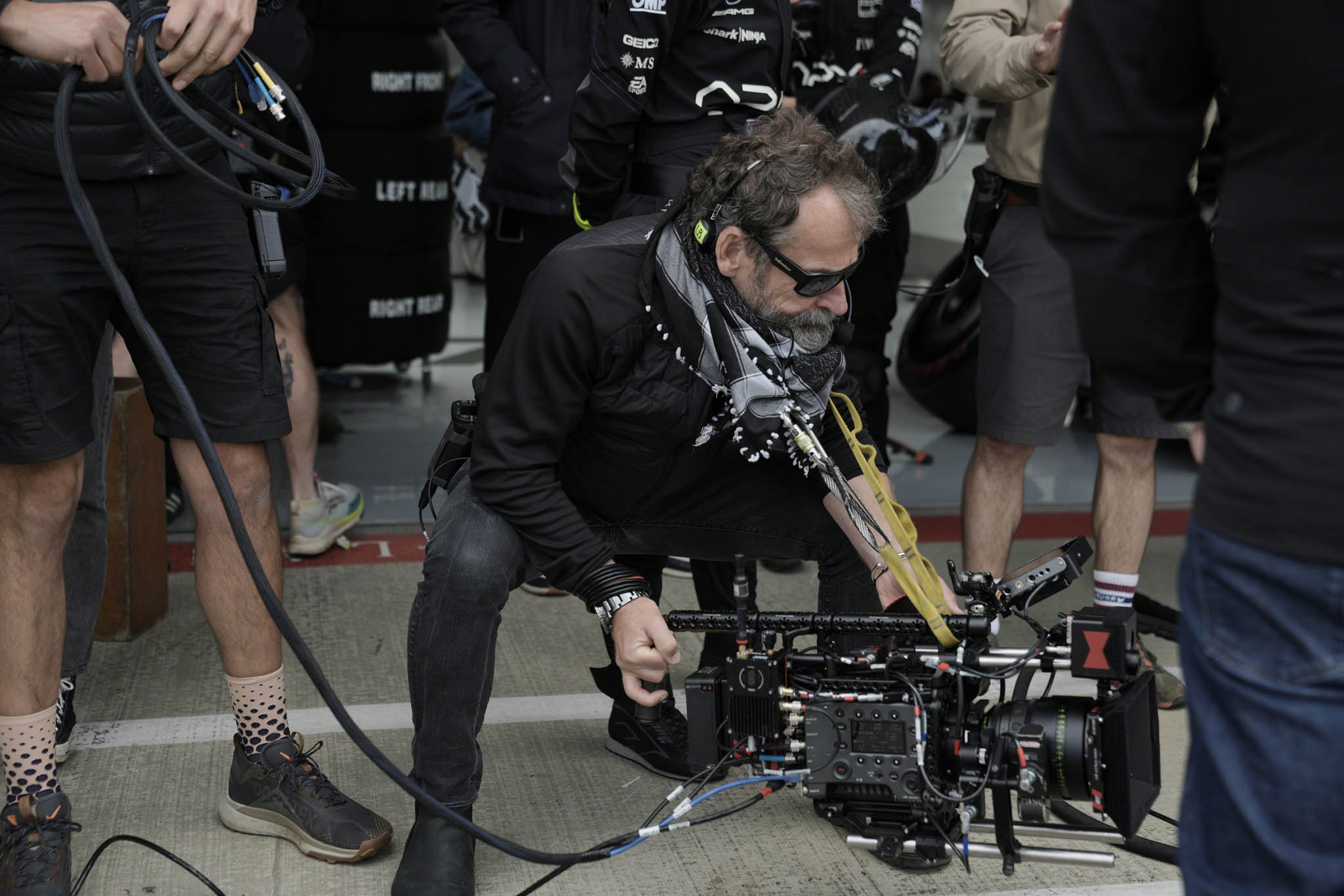

We had so little room to play with. For Dan, it was like working on a puzzle, trying to figure out how all this stuff fit together. Before it actually went into the cars, he was putting all the pieces out on the floor to see how it would all connect and work.

