Sebastien Gonon, Cinematographer, wrote, “Lately I used Bausch & Lomb Super Baltars on an Alexa. I was quite happy with their soft look, pastely colors, producing nice flares and sharp when T Stop wasn’t opened too wide. They are soft, but not too much, which can be the case with uncoated lenses that can be way too flat.”

But, before you bring your pristine Master Primes, Summilux-C, and 5/i lenses to the friendly neighborhood sand-blaster — here’s a quick primer on lens coatings and what they do.

In “Camera Lenses, From Box Camera to Digital,” Gregory Hallock Smith writes that whenever you have a glass-to-air lens surface, the glass will pass most of the light through, but will reflect some of the light. These reflections can add up to a significant loss in transmitted light.

Few discussions of lens theory begin without a phone call to Iain Neil. He reminded me of the piece he wrote in the ASC Manual, “In the ‘old days’ (the first half of the 20th century) all lens designs, including cine ones, had to be kept simple, employing up to five lens elements…This was simply due to the fact that anti-reflection coatings did not exist.”

If a lens had 5 elements–that would be 10 refractive surfaces–each losing 5% of the light. A 5-element 50 mm f2.8 lens might lose more than 50% of the light, giving you a stop of T3.8. Now, consider that many modern cine primes and zooms have 20 or more elements.

So why the sudden interest in uncoated and vintage coated lenses?

Anti-reflection coatings were developed around 1936, and were used in cine lenses beginning around the mid 1940s. Before AR coatings were used, the lenses were simpler in design. Simply sand-blasting the coatings off modern lenses would be somewhat expensive, kind of irreversible, probably void your warranty, and most likely yield disappointing results. The image would be much “flatter,” “washed out,” not to mention having to contend with several stops of light loss. I would highly recommend Low-Con, Fog, Double Fog, Promist and Diffusion filters on the front of the lens instead.

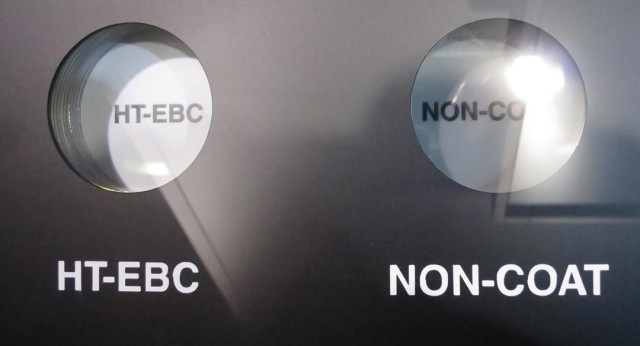

Coatings evolved, which is why vintage Super Baltars and original Cooke Panchros are very much in vogue. Each decade brought advancements in AR, with unique properties, contrast, color, ghosting, and “look.”

There are thousands of each brand of high-end digital cine camera. And each family has the same sensor. As Danys Bruyere said recently, “They all look very similar.” It’s not like having scores of different film stocks and emulsions, different labs, variables in processing, timing, and secret sauces. Sure, you can adjust the digital camera’s ISO, gamma curves, and menuable items. But how do you, as DP, differentiate your work from your dreaded rival? Lenses. New and Vintage. Also: filters, the mysteries of coatings, spherical or anamorphic, nets behind the lens. Aha.

And then, all of a sudden, the next big thing may be “the rediscovery” of the latest meticulously crafted, super-sharp, superbly anti-reflective, breathless, multi-coated, multi-element lenses. It’s Style.

Canon has a helpful page on lens coatings.

Image at top from the Fujifilm exhibit at Photokina 2012.

Maybe the public’s overuse of Instagram-style effects will eventually result in backlash, with a renewed appreciation of what the lensmaker’s art can deliver.