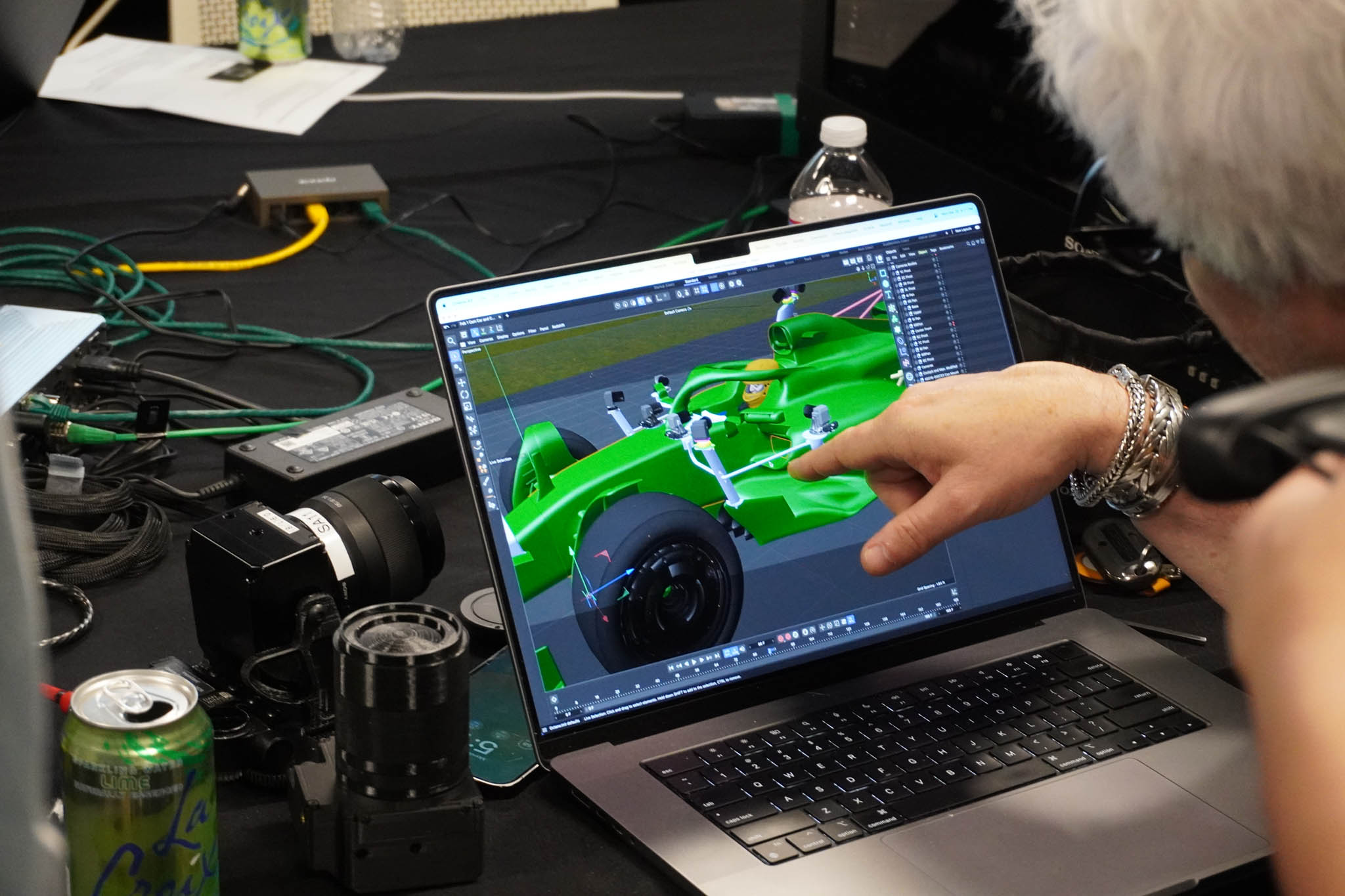

Dan Ming: Mercedes said, “This big camera is never going to fit in the car. The engineer who was laying it out via CAD said, “You guys figure it out.” So we did—we just had to figure it out, and Sony made the cameras smaller.

Claudio: It was the same thing on Top Gun. The guy said “You’ll never get more than one camera in the cockpit.” And we got six. The F1 guy said that we wouldn’t get any more than one camera inside and we got four, which is still pretty good considering the actors had to drive.

Sony built more than 20 of these little cameras for us.

Normally we didn’t pan more than two cameras, even though I guess we could have gone crazy and panned everything, but certain positions, like the center front, would not pan because we needed it to be as small as possible. That was a specific mount. The driver had to turn the steering wheel and see off to the sides, so we even shaved some of the cosmetic parts of the halo off the car. The halo is a primary safety structure for the driver. We did not cut the actual halo itself.

We shaved parts of it to get it further away from the steering wheel and all this had to be approved by Mercedes: the camera, the rigs, the cabling. Also, to help the driver, we had a little half-inch riser so they could see a little bit underneath the camera and give them a little more peripheral visibility.

I have to say, of all the companies out there, and I’ve worked with many, I just feel like the only one that actually could have come through with something like this was Sony. With anyone else, I just had the feeling that it might’ve taken until next year to engineer such a tiny camera and we didn’t have until next year.

Dan: Our timeline in prep was 6 months to work this all out. We got the prototype from Sony in 4 months.

Essentially you wanted something even smaller than a Sony Rialto (VENICE Extension Unit) and the Rialto Mini hadn’t even come out yet? You wanted a Rialto micro Mini?

Claudio: There was no room inside the cars for VENICE camera bodies. Basically, we needed to strip it down to a camera head just slightly larger than a sensor that could be panned, with a little plate and a lens mount, tethered to a small body.

Why not use a Sony FX3 on F1?

Claudio: We didn’t want IBIS (in-body image stabilization), among other reasons. And even the FX3 was too big.

Top Gun: Maverick came out in May 2022. When did you start prepping and talking about building special cameras for F1?

Nobu Takahashi: Our first discussion with Claudio and director Joe Kosinski was in November 2022. Claudio asked for something like “a sensor on a stick.” The Sony team included Mechanical Engineers Shunjiro Nishi, Koji Morioka, Kenji Sasaki; Electrical Engineer Kohei Suganuma; and many more. The first mockup was delivered in February 2023 and the first prototype came a month later. Test shooting began in April 2023 and the cameras were delivered in May 2023.

Claudio: Filming with these cameras began in June 2023 at Silverstone and followed at tracks around the world through November 2024.

Jon: Why does Sony take on these daring projects of Claudio? Most manufacturers wouldn’t want to modify their beloved products to such an extent.

Nobu: I always like to challenge our engineers to become excited and do whatever they can. That’s a very strong message. It is always exciting to work with Claudio. We had a similar experience working with him using the VENICE camera on Top Gun: Maverick. So we were very confident and happy to support Claudio and Dan Ming on this project. It was that simple.

Please describe the “sensor of a stick” concept in greater detail.

Claudio: The F1 actors had to see where they were going because they were actually driving the cars. As mentioned, on Top Gun, the pilot was in the front seat and the actor was in the back seat, acting like they were flying. The VENICE Rialtos were mainly for these angles on the actors. And we also had reverse angles, over the shoulders and POVs of the real pilot. So, Tom Cruise had a control stick, and because he didn’t need to see where he was going, we could put a blanket of cameras in front of him.

But on F1, it was very important that Brad and the stunt drivers could see where they were going because the more they could see, the faster they could push the cars. If they became unsure about visibility, they would just slow down. It’s not like putting a big camera in there and they would go safely around the track at 30 miles an hour. That’s so unexciting. We were trying to get the cameras running as they were driving over 180 mph and the stunt guys were hitting over 200 mph.

That sounds like an extra responsibility: keeping the actors safe from flying camera parts.

Claudio: With the actors actually driving, I was worried too. That’s the main reason the cameras had to be made as small as possible. There was no other choice. When Brad got in the car the first time, he said, “I don’t know about this.” That’s when we added a little riser that helped his visibility and he kind of felt better about it. Then he and stunt drivers got used to it.

I assume you rigged cameras on many cars, to be ready right away. How did you keep track of all the cameras?

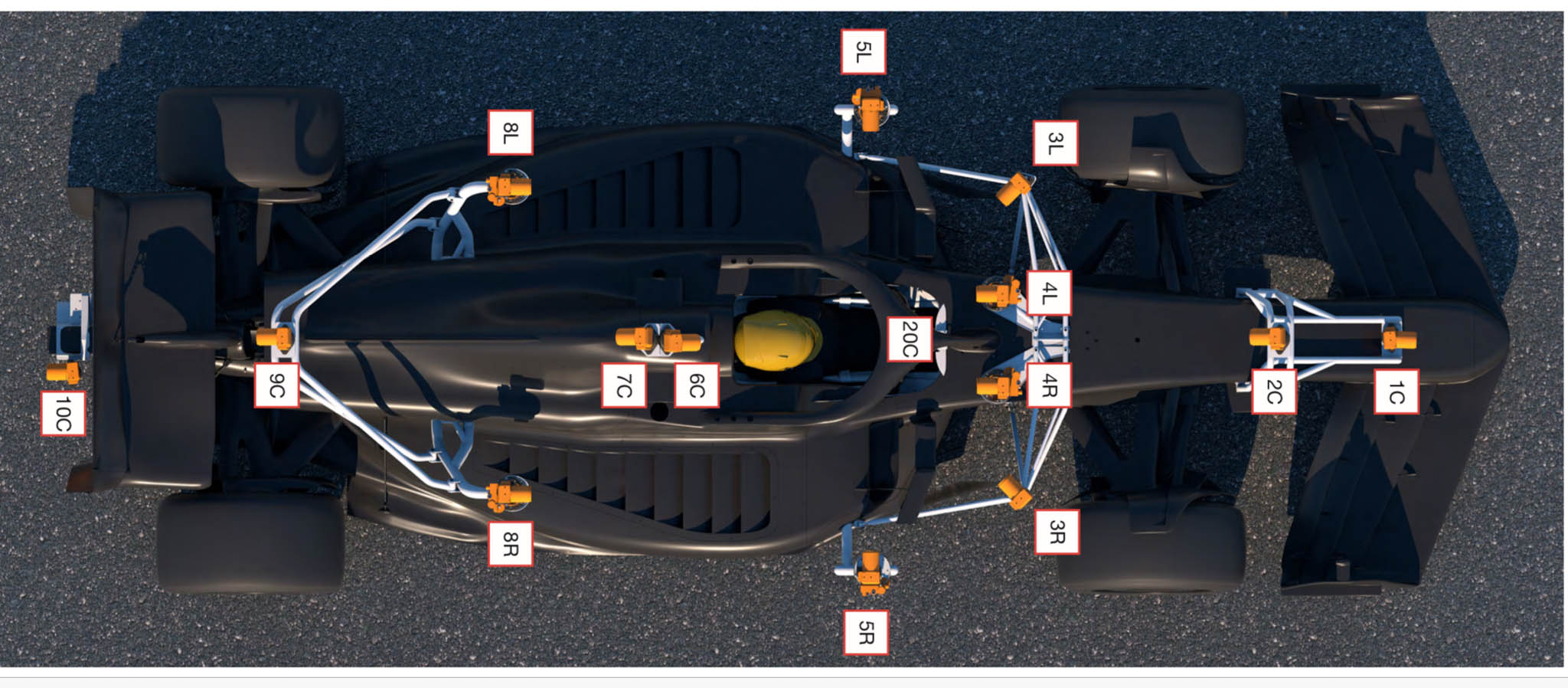

Claudio: We identified them by their positions, from the front of the car to the back. 1C is the center nose mount, facing forward. 2C is front center, facing back. 3L and 3R are three-quarter views facing the driver while 4L and 4R are on each side of the driver, also facing back. And so on.

Those are the camera positions and they are labeled based on the mounts that did. For the last race, I was getting kind of bored with all these things, so we made another mount called 2L and 2R that go over the tire looking back, which is used in the finale.

Dan: This is a view of what the driver saw: 20C in the middle and the riser with its gap underneath.

That’s pretty scary. The driver can barely see anything.

Claudio: We tried our best to make it so they could see something, and riser was really helpful.

Please take us through the choice of cameras.

Claudio: Initially, we looked at a bunch of different versions of the cameras and sensors. We knew that we wanted internal NDs. We didn’t want mechanical variable ND filter wheels because they take up more room. There was talk about adding an extra half inch to the camera size. But really, a half inch was too much. So the Sony team built an internal filter slot between the lens mount and the sensor, as well as 8 ND filters per camera that could slide in. They said it took something like one hour to make each one.

Dan: We had Clear, ND0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, 1.5, 1.8, 2.1, and 2.4.

Was this an early version of the Rialto Mini with its drop-in rear filters?

Claudio: No, Rialto Mini was not on F1. But the filter concept is similar.

Nobu: They called this camera “Carmen” as a nickname. Like Carmen Miranda, the famous singer, dancer and actress.

Claudio: No relation. But the last name is good. Why not? That’s what we always called it on location. Even Joe called it Carmen.

Nobu: The camera is a special prototype for the F1 film. It has the picture performance of the Sony FX6 and FX3 cameras with the remote operating capabilities of the Sony FR7. The camera head is separated from the body and connected by a tether cable. The remote control pan base was created by Panavision. Dan Ming can explain how the camera system came together.

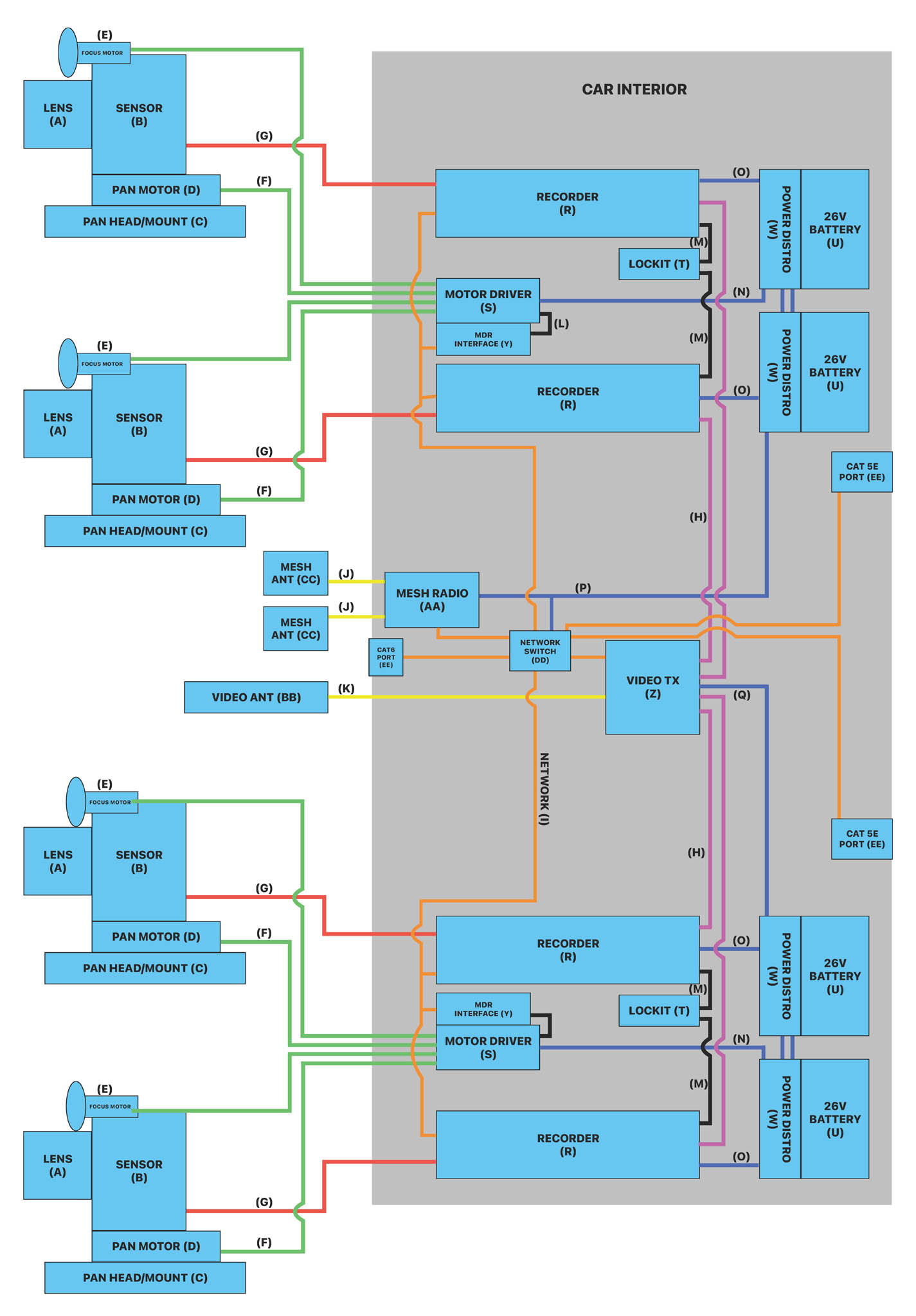

Dan: My job was basically breaking down Claudio’s call explaining what he wanted and putting those ideas into a workable system. He said, “We might have up to four cars, and we’re going to have four cameras per car. We need to see the pictures from all the vehicles, and be able to start-stop each camera. You need to pull focus, we need to pan the cameras and we need to do all that simultaneously on multiple tracks around the world.” So, that’s how the conversation started.

As Claudio mentioned, he was in conversation with Sony about the cameras. The form factor of the camera was evolving, so we designed the panning mechanism around 3D models. To keep things simple, we wanted to drive all the motors with the Preston Cinema Systems Hand Unit and MDR, so Claudio sent me a drawing of a pan head using a Preston motor. We then added another Preston motor to control the focus.

We got together with Panavision and built the head. Once we did that, we had to get the Preston wireless focus and pan system working remotely.

We went to RF Films to adapt their system that converts Preston serial protocol to network IP, which was then switched into a local network in each vehicle with the FR7’s Internet IP and other system components.

Each car was its own mesh node and RF Films created a mesh network around each track where we filmed. The network connected to mission control. That way, we would monitor each camera from each car in real time around the track. My job was systems integration, figuring out how one thing communicated or interfaced with the next making sure that they all worked together. We were careful in the design process to minimize any incompatibilities, so that they would be ironed out early on as opposed to when filming began. The video transmission and receive network was handled by Hornets-Tech and Wireless Wizards in the UK.

How were you panning the camera with a Preston Hand Unit?

Dan: We used eight Preston HU-3 Hand Units paired with Preston MDR-3 Motor Drivers, which have four channels. Each camera pair was assigned an MDR-3. RF Films built custom knobs for the operators to pan with and we had the lenses mapped to the handsets for focus, all hard wired into the network.

Which channel was controlling pan?

Dan: Focus usually, because it has the most amperage.

How do Preston MDRs connect to the mesh network? WiFi?

Dan: That was Greg “Noodles” Johnson of RF Film based in LA. They had previously extended Preston FIZ systems over IP on other projects. That is another reason why we built this around the Preston system because I knew that technology and camera control had already been figured out to channel it through IP.

Nobu: The Prototype Camera for the F1 movie had the picture performance of FX6/FX3, but leveraged the very good remote control technology from the FR7.

Dan: Which saved us. The FR7 protocols really made it workable for camera control.

What lenses were you using on Carmen cameras?

Dan: Many. For wide angles, we had Voigtlander E-mount primes—10mm, 12mm and 15mm with declicked irises. Our longer focal lengths were ZEISS Loxia E-mount lenses.

Claudio: It was critical to put the ND filter behind the lens because it would have been difficult to put a filter in front of the 10mm Voiglander. An unfortunate thing was our lack of a protective front filter on the 10mm lens. We went through 20 or 30 of them.

Dan: We basically just had to throw them away when the fronts got damaged, which was sad. Those lenses were beaten up.

Did the internal, drop-in ND filters inspire the Rialto Mini ND system?

Nobu: Yes, that’s true.

Dan: One of the things we asked was whether they could have put an electronic ND inside, but it would’ve made the camera bigger. So it was a conscious decision to do that because it just had to be as small as possible.

Where are you two, Claudio and Dan, operating and focusing?

Claudio: Mostly in mission control. We were like the 11th F1 team, in the 11th team slot. We moved around between different places. Sometimes we were around the track, shooting our exterior scenes. And then we’d go back into mission control, which was in back of the pit area. When the real races were going on and the teams were there, we would work in the front of our garage and that was kind of our set. Sometimes we were off in another garage, but we always had a mission control of some sort to view all the cameras.

It was also a place where Joe could talk to the actors and the operators who were working the pans. Often, it was quite busy.

Dan: This is an example of what we were looking at. Here we have four separate cars, with 14 of our 16 Carmen cameras going at the same time. Sometimes we had five cars going as well, with 20 Carmens to work with. Since our network would only handle up to 16 cameras at the same time, sometimes we would spread out 16 cameras over five cars as well.

Claudio: But a lot of times, you could see one team running and another one was getting ready to go out. There was a lot of leapfrogging. I could also go check and see how the other cameras were doing. For example, we’d be on Brad racing while they were getting ready for Damsons—since they didn’t run together at the same time. They were running against stunt drivers. Our windows of filming were very short, so the one set of cameras would come in and then the other ones would go out. It was very ambitious.

Dan: Early on, we were still getting a feel for what we could get. It was like, why not roll 16 cameras on four cars? And so we did. Then we realized that there were limitations. Congestion of the network slowed down performance and increased latency. Cameras were getting in each others’ shots. Also, F1 races are so crowded in terms of RF that they gave us just a very small slice of bandwidth. We had to work all our systems within that bandwidth and so choices had to be made.

Were your cameras in the cars running during actual races?

Claudio: Not during real races, no. But at race time they would give us a slot sometimes before and after qualifying runs. We would never run our cars during a race except one time when we got really close to a race start.

Dan: Our cars were on the back of the grid and all the other cars started in front of us.

Claudio: And then we had to run our car really quickly. We had a minute or something to get everything off the field before the rest of the cars came around again. We were a little embarrassed because our car stalled. We had to push it off the track. They were like, “You newcomers, you film people…”

How many camera operators did you have, panning with Prestons?

Claudio: Four was our maximum. We averaged two. Sometimes I would jump in and be the third camera operator.

How many focus pullers were in these massive setups?

Dan: Up to four focus pullers.

Claudio: Many cameras were lock-offs, like 20C on Brad. But if they had to pan from Brad, going from 4 feet to 50 feet, that would be a bit of a focus pull.

Flashback to the development process. Please take us through the timeline again.

Nobu: We had several video meetings between November 2022 and February 2023 with Claudio and Dan, exchanging data and feedback. In February 2023, I met with them at a Sony facility in Los Angeles to show them a 3D-printed mockup that looked like a black brick. We met again in March 2023 at the Sony DMPC in Glendale with the first prototype.

Prep began at Panavision the same month.

We had the first test filming in April at Willow Springs in Rosamond, CA (America’s oldest permanent road race course) and delivered the cameras in May, which was six months after the initial request.

We provided 20 cameras (we just called them prototypes for the F1 movie, until Claudio called them Carmen).

This is the original design of the camera that basically has the performance of an FX6/FX3, but with a smaller camera head, and tethered to the recording box that also has very good remote functions derived from the FR7, as I mentioned.

One small detail is how we made a small cut on the right rear corner so the camera would clear the halo on the car. I remember Claudio was playing around with the CAD design to shave off parts of the camera and the car’s halo as well.

Claudio: We needed still more room, so they made a little cut and we shoved it back further. But normally there’s a plug that when they are racing, it covers that area.

Were you developing the VENICE Rialto Mini at the same time or did that happen later?

Nobu: Actually, we were working on the VENICE Extension System Mini (Rialto Mini) at the same time and we had discussions whether Claudio would prefer that. But the VENICE Extension System Mini (Rialto Mini) camera head was thicker at that time and would not have fit under the halo.

When did you meet with Mercedes?

Claudio: I met with Mercedes really early on, in January 2023. These cameras weren’t around yet. I told them I’m working on something and they were all just saying, “No way.”

How was Sony able to deliver a rapid prototype so rapidly?

Nobu: The reason we could deliver an early prototype within a very short period of four months is that our engineers had already been thinking about some of these concepts. We have a yearly Sony Bottom-Up Event where engineers do some crazy things to demonstrate the seeds of technology concepts that they would like to see in future products, including cine cameras. So that’s how it developed very quickly.

Dan: I can add another reason why we went with the FR7 “brain” form factor: it is because the recorder is much more compact and much more power efficient. If we had to use a VENICE 2 body on the other end, I don’t think it would’ve fit inside the cars.

How did you start and stop recording picture on all the cameras?

Dan: RF Films built boxes to trigger everything. We used the Sony VISCA protocol, which is in the FR7 and not in the VENICE system. The protocol in the FR7 was key to being able to have us control it remotely. (VISCA—Video System Control Architecture—is a protocol developed by Sony, used mainly to remote-control their PTZ pan-tilt-zoom cameras, that connects via serial RS-232/422 or IP networks.)

What was your recording format, resolution and media card?

Dan: XAVC/Intra 4K recording onto CFexpress Type A (same as with Sony FX6/FX3).

Nobu: The camera can also record to SD cards—we have two options, but for higher bit rates, we need CFexpress Type A. The media slots are in the camera body, not the head. They are tethered with a cable consisting of copper wires. The VENICE Extension System 2 (Rialto) and VENICE Extension System Mini (Rialto Mini) use fiber and copper. But for this special camera, it’s only copper wire.

Dan: Also, to run the cables, we actually had to open up the cameras and disconnect the ribbon cables from the circuit board. There were so many pins that any connector would’ve just made the whole thing too big. So, we elected to just connect the cables directly to the actual circuit board. Sony made extra cables for us. They worked very well. But these cables were not meant to be plugged in and unplugged multiple times a day.

Nobu: Our engineering team would like to add a few comments.

Shunjiro Nishi: Thank you. I’m the project leader of this prototype. As Nobu-san mentioned, at the Sony Bottom-Up Event, we showed an early prototype using the FR7 mechanical and electronic parts, which basically had the picture performance of FX6/FX3, as a tethered “long-neck” model. Then, Nobu-san asked me to make it much smaller—to be used for high-end Hollywood productions. I was really surprised and then bit scared because he said I had only one month to redesign it. I worked very hard to make it smaller and then showed the mockup to Claudio and Dan. I remember showing them two designs: a larger one with the internal drop-in ND filter and another smaller mockup without ND. Of course, Claudio said, “We would like the smaller version, but with the drop-in ND.” I was upset at first, but we figured it out because we had also been working on the idea of drop-in filters for the early VENICE Extension System Mini prototype. So we developed the final prototype to be small and to include drop-in ND filters.

Nobu: Filmmakers always give us lots of challenges, which we like.

You have to undo two screws to change filters in the Carmen camera. It doesn’t just pop open like the Rialto Mini?

Koji Morioka: We didn’t have time to make a trap door, as it is often called. So, we had to make an easier way to exchange filters and we went with screws. But, after receiving feedback that people didn’t want to use any tools, we implemented a quick release system on the VENICE Extension System Mini that shipped later on.

Dan: But for the Carmen cameras, they did make the screws captive. It was essential that these screws would not fall into the car or into the filter slot.

Nobu: Also, the VENICE Extension System Mini extension cable is detachable. That idea came from requests during this F1 project. Dan gave us advice, so it has a detachable cable system reflecting those requests.

Dan: And importantly, Sony engineers also made the Rialto Mini connection smaller, which was amazing.

This is a leading question that you may not want to answer. After the success of the F1 movie, everybody’s going to want this camera that cannot be named Carmen. Will it ever be available for the rest of the filmmaking world?

Nobu: At this moment, Jon, we don’t have any solid plans to productize it, but we always listen to users like cinematographers, camera crews and the market. We may think about it in the near future, but at this moment we don’t have any plans. But I know, it’s a really, really good camera.

If you do, and the name Carmen is out of the question, perhaps it could be named Claudio or Danny.

Dan: If you do, please make a lot of extra cables. Size was so important and it was designed in a way that might not necessarily be practical for a mass market. A user who’s not comfortable plugging ribbon cables onto a circuit board would probably prefer some sort of connector.

Claudio: And there’s no real monitor on the brain—the camera body. It’s all through the network. It’s not like a “normal” camera with a monitor, menu and record button. There’s no record button other than through IP.

Dan: We knew there was a timeline that was so critical. So we made choices accordingly, concentrating on doing the things that were most important and letting other things slide as long as the image wasn’t affected.

How did you involve Panavision for the pan mechanism?

Dan: They have a long history of manufacturing and were super excited as well. When I said we needed 20 of these heads, and showed them the design, they said. “OK, we can do that for you.” They put other projects on hold just as Sony jumped us up the queue in the manufacturing process.

Everyone did an amazing job. It became a matter of making sure that things all worked together. When Nishi-san showed us the first 3D-printed prototype, I asked him, “The holes aren’t going to change, right? Because we’re going to manufacture the heads based on this model, and if the holes move, then the entire head design will have to be changed.” The holes didn’t change. There was a lot of trust in each other and communication to make sure that it would all come together. Everything was timed to show up at the same time and we just put it together and it all worked.

Was this a Panavision job even before you started custom-making heads?

Claudio: It was a Panavision job because we had to travel to many locations. They’re a world-wide company, they’re everywhere. I also knew that Panavision has excellent machining expertise, and I knew we’d be machining things too.

Dan: If we were at a racetrack somewhere in the world and we needed an extra camera, we could just call Panavision and they were always nearby.

Did you use “regular” cameras? I assume you must have had them for dramatic scenes, long lens setups, not in the car?

Claudio: Yes. All the dramatic scenes were on VENICE 2. And helicopter work.

What other lenses did you use?

Claudio: On the VENICE 2, we were basically on Fujinon Premieres, Premistas, ARRI/ZEISS Master Primes, some Sigma Full Frame High Speed Primes and some Sony G-Master primes. On the Carmen cameras, as mentioned before, we had Voigtlanders and ZEISS Loxia primes.

Dan: It was similar to the Top Gun: Maverick lens package, except we added more Voitlander focal lengths because they were more compact.

Claudio: some of the lens choices on the Carmen cameras were influenced by their size. Some Loxias were longer than the Voigtlanders.

Dan: The length of the lens was critical, especially with the halo of the car. If the lens was too long, then as the driver was steering, their knuckles would hit the lens.

Your Master Primes covered Full Frame?

Dan: The image circle is large enough from the 50mm and above. Except for the 65mm. J

And the Fujinon Premieres also covered Full Frame?

Claudio: For the helicopters, I used Fujinon Premistas in Full Frame. On the ground, for long lens, we’d just go to 5.8K. Sometimes I like the way the 100mm looks on Full Frame. Sometimes we made an artistic choice to use the 100mm or the 150mm Master Prime. There were really beautiful in Full Frame. So we mixed formats. We wouldn’t say we have to shoot 5.8K. Sometimes we shot Full Frame for different reasons. Sometimes I would have the helicopter crew shoot a little wider just in case—in 8.6 K for the full width, and then we knew that we could always crop in or stabilize if we needed to.

Did you and Joe talk about the style and the look of the film in advance?

Claudio: At first, I was sad—because there was nothing I could do about the fact that they start many F1 races at noon, which is hardly a DP’s dream time to shoot. And then, the races are all at different places. Silverstone went from partial cloudy, to partly sunny to overcast. Abu Dhabi was actually a very interesting race. It starts an hour before sunset and then goes into night. Las Vegas was also interesting: the lights are dim, so it feels the fastest. The other tracks do stadium lighting from far away, so you don’t get that kind of staccato feeling.

Monza has a tunnel, so it goes from dark to bright. Spa-Francorchamps has a fantastic uphill stretch. All the tracks have their own little personalities and we were trying to shoot as much as we could in the short windows between races, around 2:15 to 2:30 pm. We went around the track and basically had front light half the time and backlight for the other half. Sometimes I’d say to Joe, “This corner’s really great at this time of day.” But mostly we were just shooting for action and I think it feels real. I’ll take all this real, natural light versus a beautiful golden-hour background on a volume any day.

Would you say that the style of F1 is realism?

Claudio: I’m always trying to get cameras smaller anyway. Top Gun was trying to get it smaller. I’d rather have a really great shot with a smaller camera than a big cinema camera in a volume. We are at a great intersection where I’ll take realism in a smaller form factor that has cinema qualities, which we did on F1. I think that’s what is exciting when you see the movie, You go, “Wow, this is really happening.”

We still want depth of field, so we still want lenses that have fall-off. If you get a shot where everything’s in focus, that is a little sad. It’s nice to have depth of field and have a person like Dan Ming pulling focus on it. That is awesome. And that’s kind of what we built. So the style of the movie, I would say, is immersive realism.

Jon: Did you refer to old movies? You mentioned Grand Prix. Did you and Joe look at old racing movies in the beginning during prep?

Claudio: We did. We watched Grand Prix, and then we love some of the speed on that, but that was more or less single camera footage. It was already huge. And seeing some of the making of Grand Prix was also not quite our safety zone.

And a young Otto Nemenz was a camera technician on Grand Prix, beginning his career at Panavision.

When Joe and I were watching movies, some did realism really well. Grand Prix did an excellent job. However, on other films, the exterior shots of the car look good but as soon as you get inside, it feels like you’re on a boat and they’re going at 12 frames a second to make the thing seem like it’s going faster. Everyone’s shaking and it doesn’t feel real or connected.

Also, F1 is really an exposed experience. You’re not just inside a car, you’re also out in the open. The onboard cameras really capture the whole adventure. If our car was going 100 miles per hour, it’d be too slow.

So the style of F1 is immersive realism?

Claudio: Immersive realism, yes. We’re getting away from the technology of the virtual world, which is amazing and especially great when you can’t really be there. But I still think it’s a second choice.

It’s how you felt and when Tom Cruise went off the ship in Top Gun: Maverick. In F1 you’re going to feel Brad’s driving, really driving, and you’re going to feel that Damson’s really driving. I remember when Joe went to watch the footage with the whole team and I thought, wow, this is going to be a room of very critical people. I was happy when they were all very complimentary about the whole thing.

Claudio talked about shallow depth of field. Did you use Preston Light Rangers?

Dan: Yes. For all the dialogue and VENICE setups, we had Light Rangers.

I have just a devil’s advocate question. Why couldn’t you use Sony FX3 cameras?

Claudio: Image stabilization. IBIS was not compatible. Also, the FX3 would have been too big, too wide. Carmen is even smaller than an FX3. I would say for size, if you just take the mounting point and add three eighths of an inch around it, that’s kind of it. It’s pretty much just the sensor, the lens mount, the mounting plate and a little room for metal and that’s kind of it. The FX3 was actually too big.

The Carmen cameras have Sony E-mounts. Did you lose any lenses flying off?

Dan: No. The only time we came close was when the vibrations actually almost tore the whole mount itself off. We had one time where the lens mount came off and was hanging on by the cables and at that point we actually re-screwed everything with Loctite and then we never had a problem again. But that was early on.

You were not eliminating vibrations, you just lived with them?

Dan: No, Sam Phillips, our key grip, and the car rigging grips took steps to minimize them and figured out that the best thing for that type of vibration was Sorbothane (a synthetic viscoelastic urethane polymer used as a shock absorber and vibration damper). Depending on how much we used or how tight we screwed into it, that’s how we tuned it based on each track’s individual characteristics. Some tracks were bumpy, some were very smooth, but they had a very fine vibration. Sometimes they resurfaced the track between one year and the next. Then the drivers would complain about the same thing, where it’s totally different. For us, it was how the vibrations translated to the camera and we how we had to dial ourselves into each track.

Claudio: Each camera’s car mount had different levels of Sorbothane. The most stable one that probably didn’t need anything was 20C in the middle. But as soon as you got more towards the edges, they required different levels of Sorbothane. Also, we knew that some cameras needed to pan. The only way to do this was non-stabilized and finding some level of rubber to take the edge off.

Dan: The Sorbothane was attached between the base of the head and where it was bolted to the car.

Nobu: We have been talking about the toughness of the cameras. If I may show some pictures—these show the conditions the cameras endured. A brand-new camera looks like this, very clean (below, left). After a few races, they looked like this (below, right). I’m very relieved that they survived.

How did they become so battered?

Dan: Basically, it’s like driving into a sand-blaster, along with rocks, dirt and things flying at the camera at 200 mph.

Claudio: That’s why we we’re going through lenses so quickly.

Nobu: And all the cameras came back safe, which is very nice.

Claudio: They held up amazingly well. Those cameras were such heroes on this job.

Dan: There were crashes where we’d have footage of it.

Claudio: We had a car crash at, I don’t know, 160 miles an hour and the cameras were still rolling.

Nobu: I would also like to thank Kenji Sasaki and the team who did a very good job of camera service support during the races.

as the Sony engineering team there the entire time for every race?

Nobu: Not the whole time but they were always available.

Kenji Sasaki: I did maintenance on the cameras two times during the shooting. It was a pleasure to have joined the team.

Claudio: We had to be safe and careful on this movie. We had to be really careful about our mounts and where they went. If there was a crash, the driver had to be protected. I couldn’t just come up with a mount and say, let’s just get the guys to attach some speed rail. Everything had to be approved by Mercedes and checked by Graham Kelly, who was in charge of the cars and driver safety.

Everything was super safety oriented on this job. It’s dangerous anyway, crashing at 160 miles an hour. But we couldn’t just say, “Oh, let’s just stick something out there for me to get a new camera position like the last one.” It took me two and a half months to get a new one approved.

We tried to do things that no one’s seen before, like panning at 200 miles an hour.

Nobu: I’m so excited and I’ll look forward to continue co-developing with Claudio and Dan. I’m very happy to do this. So much fun.

Congratulations. I look forward to the next excellent adventure of Claudio and Dan tormenting the Sony team to do something even smaller.

Claudio: You never know.